Over the past three years, I’ve interviewed some fascinating and accomplished people. I’ve learned much from each person. I’ve felt delighted to share their loves, laughs, trials and feats with Solvitur Ambulando readers through the edited transcripts of the conversations.

But look, podcasts reign supreme in the world. Over the past 10 years, people have become accustomed to engaging with the interview format through audio or video recordings of conversations. They have less interest in reading a lengthy transcript, even when edited for readability.

The time has come for me to, er, catch up to the times. Today, I launch the podcast companion to the written Solvitur Ambulando newsletter, “Walks of Life.”

The podcast will carry my interviews with these terrific writers, thinkers, artists and businesspeople. Each episode will include the audio interview and a lightly edited transcript. It will also include my analysis of the interview – what especially stood out to me, my key takeaways, and how the conversation has impacted me since it occurred. I hope my short after-action-analysis gets you as excited to listen to the interview as I was to converse with the interviewee.

Without further ado, let me introduce the first conversation of this podcast!

To paraphrase Mark Twain, the death of the physical book has been greatly exaggerated. Amid the two-decade assault by online writing and e-books, and the ascendancy of new media formats, the paper codex takes a lickin’ and keeps on tickin’. And yet, keen observers have pondered a malaise among book publishers. New books seem increasingly alike. Up-and-coming authors engaging in weighty research and analysis, like Ron Chernow, John McPhee and John Keegan, seem virtually non-existent because the new economics of publishing don’t allow for extended deep toil on a subject unless it’s absolutely guaranteed to become a hit.

In the next half-century, when we look back at book publishing, the name Ellen Fishbein and her company, Altamira Studio, will loom large. Currently frenemies with the legacy book publishers – not from ill will, but simply more attuned to the illnesses affecting the patient than the patient is – Ellen and Altamira are blazing a new trail for book publishing. From unique ways of marketing to the purposeful architecture of their books, Ellen and team love books, and want to create a publisher known for loving readers too. They also do excellent work as writing coaches.

In this fascinating talk, Ellen and I discuss in detail the dysfunctions of the book publishing industry; the future of online writing and associated businesses; her “personal bible” and what books it includes; and what she learned from studying with the Jesuits at Fordham University.

Some Points to Ponder

Ellen gives voice to the frustration I’ve felt for a couple years with Amazon. Its recommendations, well, suck. For all its logistical prowess and Prime Big Deal Days, Amazon has not been able to unlock for us a supremely human emotion: serendipity.

I truly enjoy writing Solvitur Ambulando and I relish reading many newsletters. And yet, and yet, reading them does not replace reading books. In a book, an author has spent months, maybe years or decades or a lifetime digging deep into a topic. There is something powerful about learning from a thinker who has wrestled, mulled over, mused, re-thought, and struggled with a topic for a long period of time. Even with authors of both books and newsletters, increasingly I find myself gravitating back toward the books. I’d rather read Martin Shaw’s books than his Substack. Ellen and I did not directly discuss this aspect of content consumption, but in reviewing our interview, this idea kept coming back to me.

What books do you read again and again and again? Why do you continue to invest time and energy in them? What did they teach you differently this year than five years ago? I explore that question with my annual reading of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. (2023, 2022 – two of the 28 years I have read it).) Ellen offers a beautiful answer as we talked about her “personal bible” and the 10 books she includes in it. Such a highlight of our talk.

Our conversation has prompted a lot of thinking around the ephemeral nature of modern yearnings contrasted with longings for permanence and immortality by our ancestors.

Very clearly, Ellen absorbed so many lessons from her philosophy classes in college. Those lessons come out in her answers and her approach to life and work. Her love for and learnings from poetry – beautiful, lyrical writing – also sing throughout this conversation. One of the age-old questions in Western philosophy is whether we as a civilization fundamentally side with the philosophers or the poets. Ellen makes me wonder whether we need to find a way to give them equal footing, and commensurate honor.

Again, I love love loved this talk with Ellen. Whether you listen to the audio, or read the transcript below, you will too! Thank you, Ellen!

Let's start with the basics, Ellen. I've known you for a while through a writing group we're a part of called Foster. But your main day job is helping to lead Altamira Studio. What is it and what are you trying to do?

Our business has two components: the Writing.coach service and Altamira Studio, our publishing branch. It began in late 2019 with just writing coaching. I started offering this service on a friend's advice, and it quickly took off. I immediately needed to build a team to meet demand, partly due to coinciding with COVID.

The writing coaching service primarily caters to people with business-related writing needs, including software company CEOs, investors, and entrepreneurs focused on writing. Through this business, we became involved in projects within the legacy publishing industry that produces mainstream books for retailers like Barnes & Noble. We learned a great deal about the book pipeline and the industry. It answered questions I'd had for years.

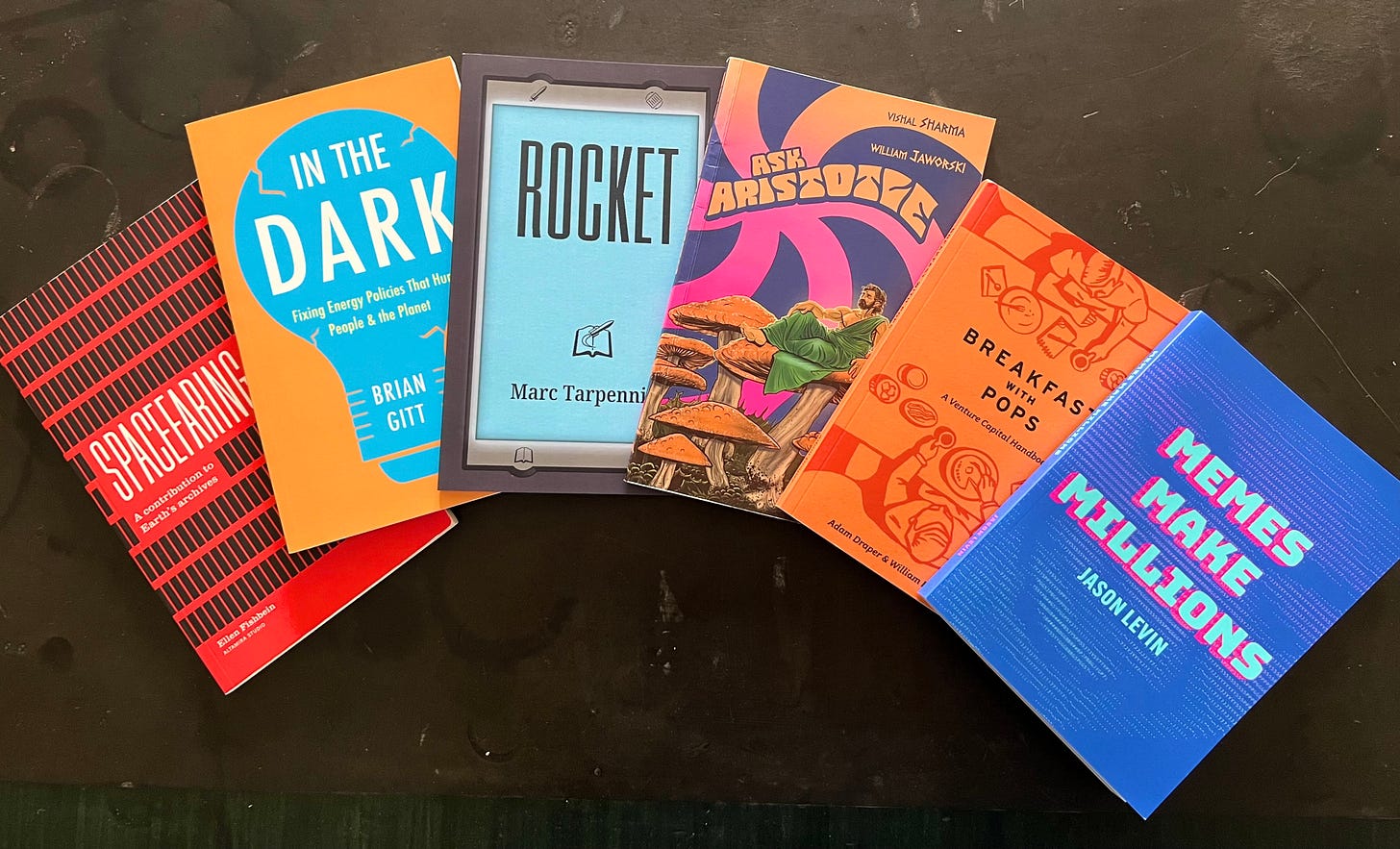

Given our position as a respected editorial team that had worked on several high-profile projects, we decided to start our own publishing experiment: Altamira Studio. It's an independent, highly experimental publishing company. We've produced six books for sale, experimented with a subscription model involving printing and publishing, and created an audiobook and some eBooks.

We're forging our own path within the larger publishing world, operating at the frontier of what might be possible in modern publishing. That's what Altamira Studio is.

You use the phrase “what might be possible at the frontier of publishing.” What are your hopes for the frontier? What do you think could be possible at the frontier?

There are some really basic, nuts and bolts, extremely ground-floor-level things covered by bureaucratic bloat in the industry. Let me step back to the origin story I like to share, which is true, but it took me a while to put the pieces together.

Growing up, reading was a huge thing for me. I was always reading – a huge bookworm. Books were really inspirational and important to me. Then somehow, 20-ish years passed, and I found myself feeling like I'd lost my love of reading. I'd walk into bookstores, look at all the new books, and typically walk out with nothing. Something similar happened with Amazon giving book recommendations. I'd consistently find that new books didn't interest me, or when I did get them, I wouldn't finish them. I'd get about 40 pages in and just get bored – especially with nonfiction.

This happened gradually over years. For a long time, I blamed myself. I thought, "I must've become a shitty person. I must've lost my attention span. I guess I've just been 'interneted' into not being interested in books anymore."

Eventually, as a result of insights from experiences with the publishing industry, I realized, "Oh, here's a sausage-making factory. No wonder I don't like these sausages. The factory's all messed up. All the machines are broken. All the processes are messed up. The distribution is messed up. The ingredients are a disaster. Everything's a mess."

Coming back to the question of what's possible at the frontier, a basic example is that publishing companies are locked into a minimum length of 300 pages for most books, or at least 250. They have these minimum word counts built into authors' contracts. It partly makes sense, because if you pay someone to write a book and they give you 2,000 words, that's not good. But the publishers’ minimum word counts are very high, often resulting in nonfiction authors adding fluff to books just to meet the publisher's word count. The publisher doesn't cut it; in fact, they encourage this fluff-adding.

I've had experiences where I've advised people on putting together an airtight 180-page book with nothing inessential and everything essential. Then it went to a legacy press, and a year and a half later, it came out 250 pages long. Looking at what they added, it's just all fluff. This is totally standard practice, partly due to the status quo and partly due to weird internal bureaucratic pricing models. They don't believe they can charge as much for a shorter book.

To me, that's ridiculous. Look at Common Sense by Thomas Paine – it's about 24,000 words, 100 pages, and it changed the world.

The next level up, in terms of frontiers, also speaks to the bureaucratic bloat, because of how publishing companies have collided with the internet without really adapting. What used to be distinct media – books, magazines, radio, TV – are now all ways of consuming information on the internet. The book market started to change, and publishers wondered how to continue selling 10,000 to 50,000 copies of a book. That’s how many they need to sell to avoid losing money.

They created a process based on social media followings. Authors who can build a big following on Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, or newsletters – as long as the numbers are big enough – are attractive to publishers. If you have 500,000 newsletter subscribers you can potentially push your book to, the publisher knows probably 20,000 of those people will buy the book.

The problem is, there's a whole skillset and a lot of overhead, money, time, and effort that goes into building such a following online. The people who are good at that, or more importantly, inclined to build a following of that scale, are very rarely the kind of people who really have a book to write.

You end up in this weird situation where publishers have a long roster of ghostwriters. The recipe is: find somebody with a big social media following and pair them up with a writer who's going to write the book. Sometimes that person gets paid pretty well, keeps the lights on for their family. But often they're generating the ideas and someone else is taking credit, or they're diluting the ideas. This collaboration is distorting the content and creating a pipeline of content that I think is generally inferior to what would happen if we got back to first principles and focused on people who are really good writers and whose stuff might resonate with readers.

Originally, I was very adversarial against the publishers and even the ghostwriters for this. I took a very combative stance, but I'm revising my stance somewhat. I think one of the biggest things that really needs to be fixed – and this goes to maybe the most complex part of the frontier thing – is Amazon and the book discovery world.

Amazon is doing a lot to push the same kind of book again and again to people and regress everything to the mean in ways that aren't serving authors, publishers, readers, or anybody in the whole thing. You're shaking your head. Yeah, it's a big mess.

Yeah. I can't remember the last time I bought a book on Amazon from their recommendations because of exactly the phenomenon you're talking about. Amazon recommends a ton of books that are 90% of the book I just read. When I'm looking up books on Amazon now, I put in weird search terms and I see what comes up. That usually gives me better suggestions than Amazon suggestions.

It's tough because Amazon owns Goodreads, which basically reinforces that same pattern they're doing on Amazon. Verbal recommendations from friends aren’t much better, because everybody's so connected to the internet. There's so much homogenization of what people are getting served up to them because of how the internet works.

That's the furthest – maybe the most abstract and complex – problem on the frontier of publishing. Even beyond that, there's AI, which is interesting as well. I actually have a number of friends in publishing, and I told one of them what ChatGPT was when it was going viral. They hadn’t even heard of it! And really, they should really be with the program on AI.

Do you think AI is going to take over book writing? It's like my daughter taking tennis lessons. I give it a year until she can beat me and my wife. She's just getting that good, that fast. How soon until AI can write a novel that you and I can't tell wasn't written by a human being?

There is a fiction–nonfiction divide there. In certain ways, I think AI will be better at "independently" writing fiction, but only according to very strict formulas. If you look at all those pulp sci-fi and mystery novels, I'm pretty sure that similar to how Midjourney can generate images that look so much like DeviantArt images, it's analogous. If you feed in all these pulp mystery, sci-fi, and true crime type of writing, I think AI is going to get really good at matching that pattern and swapping the names, mysteries, and names of planets, and so on.

With nonfiction, there's a really interesting opportunity. What we have found so far – and I'm putting out an article about this in the next few days – is that LLMs are not as good at the nonfiction book architecture process. Let's say you have a subject matter expert, like a rocket scientist, and you're trying to work with that person to put a book together. My team and I have done this a bunch of times, helping people take their subject matter expertise and systematize the idea, put it into the orderg in which it should be encountered and understood in a book by a reader. We call it book blueprinting.

We've done experiments with AI where we've tried to get an LLM to do that job, where it interviews a subject matter expert, or at least takes inputs from them and turns that into an actual functional book architecture that can be followed. It doesn't seem to be so good at that task, because there's a relevance filtering issue. In a nutshell, when people talk about their area of expertise, they'll say a bunch of stuff. Some of it is redundant, some is irrelevant, and the LLMs don't seem to be catching up very quickly. They're a little too agreeable; they kind of accept everything.

We're very interested in talking to people who want to experiment further and train some models in more sophisticated ways around that. There's a big opportunity to take that blueprinting architectural skillset and take subject matter experts who might have never written a book otherwise, use the transcription of what they say about their subject matter, engage in that relevance filtering exercise, and produce some really interesting books. It does shorten the amount of hands-at-the-keyboard time it actually takes to get people's expertise down. Does that make sense?

It does. As you were talking, I had in mind Tommy Caldwell's book, The Push. He’s the guy who free soloed The Dawn Wall on El Capitan in Yosemite. I read the book, which had a ghostwriter named Kelly Cordes. I kept thinking about The Autobiography of Malcolm X as told to Alex Haley. Malcolm X would go to Alex Haley's apartment at 2:00 in the morning, crash on his couch, and then riff for the next four hours. Alex Haley would record it, digest that, and then the next time Malcolm X came over, they'd talk about it and he'd riff some more.

With Alex Haley, you got one of the great autobiographies of the 20th century. Tommy Caldwell's was good, but there was something weird where there was too much filtering – and not enough filtering, if that makes sense. There was so much Tommy Caldwell that it almost seemed unreal, and in another sense, there was too little of him. It was too polished, too ghostwritten, and that kind of turned me off too. Anyway, that dichotomy between those two books kept coming to mind as you were talking.

There's a place for books that are more heavily transcription-based than that, because what happens there is there's too much hands-at-the-keyboard ghostwriting where somebody's changing how somebody talks and just straight-up making stuff up.

I think a better process, which we've already applied to create some drafts in production that are going to be pretty awesome, is where we create a very detailed step-by-step blueprint outline of the book. Then we get together for an intensive, three days with somebody. We ask each of our questions from the blueprint, and we have the writer speak to each point. Then we transcribe all those paragraphs and put them where they belong.

Then the only kind of "ghostwriting" is writing connecting sentences. Because we've so meticulously mapped out what we want to say, we're just giving them a container and saying, "Okay, pour that substance into this container." And then, "Okay, here's the next one. Here's the next one. Here's the next one." But you have to have the right process.

Honestly, this is my co-founder Bill Jaworski’s superpower. I asked him, "Do you think you could teach me how to be as good at this as you are at this book blueprinting job? Being able to exactly identify what these containers are? This ability to hold the architecture of a book in your head?" He replied, "It would take a long time." He's really, really good at it. He's very skilled at it. He advised on a lot of dissertations, he's advised on a lot of books, he's written a bunch of books. So it's a talent as well as a practiced skill.

You have to have that human component. Then the AI component is more of a transcription and cleanup job. That could be an interesting category of books where that El Capitan book could have been done better if they’d had better architects involved. That's how I see it.

I want to go back for a moment. You keep saying “we,” and then you just mentioned your co-founder, Bill. Tell us about the team at Altamira Studio.

One of them is actually my partner in life as well as business. We've been together for a very long time. We met online dating back in 2011 and we've been together ever since. His name is Sam. We moved to Texas from New York, thinking we were going to start a business together. It ended up taking us a long time to figure out how to do that. He was previously at Palantir, which is a big software company that's involved in AI. At some point, he was done being at Palantir - it was very high pressure and crazy. He wanted to do something else and I wanted to be involved in entrepreneurship.

We ended up coming to Texas with these vague notions of entrepreneurship. It took a long time before this writing coaching opportunity emerged. The first person I really needed to call was actually not Sam, but Bill. Bill was a professor at Fordham University where I got my bachelor's degree. We met in New York when he was teaching analytic philosophy and symbolic logic. He got up in front of a group of about 120 students and basically said, "Most academic writing is terrible writing. It's really bad. We're not going to do any of that in this class. We're going to prioritize clarity." I knew at that moment that he wasn't long for the world of academia. I just knew. This was my freshman year, a couple of weeks before I incorporated my first company, which was also an editing and writing business.

That was around 2013. I kept in touch with him for years after I graduated. Circa 2018, he was having thoughts of leaving academia. In 2019, we started working together on these writing coaching projects. Now we've been doing this together for years. We've got a bunch of bestsellers under our belt and we started this publishing company.

His expertise is really phenomenal in terms of knowing the architecture of a great book, having this ridiculously rigorous, logical approach to mapping out concepts. Sam has been tremendously helpful as well. The three of us started this effort and became equal co-founders.

Sam is going to be moving on to doing something else full-time. This was always the plan - Sam wanted to go in a direction involving film and fixing some of the same problems in the film and cinema world that I wanted to fix in the book world. If you talk to movie buffs - maybe you are one, I don't know that about you - but if you talk to movie buffs, they have a lot of the same comments that I was having about books. They watch all the new movies and they complain, "This stuff is so cookie-cutter. Why don't we have anything like The Matrix or Pulp Fiction anymore?"

You're nodding. You know what I'm talking about?

Yeah, absolutely.

Now there's a big opportunity involving AI and film and visual AI. And Sam, as an engineer who really knows computers, AI and film, is perfectly suited to be in that space.

He continues to be a co-owner of the business. He did some really important things, including underwriting the very early unstable phases of our work. "Hey, I got your back if you miss payroll." That kind of stuff. Also setting up a lot of technology and processes for us. And helping us work through our initial strategy.

Ultimately his heart is in the cinema and TV world. So, he's going in that direction. Bill and I are continuing to be full-time on Writing Coach and Altamira Studio. All of us are very unified in this cultural mission around making a difference. We have a lot of optimism around cultural assets.

We have other people who are really important to the business. A few contractors who we work with are really important. An illustrator who is incredible and who did a bunch of the cover illustrations. We have a very savvy social media guy who found me because he was looking for a writing coach for his self-published book. And now I pay him to work with me on social media and staying organized and all that kind of stuff.

We have a print shop that we found after calling a bunch of places. And so, these various pieces have all come together over the years as necessity has brought them into the fold.

That's awesome. Let me go back to our conversation about publishing. I want to look at publishing in a few different ways. You and I share a skepticism about what's called the production economy – the sheer number of products out there. How many travel blazers do we need to sell on Huckberry, people? We see it with intellectual assets, too. Think of online platforms like Substack. I'm on it, somewhat reluctantly. I don't hate it, but I don't love it. But it basically exists as a tool for blasting more email out to people – constantly sending more and more emails out there to people. Do people really need more emails in their lives? Dig into your critique of the production economy.

Yeah, so my point of view upsets a lot of people, but it's hard for me to not hold this point of view. I think that the dogma or the message that “if you're a creative person, if you're a writer, in this day and age, then your art form is emails” - you should be focused on writing the best emails and getting all these people to buy access to your emails – I think that's a very unimaginative, very cynical fad. I don't think that's something that's going to stand the test of time.

Now, I'm not a technophobe at all. I think all these platforms are really interesting, including Substack. They all have a place in the evolution of things. After I came to Texas, I worked for about three years at a consumer media company comparable to Business Insider. I was hired to be an editor. And there was a 700 article per month quota. That is actually truly insane. We had about 20 writers and that quota meant every writer publishing more than one article per day.

We also knew that there was this crazy power law or tail-of-the-dragon effect. One of those 700 articles was actually driving 80% of the traffic for the month. That one article was keeping the lights on.

I showed up and saw this situation. I didn't even get hired full time at first. I was on a contract getting $2,500 a month. And I said, "This is not how we're going to run things." Because writers were just taking a YouTube video that was going viral, putting a headline and three sentences on it, and embedding the video in an article. And that would actually work, which is ridiculous, right?

We had this incredibly low-quality content. We had a two-person editorial team that had to read all these articles. We would go home and our heads would hurt. I went to the CEO, who was, to his credit, incredibly receptive to me being extremely unfiltered about the whole thing. I told him, "This 700 article quota is completely insane. You have to look at the audience and think about what they're interested in. We could do 100 articles a month, which is still a lot. We can publish three times a day. We can have an article in the morning, an article at lunch, and an article in the evening. Each of the 20 writers can write about five articles a month."

I said, "We're going to look at what the audience has responded to." Fortunately, the website had been operational for a little while. It was a small number of topics. There were clear patterns that you could identify even from the crap that they had been publishing.

I said, "OK, we're going to try this for the next quarter." The publication was related to the outdoors – hunting, fishing, hiking, National Parks and so on. I said, "It's fall. It's deer season. We're going to do all these deer articles. And here's a good blueprint for the kind of deer articles we're going to do."

Within a couple months, everyone at the company was saying I had changed the whole company, which was really nice. We went down to a sane quota. When I came in, the editorial team was working seven days a week. It was completely insane. We took it down. Traffic didn't suffer at all from going from 700 articles to 100 articles. As a matter of fact, traffic did fine and even better than before on many days. And it kept growing.

That was the first clue I had that there was some misguided behavior in this world where content is technically free. It doesn't cost money to put the article on the website. Not in the concrete way it costs money to put an article on a piece of paper. This was my first clue that something was not quite right in that whole mindset.

I think that the dogma around a lot of the Substack and similar writing mirrors what that company was doing when I showed up. There's a lot of "do more and more and more, ship more and more, screw quality, go for volume." I think that is a fad. People are wising up to that. Now that approach is more undifferentiated from AI than anything else.

Let me mention something else. And I really don't want this to be misunderstood because I don't have any ill will toward these people whatsoever. In fact, I think they've done some really great things. There's another writing company that has recently and famously announced they’re doing their last writing cohort ever, then they are shutting down. I'm friends with the CEO. We know each other really well. That company started around the same time as mine.

Their original idea was "We have a five-week writing boot camp where we're gonna write five articles in five weeks." At the same time, I was doing a six-week writing coaching program where I was saying, "Write one article with me over six weeks." And so, people would constantly come to me and go, "Why would I come to you and get one article in six weeks when I can go to that guy and get five articles in five weeks?" And I replied, "Because we're going to do something that you're really proud of. We're going to do something that's high quality. We're going to do something that's gonna have a shelf life. It's going to stand the test of time. It's gonna differentiate you. If that doesn't make sense to you, then you should probably go to that guy."

I had a lot of people not work with me because they decided to do the other writing approach. But two years into that program, the other company changed their approach. When AI started to get big, they changed to a program of writing one core article over five weeks. My response was, "That's what I've been doing the whole time."

Except by the time they got there, I was already somewhere further. We had been producing physical books for months by then. We figured out how to create books because it was the next step. When you've realized that one good article is better than five crappy ones, one good book that stands the test of time is better than online articles. We were already moving in this analog direction – "Write one book."

We worked Brian Gitt, who works in business development in the nuclear energy space. He wrote a short book with us. And he has used it to get speaking engagements and podcast appearances and a lot of recognition. And writing with us helped him land a really great job in exactly the space that he wanted to be in. Before he had the book, he was writing articles at a very slow pace. But he was really betting on quality. And in particular, he was really hammering home one core idea, one high-quality thing. And he had been working with us since 2020.

And so, I think that all that stuff is very much a fad. I think AI now makes it even less relevant in terms of staying power than it ever was. I think it's just not a good use of time. What are your thoughts?

As you were talking, I went up and I got my handy copy of Thucydides from my bookshelf. Thucydides wrote one book, after he was ousted as a general of the Athenians. It took him an enormous amount of time and effort and thought to write that book. It takes the reader an enormous amount of time and thought and effort to digest that book. Today, it is not that hard to publish something. But it's actually a non-trivial amount of effort to digest it, for a reader even to determine whether to continue reading. That production versus consumer effort and time imbalance is a real danger for consumers, for readers. I have to read this from Book I of Thucydides. “The absence of romance in my history will, I fear, distract somewhat from its interest. But if it be judged useful by those inquirers who desire an exact knowledge of the past as an aid to the understanding of the future, which in the course of human things, must resemble if it does not reflect it, I shall be content. In fine, I have written my work, not as an essay which is to win the applause of the moment, but as a possession for all time.” How many people today are writing something for all time?

“A possession for all time,” yes. Altamira Studio – we picked that because of the caves of Altamira, which I'm sure you're familiar with, in northern Spain. I really want to go there on a weird business pilgrimage. The caves contain gorgeous paintings from 20,000 years before writing was invented.

Those paintings were created for the people around the caves – and also to stand the test of time. The fact that they're still there from these cave-dwelling, tiny tribes from 25,000 years ago, says so much about our shared humanity.

The internet and the last 10 years of "best practices" – the idea that we know what the "best practices" are with something that was invented in the last few decades. On this grand timeline of human history, it's completely brand new. No idea. We're still totally at the beginning of learning how to use these tools.

People think, "The best practice is to do high-volume writing." I think that's a trap. And I think it's very cynical to treat the creative spirit in that way.

Let me keep going with the theme of slowing down and different publishing modes. You’ve begun experimenting with good old-fashioned snail mail, actually sending items to people through the mail. It's called Muse by Mail. Tell us a little bit about it and tell us why you're embracing slow communication, slow mail.

We've just shipped out the first one. So it’s still experimental, like a lot of things at Altamira. This kind of goes back to the problems with Amazon and book discovery and content curation that you and I were talking about.

In your questions that you sent me before the call, you asked about what the next 20 years in book publishing will look like. It's already been proven that there's going to be an analog book market that is not going to get deleted by all the digital options. It can get changed, but there are people who like physical books. In fact, there are a lot of people who are digitally native and who still like physical books very much. That's going to continue to be a thing. But there are opportunities to shape it in new and different and interesting ways.

Again, we have a book discovery / reading material discovery issue. It's a burden on readers to find new things coming out. That's part of why you have these massive marketing machines that publishers and authors are building for each individual book.

People have said this to me and I feel really proud to repeat it - if Altamira published a book, chances are you will find it valuable. We are starting to have a brand that has earned the trust of readers. We are so anti-fluff – readers know we will not waste their time. And we are interested in presenting them with something that might be off the beaten path and that would appeal to them.

So the concept of Muse by Mail is that every quarter, every season, I'm going to send you a package. What's in the package? It’ll have a pocket inspiration book – called The Muse and edited by me. It’s all about creative topics - fiction and nonfiction. This one includes a nonfiction piece called “The Forbidden Course” and a fiction one called “The Messenger.” And it includes seven writing prompts from me. It’s an inspirational, cool, creative thing, from me.

You will also receive a book – curated for you by me. Maybe a book we published, maybe not. Right now, I'm having a good time with the fact that this is not at scale. For example, I sent a subscriber a copy of Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 because he hadn't read anything by Ray Bradbury. He was interested in classic sci-fi and I knew he had to read it. You just have to.

Over time it's probably going to get streamlined into people receiving one of the two latest things that we think are interesting. And always also getting The Muse.

So far so good. The 30-ish people who are subscribing to Muse by Mail are really into it. Again, it takes the burden of content discovery off of them. They know the items we send will be well-chosen and inspirational.

Over time, I'm also hoping our strong connection with readers will get us to a virtuous cycle. They give us great feedback and we use that to deliver books that delight them.

Why physical items? Why am I attracted to that? Just today, there’s a change going viral about a big lawsuit concerning Internet Archive. Some publishers have some copyright issues and are trying to delete 500,000 books from the digital lending library. The trouble is, many of these books on Internet Archive – which has 500,000 books – are out of print. You can’t find them anywhere else. So you see how ephemeral the digital world is. Things can get changed, things can get deleted.

There's a permanence to the analog format that is really not symbolic, but really powerful.

You can take my physical book from me when you pry it from my cold, dead hands.

Exactly, exactly. It's a cold, dead hands thing. And something else. I will read on my phone, but it is really nice to have a single-purpose object – one that is not also calling to you to answer various messages and get on the internet and do all sorts of other stuff. I think there's going to continue to be interest in single-use objects, like a physical book. I have an interest in that.

Finally, we have an amazing connection with an American print shop that does all its manufacturing 35 minutes away from where I live. We love their work. We love showcasing their work.

That is awesome. Let me go back. You mentioned briefly your prognosis for the next 20 years of book publishing. Talk to us also about the next 20 years of online publishing. You already mentioned a massive shift in emphasis from another online coaching / content creation company. What's the next 20 years of online publishing look like? Will Substack reign supreme? Will 9 out of 10 creators go away because they can't make a living?

It's a really good question. One place I landed – the book format will continue to be a format that people are into.

As far as online publishing, articles and content, I think that two-way networks like Twitter and TikTok and YouTube – where you can post items and people can comment and have dialogue – are here to stay. The idea of people being able to talk to each other with all these other people who are also online on the same platform is ridiculously powerful.

With online publications, you've seen some really successful people, like Ben Thompson and Lenny Rachitsky, who have taken a lot of eyeballs away from legacy publications like The New York Times and The Atlantic. A lot of people will go and read their newsletters or other solo writer. They're opting to engage with them over institutional journal-type media. As a source of red hot information – and maybe better than you might get from the “mainstream” – I think that pattern will probably continue.

But I also think that, by and large, those people will not be monetizing their writing exclusively. I think that especially over the long term. In the near term, it's less clear. Over the long term, this idea of subscriptions and you're going to only write and people will pay you for your blog posts and that's your business – I don't really think that will last.

More likely, it’ll be like Paul Graham, the Y Combinator founder. He writes and has written a ton of essays. All of it is in service of attracting attention to Y Combinator. That’s how he actually makes money. In the book world, a lot of best-selling authors, for example Nir Eyal, who wrote Hooked, don’t make their money off of book sales. Even though he's done a lot of book sales, he probably makes more money off of speaking engagements.

This idea of making money as an online writer blogging is tricky. Some people will make money writing in service of business ventures, either their own or for their employers. Companies will continue to put out writing. Public companies will continue to put out articles and reports to manage their stock prices. There will be jobs for writers for quite some time.

People will do what I do – I write free articles, then people work with me as their coach. That’s how I make money. That will be a continuing trend. But the idea of monetizing the writing specifically – I'm not sure about that. There are opportunities for writers to write for all the media – TV and movies and speeches.

The number of writers who will do the Lenny Rachitsky thing – will be a very small number of people. Most of whom have already done it. Even he has other components to his business model. More people will monetize online communities or courses, coaching, other virtual products or services. Or retreats, shows and performances. Things like that.

So that's what I think. I don't really think that that archetype of a writer who's making money only on blog posts and newsletters is a real thing.

This is awesome insight, Ellen. I want to ask a few questions about your personal approach to life. For instance, you have shared your notion of a “personal Bible.” What is that? What's included in your personal Bible and why?

I'm super grateful for that question because back when I was working at that consumer media company, I realized I was not long for that company. Not because of any ill will, but just because I'm ultimately unemployable on some level. I realized that.

I started participating in a forum that Shane Parrish started, the Farnam Street Learning Community. This was around 2018. At that time, there were around 1,000 people – all people who were interested in books and reading. And I thought, this is cool, super cool. I'm an editor at this weird media company and I'm going to eventually move on to doing other things. So, I better check these people out.

At the time, I had some downtime at the office every day. So, I was posting stuff on this Farnam Street Learning Community. I decided to challenge myself to start some forum topics and see what people got excited about.

The topic of books people re-read kept coming up. So, I started a conversation about books that are like the Bible. People who are very religious, they'll read and reread and reread the Bible or any of the sacred texts. So I wrote a post called, "Have you found your Bible?" And I said, there are people who have pointed to a book they've read and reread, and that they love as much as scripture. For example, at his funeral Steve Jobs gave everybody copies of Autobiography of a Yogi.

Yeah, great book.

Great book. And I've noticed that a lot. Bob Dylan had that with Jack Kerouac. There were other examples. And, I have my own. I came up with four books that I had read multiple times that were biblical for me. And this was a viral post. People loved it. Over time it became something that people would ask me about. It's really funny.

Because you are curious about it, I decided to revise the Bible. I made it 10 books.

Wait, wait, are we hearing this first on this newsletter? Are we hearing this?

This is the very first time I'm sharing this.

Breaking news, everybody. Breaking news, Ellen's new Bible. Let's hear it.

I'm cracking up.

This is so great.

These are 10 books that I have read and reread quite a few times. I’ll share a one sentence explanation of why I'm so into it.

Oh, this makes my day.

The first one on the list is Brave New World by Aldous Huxley. The reason I love it so much is that what this book taught me about writing and life is that Shakespeare really matters. Shakespeare is absolutely super powerful. Brave New World was my gateway drug to reading Shakespeare. And the book itself is absolutely brilliant. The way that Aldous Huxley shows his devotion to Shakespeare is really one of a kind. Love, love that.

The second book on the list is Shakespeare's Sonnets. I've read and reread Shakespeare's Sonnets a million times, all of them. The big lesson that I learned from them was that Shakespeare put in the reps. You can see him learning how to write and getting better by wrestling with the sonnet constraint. If you read the Sonnets, you start to understand it as the training ground or the whetstone for his writing skills. It's fascinating to see how he's teaching himself how to write by dealing with this constraint of the sonnet form.

Third book on my list is Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand. What that taught me is that success in terms of writing, what is going to be successful, what kind of book is going to be successful can surprise the author – and everyone. It can be very unexpected. There's a lot of things I have to say about Atlas Shrugged and about Ayn Rand in general, which are all super controversial and polarizing.

The fourth one on the list is Metaphors We Live By. Incredible book. And what I learned from it was that language is metaphor. The book completely changes your paradigm on writing and it's amazing.

Fifth book is Zero to One by Peter Thiel. That book taught me that business writing is actually an art form in itself and can be really beautiful and timeless and doesn't have to be whitewashed and crappy the way that it normally is.

The sixth book is one I know you love a lot, The Glass Bead Game. Love that book very, very much. I've read it many times.

It's a great book.

I've read it many times. I go back to it when I'm lost. What that book taught me about writing is that people are smart. The fact that the book has had as much uptake as it has, and the fact that he actually won the Nobel Prize for it... the book is super complicated and very abstract and crazy, but it is beloved by many people. It's a reminder to not underestimate people. If a book like that can surface the way it did, then there's hope for pretty much anything, I think.

Next – Five Dialogues by Plato. I have a particular collection of five of the dialogues, especially Plato's Apology and a couple other dialogues that I've read a million times. That's where I learned about the idea of peaceful disagreeableness. You can be non-combative and you can challenge the status quo. The whole Socratic thing is incredibly valuable. That's biblical for me.

The eighth book is a collection of William Butler Yeats poems that I really love. Pretty much any collection I think counts, but basically all of his poems. I'm obsessed with William Butler Yeats. I think he's incredible. After Shakespeare, and Bob Dylan, he's my favorite poet. He's really great. And what I learned about writing from him was that it's a long game. My edition of this book has the dates of when all the poems were written. You see a very slow evolution of William Butler Yeats learning one thing at a time and getting better. When he was in his 50s, he wrote a lot of his very best stuff. When you compare that to some of his earlier stuff, you see what happens when you do this day in and day out. He even refers to the practice of writing as an "accustomed toil," which I love. That's totally right. It’s a long game. Whenever I start to get impatient, I go to Yeats.

The ninth book on the list is the screenplay for this movie, Network, which Paddy Chayefsky wrote. I think Paddy Chayefsky is the only person who's won best writer three times without a co-writer – something like that. He's really great at screenwriting. In particular, the screenplay for Network is totally genius. It's got some monologues that are on Shakespeare's level, to my mind. So, what I learned is, you can still do something that's as good as a Shakespearean monologue in more modern dramatic English. That’s great – I love that.

The last one is the Tao Te Ching, which I have read many times in many translations. I took many lessons from it. One was the idea of letting the rivers flow into you. There's a metaphor in one of the Tao Te Ching’s chapters: the ocean is the master of all the waterways, because all the rivers flow into the ocean. There's something very profound about this idea of placing yourself beneath the rivers and letting them flow into you. I'm not sure exactly what that means, but it means something very profound about writing and life.

Yeah, that's amazing. That is an amazing list of books, Ellen. I've got to ask you a question about #7, Plato’s Dialogues, specifically The Apology. Here's my question: do you agree with Plato and the philosophers or do you agree with the poets? Plato using Socrates is basically accusing the poets of lying. And the poets are saying, put Socrates to death - he’s the one damaging the place. Who do you agree with?

I have to side with Socrates. I think that there are a lot of people who can be lyrical and who can be poetic, but can still be wrong. There are a lot of times when people simply want to avoid the truth. It's painful to be challenged. It's painful to have people's fakery challenged. We have a lot of people now who are like the Sophists of that time period. We have a lot of people who are ruining everything by teaching stuff that doesn't help anybody.

So yeah, I have to side with Socrates. At the end of the day, I think that's part of why I picked a philosopher as my co-founder. Being able to take a stand for what is fundamentally philosophically right and being able to stand for the truth supersedes pretty much everything.

Nice. I love this list. It includes books I know and love, and books I disagree with, and ones I haven’t read and want to read now. I love this list. This is awesome.

I figured it might be a little spicy.

Oh, it's so good. I love it. I have a couple of points of curiosity.

I'm ready.

How do you think about bringing beauty and nobility into your life?

It's interesting. One of the things I'm really grateful for is Sam. Even though he has an engineering and technology background, in many ways, he's an artist at heart, even more so than I am. And I am definitely an artist, in terms of writing poetry and all this kind of stuff. He has a sense for beauty being an end in itself. He has a deeper connection to that idea than I even normally have in my day-to-day life.

I have a little bit of a pragmatic, business-minded, day-to-day posture. Sam sees the world and he emphasizes truth and beauty. He says, civilization could collapse just because people stop telling each other true, beautiful stories. And he's totally right about that.

Having people in your life who have an internal compass oriented toward beauty on a fundamental level is really good. That compass is very strong. When my own internal compass is going haywire and getting distracted, Sam and other artists in my life are able to clear that away. They remind me that what actually matters is beauty. That this is worth doing because of a kind of reverence for beauty.

I actually count on people around me who have a really strong orientation toward beauty. I think we have those people who are born like that among us, right? A friend of mine is very business-minded and his wife is very much the artist in the relationship. We talked about that – what if we could protect and serve our artists better?

Also – you are a contributor to this answer – a lot of people in my life take a lot of walks.

Yeah, totally.

The people I know who religiously take a walk every day are some of the most creative and wonderful people. When I'm in the practice of walking, it helps a lot. I live in a place with beautiful trees and animals and stuff. That is very nice.

Seeing six baby birds all fly out of the nest at the same time – as cliche as it sounds, putting yourself in situations where you will encounter small, beautiful things. It’s not a matter of bringing it into your life. It’s theer’s It’s a matter of showing up for it.

I'm curious about your answer to that question about beauty in life.

My family is a big answer. My daughters and my wife. The growth of something beyond me is really beautiful. When you were talking about Metaphors We Live By, I find language beautiful. I'll read a story or a novel and I’ll encounter a brilliant, beautiful way of constructing language.

I listen to a podcast, The Emerald by Josh Schrei. He is such a beautiful storyteller – interweaving different modes of communication – music, singing, incantation, the inflection of his voice. It all reinforces what he's trying to get at. I find that fascinating.

Nature, too.

I find my office beautiful. I've constructed this space the way I want it. That beauty reflects back to me. I love my picture of Wendell Berry thinking. I love my cacti and my bonsai here. I’ve got my crazy cactus office jungle here. I get so much joy from it. I find it beautiful. And I’m trying to contribute to its beautiful growth. I love my totally goofball, Lego Zodiac figures that I put together every February.

Maybe it’s weird – because I was born with this heart problem, I find beauty in a lot of things. I find beauty in something almost every day.

I find beauty in all these things. Sometimes I simply look up. Or in my daily cup of tea, I find beauty in that ritual. I find it beautiful that long ago, a human thought, “I'm going to steep this leaf in hot water and see what happens.” And another human then created a beautiful ritual and ceremony around steeping that leaf. I find that really wondrous and amazing and beautiful.

I totally love that. I have a friend named Cam who is like that too. I asked him if he meditated. He's said, no, but I do another thing that's very reminiscent of what you described. I love that.

I find not giving up beautiful. Like a lot of cities right now, in Louisville, there's a real struggle with homelessness – with finding adequate housing for people who are on the fringe of society and really struggling. I find it beautiful that there is a non-trivial portion of our population that is willing to dedicate themselves to trying to solve that problem for other humans. That’s a really special, beautiful thing.

Appreciating people who are taking initiative to do good things for other people. That's one of the best things that can happen. A hundred percent.

Let me ask you a couple of last questions, Ellen.

Yeah.

Back on Altamira Studio: When somebody comes to you and says, “hey Ellen, I have a great book idea.” What filters do you put up? What screens do you put up? Is it the famous venture capital screens where you really care more about the person than the idea? Or is it more nuanced than that?

I thought about this and I talked to Bill about it too. If we meet somebody who wants to write a book, we want them to tell us what's on their mind. We both kind of have an attitude of openness to anybody who feels like they are being pulled in the direction of writing a book. We start openly. Then typically people will say a few things and we can hear that there's like a book thing in there or there's not.

It's really hard to pin down what the characteristics are. But it has something to do with the depth of the potential implications of the idea.

Someone recently came our way with a book idea. I was really unsure at first. Bill and I kind of both started asking questions. As it turned out, there is something there. But a lot of times when people talk about their idea, they don't have the perspective to exactly identify where the book is. It's a strange thing that way, actually for both fiction and nonfiction.

If we find that we think has a book in it – that someone could read in a 100 to 200 page format – and it would potentially cause them to restructure some element of their life or their worldview, or the way in which they think, feel, or change some aspect of life – we pay attention. If you think about it – how many conversations have you had where someone's actually changed your mind? It's rare, right?

With fiction, we're still trying to figure out how to publish fiction, honestly. Fiction, I'm looking for someone who has the fundamentals of dramatic structure figured out. That's very, very rare. With nonfiction, again, it's determining whether this person has something to say that would cause anybody to live their life differently moving forward. Is there a transformative experience somewhere in there?

The person I was talking about was saying there needs to be a new management style for this new day and age. And I can’t think of anything less interesting than that. Then we started to uncover what he was actually talking about. He was actually talking about a way to have a team of people, with every single person able to do deep work. Every person has to be able to focus in a safe way on the pursuit of their craft.

We started to go deeper and we saw some powerful anecdotes here. The guy has stories and experiences that coalesce around an idea that could lead people to change something about how they see the world, how they operate, and act differently.

That's not a very concrete answer, but we talked about it as a team. We tried to find a concrete answer. We landed with the notion that we’re willing to listen with wonder about whether a book is inside that idea. Would someone change because of reading that idea in a book format. Does that make sense?

It does. It's a beautiful answer. And I think it relates back to the 10 books in your Bible. As you were going through your one liners, I was taking a few notes. As you were just speaking, I was looking back on my notes. So much of what you said, you were reflecting to me how the book changed your worldview or your actions.

Shakespeare's Sonnets – putting in the reps. That book helped you see the importance of you putting in the reps. The Tao Te Ching, the letting the rivers flow into you – you don't exactly understand what that means in your world, but you know that it's a poetic thing. The words influenced you, that image has influenced you, in a profound way.

We talked earlier about fleeting, ephemeral (by the way, one of my favorite words) online writing. The books you talked about have changed generations and will change generations. They contain profound distillations of reality and lessons about truth. So much of online writing is groping, seeking, and not in an elegant way. It doesn't even have much to teach the writer. Not literally nothing, but it's online diary writing. That’s fine, but don't elevate it beyond its real station in the world.

Diary writing / casual conversations with people online. We have this concept on our team called rehearsing. Anytime you're talking with anybody about some of your ideas and anytime you're drafting something, that's a rehearsal. And this is a rehearsal for which I'm very grateful.

Definitely.

People appreciate being able to get on a podcast, because they like to rehearse what they're trying to say. And we help writers do that – through conversation and through writing. Social media and online publishing are good opportunities for rehearsal.

All right, last question for you. We've talked a lot about what you've learned – business, publishing, writing, and books. You went to a great Jesuit institution of America, Fordham University in New York. I also attended a great Jesuit university, Georgetown University in Washington, DC. What did you learn from the Jesuits? What did you learn from it being a Jesuit school that was a unique contribution to your learning? Except that Bill was not long for academia?

First of all, if he fit in anywhere, it was within the Jesuit setting. He is a rigorous political philosopher. Compared to other universities, the philosophy department at Fordham is huge. So, there's something to be said for the fact that meeting Bill there was actually very fortuitous.

The opportunity to take that much philosophy and also, I would say the opportunity to take that much philosophy as part of my degree, which was not in philosophy, definitely stands out. I took a philosophy class in high school. Everybody who took it had a great time and really liked it. Philosophy is this guilty pleasure. Most people who did it in college, maybe they took one philosophy course. I took something like four of them, you know? And theology too – I overlap them a bit.

I think it is really cool that it was built so I didn't have to feel like it was a guilty pleasure. It was required and that was cool. It was a setting with more room for reflection than the typical four-year degree is supposed to allow.

That was really huge for me. Like the fact that philosophy was not only allowed and available, but required. There was so much robust infrastructure for it. The logic courses were ridiculously valuable to me. To this day, a huge amount of what I do is asking people about premises. About counter arguments.

It’s incredibly valuable. It would be cool if more universities took that stance instead of treating it like a guilty pleasure. I do think there was a lot of value. Some of the most valuable stuff that I learned was definitely in the philosophy department.

That's awesome.

Do you feel that way?

So much of what you said resonated. I studied political philosophy. I started out in the School of Foreign Service and then I realized I like the theory of politics more than the reality of politics.

Oh, I did not know that about you, but that makes perfect sense.

I took enough classes to like minor in philosophy, theology, Spanish, English, Shakespeare, history, English. I was just too lazy to fill out the paperwork. I loved it, you know? I got my teeth kicked in by logic. It was so hard.

It's very hard, but it's really good.

I loved the presence of the Jesuits. A number of my friends later became Jesuits. That was really special. I attended some of their ceremonies, which was very moving. Georgetown’s motto is Utraque Unum – “both are one.” There are different meanings, but one is traditionally understood as: faith and reason are one. Georgetown was the first place that I encountered the notion that maybe matters of the heart and matters of the mind bring us to a common place.

People try to draw a hard line and the line's not real.

This has been amazing, as I knew it would be, Ellen. I'm so grateful for your time. It's been so much fun to talk with you. I loved every minute.

Thank you for having me. This has been crazy fun and very helpful and extremely thoughtful on your end with all the questions. I'm beyond honored.

This article contains Amazon Affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.