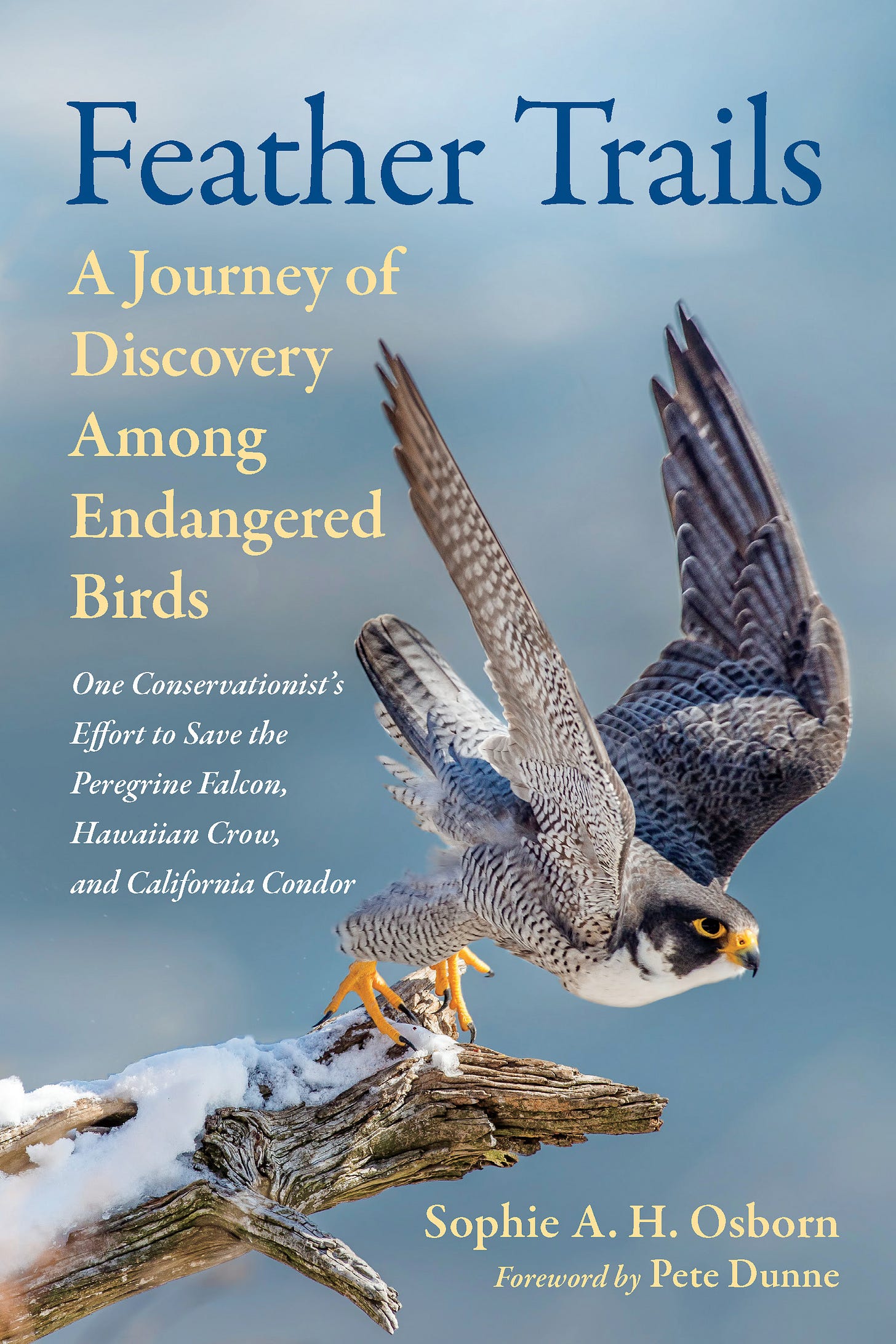

Last spring, my friend Bryan McGrath mentioned a new book he felt eager to read – Feather Trails: A Journey of Discovery Among Endangered Birds, by Sophie Osborn. Earlier, Bryan wrote about the Merlin Bird ID app from Cornell University, which had transformed my walks in nature. Suddenly, rather than merely hearing a bird singing nearby, I could quickly and easily identify it – and usually numerous other birds picked up by the app that I, too, could enjoy if I listened with a touch more attention.

So when Bryan mentioned Sophie’s book, and her companion Substack, Words for Birds, I felt drawn to check them out. I subscribed to her Substack and ordered the book. They were two of the best decisions I made in 2024.

Sophie beautifully weaves together her story with lovely nature writing with the science of bird decline and the potential, along with the immense work required, for population renewal. To say I loved Feather Trails massively undersells it. Of the 50 books I read last year, it was one of my top 3 reads. I’m not alone: the Birding Book Club of the American Birding Association named it one of the Best Books of 2024.

At my request, Bryan kindly introduced Sophie and me late last year. We enjoyed a couple expansive and splendid conversations. Finally, I asked Sophie if I could interview her for “Walks of Life,” and she generously agreed.

A few points stood out during our talk, and my subsequent reflections.

We think of human individuals, but less so about animals. Rather, we have a concept of “tigers” or “sharks” or even larger groups like “birds. Sophie’s book and our talk brought home how different and distinct individual animals are. The individual California Condors she worked with exhibited very distinct and unique personalities. On my walks now, I find myself wondering about the singular characteristics of a squirrel I see, for example. I likely will never know, but because of Sophie, I know that squirrel is, in some ways, a true original.

Sophie also noted the profound instinct to play among the birds she worked with. For some reason, I see that instinct in my dogs, Olivia and Otis, every day. But I had never considered that other, less domesticated, animals might possess a similar yearning for playfulness. The world seemed a brighter place for Sophie highlighting that revelation in her work.

At one point in our talk, Sophie indicated that occasionally she mis-identifies birds she hears or sees. Not often, but it does happen. It reminded me that we make mistakes even in our areas of profound expertise. It was a refreshing, and human, admission – and a useful reminder for me to have patience with myself when, I, too, make mistakes in my (supposed) areas of “mastery.”

Enjoy! And, again, thank you, Sophie!

Sophie, thank you so much for joining me. This is awesome.

It's a thrill to be here. Thanks, Russell.

I loved your book, Feather Trails. It was one of my top books of the year. Top two or three books of the entire year. I loved it, and I just can't wait to talk about it.

I'm thrilled that you liked it. I think that's amazing. I really am excited about that.

The book and your newsletter have inspired me to care more about birds and bird watch a little bit and certainly as I go for my walks in nature, pay more attention to birds and the sounds and the sights I see as I go about those walks.

That's fantastic. That was one of my major hopes in writing this book – to see if I could interest more people in the world of birds by writing about my adventures with birds and my dealings with them. So that's exactly what I had hoped would happen.

Let's kick off my questions. I'd love to just hear you talk about your career with birds and what your favorite role with birds has been.

I've been lucky to have a lot of years in the field with birds, researching them, conserving them and reintroducing endangered birds to the wild. Reintroducing birds to the wild has been the real highlight. Whenever I was out there helping these really rare endangered birds get back out in the wild and make it, I always felt like I was doing something of value and something important.

Every day I was out there, it felt meaningful and important. And I really loved that. It felt like I was doing a critical thing to help the planet to help our bird life. And to help all those who care about birds by getting these birds back there in the wild. And I also loved it because when you are working with endangered species, there's often very few individuals left, so I came to know the individuals that I was working with really well. When you get to know individual birds, a lot of them have really unique and different personalities. It was so much fun to get to know them. I, of course, became very attached to them. I try to convey some of the stories of my experiences with these different individuals in Feather Trails.

So why do you think we humans are attracted to birds? Why do we feel this connection to birds that we don't feel for any other animal except maybe our dogs and our cats?

Exactly. A lot of people say that it's because we're drawn to their ability to fly. But for me, it's their color and their sound.

Birds are beautiful. They fill our world with music. They're these fragile, delicate creatures, and yet they do these amazing feats – like migrate over hundreds of miles of water. They connect us to different parts of the world through the magic of their migration. One of the things that really attracted me to the bird world was that their whole lives are often on display for us.

I first was interested in mammals, and I wasn't a big bird person initially. I especially like small cats. But I realized that if I ever wanted to work with small cats they're usually nocturnal or they're hidden. They're cryptic. A lot of mammals, their lives are hidden from us. They're in the dark or we just don't see them. But with birds, you get to see them feeding their young and fighting over territories and singing to proclaim their territories. They're so visible and they live all around us. It's much easier for us to see them and appreciate them and experience their lives alongside ours. So for me that's a big one.

What do most people get wrong about birds? What do they not understand about birds? What do they miss about birds?

A lot of people aren't aware of how many birds are around us. And the variety and the diversity. Until I really started getting into birds and studying them, I had no idea how many different birds there were around living their lives around us.

We also take for granted that they'll always be there, no matter what we do, because they're pretty resilient, but we could push them to a certain point where a lot of their populations are declining. A lot of them are not doing well. It behooves us to take notice of them and help them out when we can.

You mentioned some of the bird personalities, Sophie, and there were some moments in your book that I laughed out loud, cracking up when you saw a bird do this or that or you had an interaction. Tell us about the funniest thing that's happened to you as an ornithologist.

Some of these birds are very charismatic. I used to laugh working with California condors so often. You wouldn't think that a big ugly vulture would be that appealing. But when you work with them, you discover that they're really playful. They were often playing tug of war with things. Anytime they saw an empty water bottle on the beach, they would have to punt it like a soccer ball, and they would just chase after it. They'd fight over these fun toys, and I always knew that if there was a collection of condors in an area, they'd either found some food — a carcass — or else they'd found a bunch of really fun toys.

Once at the Grand Canyon, this garbage can had blown over and the contents had blown over the canyon. I went to the edge of the cliff rim and looked down. It was just a play fest of condors. One of them was standing on the lid, and the other was trying to drag the lid, another was punting a water bottle down the slope and leaping over bushes to get to it. It was crazy, it was a total play fest. The times I've laughed the most is when they're doing these incredible weird interactions and just playing, which is amazing.

It sounds like we should have them over and like open presents under the Christmas tree. It'd be like, it'd be like having more kids.

They would love it. They are so into playing with anything that they can get their beaks on. That's just a fascinating aspect of birds. Also, birds allow you to laugh at yourself and not be too overconfident – I remember having some funny moments in my life with just incredibly bad calls that I've made. I remember once being all excited going to a wildlife refuge. I was with a friend and I said, “Oh, an incoming flock of ducks.” And he looked at me and said, “Sophie, those are blue Jays.” In my enthusiasm at the moment, I just completely blew it. But we all often do when we're watching birds, there's challenges out there. We get overenthusiastic or we don't see something the right way. We can all make mistakes and remain humble while doing it. So I've laughed at myself at times.

I have to ask a kind of snarky question. You love birds so much. That is evident in our conversation already. It was very evident in your book. I'm just curious. Are there any birds you can't stand? Any birds you hate?

I guess hate might be a slightly strong word, but I do have to confess that there are some birds that I don't love very much at all. It's not even their fault, but I have to say that one of my least favorite birds is the House Sparrow, which is one of our most common birds in cities and towns.

I'm not a fan because it was introduced from Europe, and it's really aggressive about getting nest cavities from our birds. Nest cavities are very limited, and Swallows and Bluebirds nest in them. House Sparrows will go into those cavities, and if there's already Swallows or Bluebirds nesting in there, they'll sometimes kill the young nestlings and build their nest right on top, and take over the nest.

So I don't like them. They are making it much harder for our native birds. Same with European Starlings. That's another introduced bird.

As far as the native birds go, I love them all. Some of the introduced birds, I don't love them because they put so much pressure on our native birds. It's not their fault. European Starlings do the same thing as House Sparrows. They compete for these cavities that are limited. Starlings are at least very smart and they're amazing mimics. So they have those sort of things going for them. Whereas House Sparrows just make me cranky when they come around and try to take over my Bluebird nest boxes. I chase them off and scream at them.

Wow. Sparrows, starlings – you have earned Sophie's ire.

I'm afraid they have. It's not their fault. It's us messing with the world a little bit.

Let's turn to the book for a few questions, Sophie. Can you update us since the events of the book? Tell us what's going on with the preservation efforts for the Peregrine Falcon, the Hawaiian Crow, and the California Condor. How are they doing today?

The Peregrines are doing really well, by and large. They were taken off the endangered species list in 1999, and they're one of our biggest conservation success stories. Unfortunately, biologists right now are really concerned because we're starting to get a lot of reports of Peregrines dying because of avian flu.

The avian flu is really wreaking havoc on our bird life right now and apparently Peregrines are getting hard hit by that. So I'm a little worried about them from that perspective. I'm also a bit worried because we're having a catastrophic disappearance of our insects and Peregrines rely on birds to raise their young. Many birds feed on insects. And so if there are fewer insects, the birds that feed on them are going to be struggling and there'll be fewer of them. So I'm a little worried about the long term, but so far the Peregrine has really been a remarkable success story, where people got behind it and helped return it to the wild.

California Condors are doing really well. They went down to 22 at one point, and now there are over 500 of them. There are over 300 in the wild, so that's also a very good success story, but they still require intensive management. Without our help to save them from lead poisoning, they would go back toward extinction. So they're doing really well, but they're very dependent on our management. And the Hawaiian Crow – their situation has turned around recently, and it's very hopeful. In my book they were one of the sort of saddest stories. They've really struggled and had a lot of pressures that they've been up against.

Five of them were just released onto the island of Maui. So it's the first reintroductions that have taken place in a couple of years. And they put them on Maui, which is not their native island. They are native to Hawaii, the Big Island. But the Hawaiian Hawk, which has exacted a lot of pressure on reintroduced birds, doesn't occur on Maui.

They want to give these birds the best shot they can in the wild. They've just reintroduced some birds and so that's really exciting to finally have Crows back out in the wild. That's exciting. They're also trying a biocontrol to reduce numbers of mosquitoes in Hawaii. Mosquitoes have been a big problem transmitting diseases to the native birds.

So there's some good news on all fronts, which is exciting. It just goes to show when we have targeted conservation efforts and really try to help these animals, we are often very successful.

That leads to my next question. Something that came out of your book and especially with the story of the Peregrine Falcon – when a bird becomes endangered, it sure seems like the 80-20 rule is in effect. Eighty percent of the problem is caused by 20 percent of factors. With the Peregrine Falcon, it seemed even more dramatic. 90-10 or 95-5 The overwhelming problem with Peregrine Falcons was the introduction of DDT and related chemicals into the environment.

The solutions also seem to follow a similar distribution. Twenty percent of the solutions get at 80 percent of the conservation effort. Again, with the Peregrine, getting DDT nixed from the market significantly improved population health. And yet, something that came out of your book is that ornithologists kept pushing on all fronts. You kept hammering on the 80 percent of the solutions that contributed only 20 percent of the solution. I found that fascinating and I'd love to hear from you: Why keep pushing on all fronts, even ones that won't seem to contribute that much to the general result?

You're absolutely right. One thing I did try to convey in my book is when there's a bird like the Peregrine that is basically declining for one reason, if we don't deal with that primary problem, we're not going to be successful in recovering this species. So we were able to get rid of DDT and that helped the Peregrine.

If we could get rid of lead ammunition and replace it with non-lead ammunition, we would take care of the Condor. But a lot of the time, those big threats are so difficult for the general public to deal with. It takes agencies, it takes biologists, it takes non-profit organizations, it takes a lot of entities to work on some of these larger problems like pesticides, like climate change. Right now we're in an all hands on deck moment with bird declines. We've lost about three billion birds in the last 50 years. A lot of us in the general public feel overwhelmed trying to think, how can we help?

I can't stop agriculture from using too many pesticides, but I can keep my cat indoors and put decals on my windows to try to protect birds. A lot of what I was trying to do was inspire people to take care of those other factors that we can deal with.

A lot of birds are disappearing and dying – a death by a thousand cuts. There's a lot of different pressures on them. The more of us that can help with some of those pressures, then hopefully the agencies and the bigger conservation groups can deal with the bigger problems. If the rest of us chip in and help with the smaller problems, then we have a better chance of helping out more birds.

That's an enormous number. You just said 3,000,000,000 lost in 50 years. Basically, my lifetime.

It's really staggering. Something else I tried to convey in my book – we often look back to our childhoods as this time when there was more wildlife, less development, and it was a wilder time. But children today are growing up in an environment with far fewer birds and much less wildlife than we grew up with. And we had less than the generation before us.

There's this disappearing wildlife that we adjust to. In this book I wanted to show, especially in Hawaii, what it was like so that children today know what we should try to work to save, what we should work to try to get back to, to recover some of these lost birds and lost species, lost habitats.

That leads to a tough question. Can we have our proverbial cake and eat it too? Can we have the benefits of a modern industrialized society and can we also have a thriving natural earth ecosystem, where wild animals can live in some reasonable equilibrium with the human-created industrial society?

I think we can. It's important that we're clear-eyed about our impacts, that we learn about them, and we recognize and we make changes that help minimize our pressures on other organisms. But I learned with endangered species – by helping birds, we often tackle problems that harm us too.

Getting rid of DDT doesn’t just help peregrines. It was very beneficial to the environment and to us too. So we definitely benefit by reducing threats to birds. An amazing conservationist said that when we take care of birds, we take care of most of the environmental problems in the world.

A lot of those things are threatening us too. We can have development. We can have our modern industrial society. But it's valuable to recognize that we are sharing the planet with other organisms. By sustaining them, we sustain ourselves too.

Some of that is more nebulous – in addition to birds pollinating our crops or keeping our insects to a safe number, birds do all kinds of things to contribute to ecosystems.

Also – being in nature is restorative for us. It's healthy for us. There have been a lot of studies that show that getting out and walking in nature makes us happier, makes us less stressed out, and makes us less anxious. I think we can find a balance there where we can continue to live the lives that we want, but also nurture and sustain the wildlife that enriches our own lives and that shares some of the problems that we face, too.

In the world of bird protection, what's the frontier? It undoubtedly involves technology in some way, shape or form. What's that look like? Tell us about the frontiers, the leading edge of your world.

There's so many of them. There's so much research on birds because they are so visible and vocal. There's always a lot of research on them because they're easier to study. But people are focusing more on their entire life cycle, not just the summer or spring. Many of them migrate huge distances and winter in the tropics.

People are starting to look more and more into their wintering habitat. And also what's happening to the habitats where they stop over and refuel when they migrate. There's been some amazing new research, and technology is key. For example, there's a new thing called the Motus Tracking System. They put tiny little radio tags on birds and insects, and towers track the animals as they pass by. They're able to find out a lot more about tiny organisms like birds and insects as they're migrating. That's one of the really amazing new kinds of frontiers of wildlife tracking.

Then there's a lot of technological advances that are more subtle, but are really important. They're constantly trying to study how to make glass safer for birds. A lot of birds crash into buildings during migration. Now there are different studies to try to make glass more visible to birds to help protect them.

There's some things that are less technological, but have made a huge difference over the years. For instance, when you see radio and communication towers that have red lights on them to warn planes. They discovered years ago that birds were getting drawn to these red lights and circling the towers until they were exhausted or hitting the guy wires and dying. They made a simple switch – from the steady red light to a blinking light. That really improved the problem.

There's a lot of research going on in how birds are impacted by all sorts of things. There are a lot of people chipping away at these different pressures on birds.

You were talking about the Motus Tracking System. It sounds like every bird is going to get its own Apple Air Tag.

I know! Exactly! It is a lot like that. It is amazing what these technologies reveal about these migratory journeys, and where these birds are traveling. It's just incredible.

Let's look at the flip side of this coin. What're going to be the hardest challenges in protecting birds over the next 50 years?

I think it's our ever-growing population and the pressures that we exact on wildlife in its habitat. We need so many resources to feed and house and clothe ourselves. There's often either an unwillingness or an obliviousness about the wildlife and the habitats around us. Becoming more aware that there is wildlife around us, that they are trying to make a living is really valuable. But I think it is our ever growing population and trying to come up with creative ways to sustain wildlife and wildlife habitats as our numbers increase.

In your book, you mentioned so many people, researchers, scientists, ornithologists, and organizations. Tell us about one unsung hero in bird preservation – a person, an organization, anybody unsung who's doing heroic efforts to contribute to the effort to save birds now.

I couldn't really think of one person or one organization necessarily because it does take a village. There're so many people involved, as you suggest and I tried to convey in my book. But for me as a group, one group of unsung heroes are often the field biologists – the people who are out there in the field day to day, working to research these birds, conserve these birds, reintroduce the endangered birds to the wild. It's often the higher ups that are doing the administrative stuff and the policy work that get a lot of the attention. But people on the ground are often dealing with terrible weather and unbelievably long days; birds don't take off Christmas and New Year, so the field people work through weekends and holidays and everything else.

And I tried to give a thank you in my dedication to the field people because I think they're often our unsung heroes in keeping our bird life healthy and happy.

That also very clearly came out in your book. You talk about some of the walks you took – enormous distances to try to find a bird's nesting place or, unfortunately, to try to find the carcass of a bird. Tell us a little bit about those walks. My newsletter is about walking and I'm fascinated with those walks that you took as a field biologist. What were you thinking about? what were you feeling? What were those walks like?

Sometimes the walks had a purpose. If I was looking for a bird that I suspected had died, I was of course anxious – I was hoping I wouldn't find a dead bird. When I was looking to try to find if the birds were nesting, that was very hopeful. So I was often thinking about what I might find at the end of my destination. But I never lost sight of how much I loved the moment and being in nature and experiencing the natural world around me, because it is really just amazing to be out there in the wild.

It's often quiet. I did take some very long journeys. One thing I really ended up doing a lot at the Grand Canyon, which I had never expected, was hiking at night. It was so hot down in the canyon during the day so we had to do our hikes in at night.

I had never hiked alone, at night, for 12 miles. I would hear the echolocating noise the bats were making. It was peaceful and beautiful. It was just a magical time to be hiking with very few people around – whereas in the Grand Canyon, the daytime was crowded with tourists.

Mostly it was just being out there with nature and really enjoying the moment, while also sometimes worrying about what I was going to find when I completed my journey.

I love that. Tell me about your favorite place to take a walk, period.

My favorite place really is mountain country. I spent my early years in Switzerland and then moved to Vermont. I just love mountains. My favorite walks are always along mountain streams or through woods that get me up to a mountain lake. I love those. I love the rushing, tumbling mountain streams. I love having jagged peaks around me. I love mountain country. That's probably my favorite.

That's amazing. This may be a similar answer, but I'm curious – I've started to ask a few people in life this question, and I'm always fascinated by their answers. Where do you encounter beauty in life?

A lot of it is mountain country. I ended up working with condors in Arizona and canyon country is beautiful, but it wasn't the same for me. So I spent years trying to get back to the mountains. Looking out at a mountain range and the alpenglow, the different light on it at night, is something that I love.

I love so much seeing the ever-changing light in the sky around mountains. But almost wherever I am in wild places, I end up seeing beauty – big and small – small flowers in the forest floor or a Tanager perched up in a tree. There's so much beauty around and I really enjoy that.

There's also beauty in our relationships with other people and our pets. It's not a visible beauty, but our important relationships with animals and people are a beautiful thing too.

That's wonderful. I love it. Let me ask you a few last questions here, Sophie. For beginners, and I'm definitely a beginner, what's a good resource to learn more about birds, birdwatching, identifying birds, or the state of birds period? What are good resources for people to turn to?

There's more and more online. Maybe it's because I started out years ago, I'm more old fashioned: I think it's really nice to have a field guide to be able to look at just how the birds are laid out, and compare birds in an easier format. There are some really wonderful field guides. The Sibley Guide to Birds is a great one. He has beautiful pictures of birds that are really helpful for identification. I grew up using the Peterson guides, so there are Peterson's Eastern and Western guides. Those are amazing. And Kenn Kaufman has a book of bird photographs if people prefer to identify birds with photographs instead of drawn pictures. His Birds of North America is great.

As far as apps go, Cornell University has just done a brilliant job with its Merlin app. They've transformed the bird world and made it so much more accessible for beginners through that app. I haven't used the identification portion of it because I usually know what I'm seeing, but I do use their bird songs and calls part of it.

You can hear a bird song that you're unfamiliar with and hold up your phone, record it, and the app will tell you what you're hearing. That's amazing! Even for somebody like me, there's a lot of places where I'm not familiar with the birds or I'm rusty or I'm confused.

It really is an amazing app as far as telling us what's around us all the time. For new people, sometimes you think, “Oh, there's probably three or four birds around.” And you hold up your phone and suddenly, you're hearing birds singing that you didn't even know existed. It can be a lot of fun.

Those are my favorites.

That app is incredible. Our mutual friend, Bryan, mentioned it in one of his newsletters and I got it. It has transformed my walks in nature. It is the coolest app. It's awesome.

Yeah, it's a free app and it's phenomenal. Very occasionally it will have a mistake, but for the most part, it is wildly accurate and it's tremendous. It really does open up the world. One of the things as an ornithologist that I loved was learning bird songs because suddenly, you realized how much is around you that you didn't even know was there. And Merlin does that for you.

You mentioned a few books. Besides, of course, your book, what are your favorite books about birds?

It's funny. I don't have that many favorite books about birds. It's just crazy. Some of them are quite a lot older – my favorites are the ones that sort of started getting me into birds. But one of my favorites is Wings for My Flight: The Peregrine Falcons of Chimney Rock by Marcy Houle. It was about her work with wild Peregrines. It came out a couple of years before I did my Peregrine work. That really resonated with me. I love the stories of biologists being out there, doing the work. Not surprisingly that resonated with me.

There was another book – this wasn't about birds – called Cry of the Kalahari about biologists working in Africa. It had a similar kind of impact on me. I must've been drawn to these stories about biologists working with birds.

An amazing bird person named Pete Dunne, who actually wrote the introduction to my book, which was a huge honor, has a bunch of wonderful bird books. He has a new one out that I haven't read yet, but one of his older ones was called The Feather Quest. He and his wife went all over the country looking for birds. It was the first time I realized you could travel and see new birds in new places, and that was a revelation at the time. You could get to know the birds in your neighborhood, but then you travel and there's a whole other contingent of birds to experience and learn about and discover. He really made that clear for me. So I love The Feather Quest.

I love it. You mentioned a couple of ideas about how we private citizens can help birds. My daughters, who are 10 and 12, saw me reading your book and they asked me about it. Then I mentioned that I was going to interview you and they were all excited. Maybe they'll listen to this or read this. They had a question, which is: how can they – again, they're not experts and I'm not an expert – but what can they do to help protect and save birds?

It's hard to think of just one thing that people can do, because a lot of my philosophy is that there are many small things that we can do. But the number one thing is to open our eyes and be aware of birds – to notice birds and to learn about them.

A lot of us don't realize how much diversity there is around us– how different these birds are. They all make a living in a different way. If you see birds in your yard, look them up, try to figure out what they are, learn a little bit about them. As we learn about birds and we observe them, we often come to care more about them, especially when we see them and they're familiar in our backyards. When they become familiar and we know about them, we can share our stories about them. I think that makes us want to help them. That's a critical first step.

There are a lot of things that we as individuals could do. Wildlife likes dark places. We can keep our lighting outside darker. You could tell your daughters to turn their lights out when they leave a room. It keeps the house darker for the birds. Or they can put decals on the windows, because birds often strike windows. Keeping our cats inside is a really big one. The biggest pressure on birds is cats – keep your cats indoors. Other things are plastic beverage containers. There's a circle there that birds could get trapped and tangled in – cut them so animals don’t get caught. And cut the rubber bands that you take off of fruit or broccoli.

Just be aware that there's a wild world around us that could be impacted by our lights, by our cats, by our trash. Try to take care of some of those things. It's small stuff, but if there are 96 million birdwatchers in the U.S., even if 20 million do some small thing, that’s a lot.

Huge difference, yes. This has been awesome, Sophie. Let me get you out of here on this last question. After your book, what's next for you? What's your next project?

Right now, I'm working right now with a fellow biologist to create an anthology of stories by and about women biologists who are doing work all over the country – amazing work with wolves or crayfish or other animals. It's all their various adventures in the wild – crashing in helicopters, getting bitten by a bear in Yellowstone, dealing with poachers in Panama, dealing with a flood in Alaska. We finalized that book, so I'm working on getting that published.

It will hopefully show young girls and women that working with nature and wild animals can be an amazing experience and amazing career, and people really thrive at it.

I love it. I can't wait to read it. This has been an amazing conversation, Sophie. I loved your book and talking with you. They really have been highlights of my year. I've loved every minute of it and I can't thank you enough for your willingness to come and chat with me.

It's such a great pleasure. I love sharing birds with people and it's just so exciting when people are starting to get captivated by that world. There's nothing better for me.

Absolutely. Thank you so much, Sophie. I really appreciate it.

Thank you, Russell. Great to talk to you.

(This article contains Amazon Affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.)