Silver Medalist: June Carter Cash

Press on. And forgive.

The entire universe is vibration. The entire universe is motion.

Can you feel the vibration? Inside you, outside you, every moment, every day, every where.

The entire universe is laughter.

Humming. Rhyme. Story. Music.

Song.

Listening to June Carter Cash sing, you will note her singular voice, distinct from the likes of Dolly or Linda or Wynona or Tammy or Patsy. Contrary to her self-appraisal, she was an excellent singer. But she was rarely the best singer on stage. That honor usually went to her legendary husband, Johnny Cash. But June wasn’t even the best singer in her family band, Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters. That title probably went to her younger sister Anita. And, well, her older sister Helen may have sung with greater skill too.

June did not let her relatively limited singing ability — when compared to the superlative greats — forestall her career. She found ways to contribute to a show’s success. She was a gifted comedienne. She worked hard to learn acting, which paid off on the screen and stage. Interestingly, while June's husband, Johnny Cash, would gather acting roles because of his fame, his performances came across as forced, stilted, and unnatural. Her acting, on the other hand, while not Academy Award-worthy, was accomplished and purposeful.

June Carter Cash cultivated herself into a wonderful entertainer.

She felt happy and content contributing to the greater good. She needed the spotlight, but she honored the need for others to have the spotlight even more. And she didn’t feel threatened by that need.

“Sadly, I think her contribution to country music will probably go unrecognized simply because she’s my wife; it certainly has been up to now. That’s regrettable — my only regret, in fact, about marrying her,” Johnny Cash wrote.1

So what makes June Carter Cash a Silver Medalist? Longevity, for one. Her career began in 1939, at age 10, and ended only a few weeks before her death at 73 – more than six decades of performing and recording.

The first time Johnny ever saw June, she was performing on the stage of the famous Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tennessee — which he was visiting on a high school field trip. Across that long span, she played with nearly every country music star of the 20th century — and many rock & roll icons too. They included Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, Waylon Jennings, Bono and U2, Willie Nelson, Patsy Cline, Hank Williams, Hank Williams Jr., Kris Kristofferson, Roy Orbison, and many others — including her own Mother Maybelle, who had been a member of “The First Family of Country Music,“ The Original Carter Family.

Amidst the celebrity, money, properties and travel, June has lessons to teach about ambition, place, faith, success and family. Not all of them are lessons to be admired or imitated.

For decades she courageously confronted her husband’s drug addiction. Then her son’s. Then her daughter’s. Other family members struggled with addiction. So did she.

Through it all, she kept going. She enjoyed her greatest personal success in music in her final years. Her marriage to the man she called John was firmest in those final years, like a meteor flaming brightest before disappearing in the atmosphere.

Today, twenty years after her death, she is largely forgotten. In some ways, Johnny has never been bigger — his legend grew in the decades since his passing. Johnny was a musical genius — a true legend.

June was not.

Part 1: The Entertainer from Poor Valley

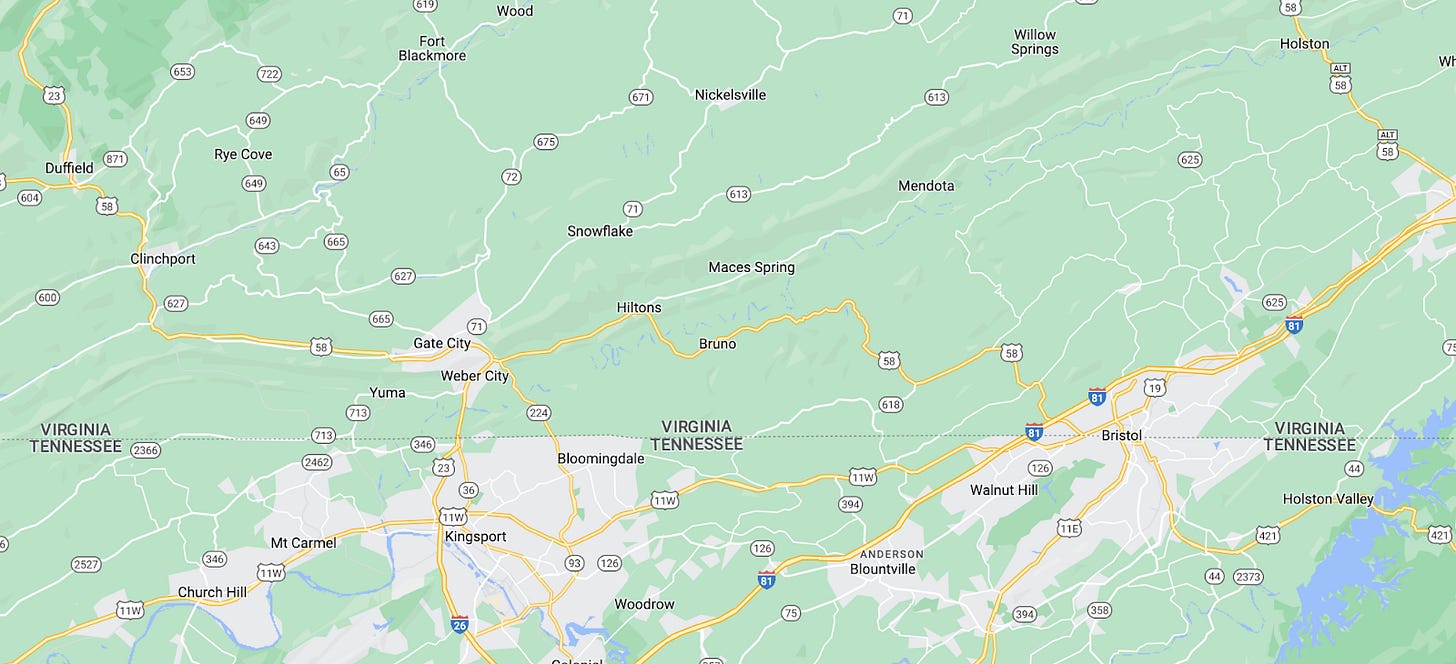

To know June Carter, we must know her family and her birthplace. June was born into a musical and innovative family. Her mother Maybelle, cousin Sara and Sara’s husband, A.P. Carter formed the Carter Family, one of the earliest country music radio and recording acts. Sara would earn money singing at nearby events; sometimes Maybelle would join her, playing the guitar in a way called the “Carter Scratch.” The Carter Family became a more formal act during the summer of 1927, when A.P. saw an ad in the newspaper. The Victor Company was bringing a recording device to Bristol, Tennessee, and would pay $50 — a huge sum at that time — for every song it “deemed worthy of recording.”2 Sara, A.P. And Maybelle drove to Bristol for the audition; they headed home $300 richer. “The First Family of Country Music” had its start.

A year earlier, Maybelle had married A.P.’s brother, Ezra “Eck” or “Pop” Carter. Eck was a curious and energetic man. He became an important man — as a railroad postal agent and later the builder of the first dam in the area, bringing electricity into his home and then to the surrounding area. He was a “resourceful, deep-thinking man who loved tinkering and working with his hands. He always saw intriguing possibilities where others saw difficulties. He supported and believed in Maybelle’s music and her amazing ability to play her guitar.”3

In September 1927, only a few months after the first recording of the Carter Family, Maybelle gave birth to their first child, Helen, in Maces Spring, Virginia. June Carter – full name Valerie June Carter was born in June 1929. The youngest Carter sister, Anita, followed in March 1933.

The area where June and her sisters grew up, at the base of Clinch Mountain, was known as Poor Valley, and we don’t need a strong imagination to know why. The Holston River flowed barely a mile away from the Carter home. Rolling hills and taller mountains framed a rugged, picturesque setting for June’s first home. She fell in love with this area. Even when she would leave this place to play and record with her family, even as she became a mainstay of country music, even after she married Johnny and enjoyed lavish homes in Nashville, New York, Florida, Jamaica and other places, this place would remain her center. She would always call it home, think of it as home, and feel it as home in her heart. She would return to it for emotional and spiritual renewal to the end of her days. All her life, the music, laughter, religion and folklore of this place would echo in her soul.

While her mother traveled around with the Carter Family, June spent much of her early years following her father Eck around. “I wanted to be a Daddy’s boy,” she wrote in her first memoir.4 She would ride on Eck’s motorcycle, swim the Holston, worm tobacco, play basketball and milk cows. She was “happiest when she was in mud up to her waist.”5 For the first 9 or 10 years of life, she rarely went beyond the four square miles around her house.

A.P. and Sara Carter divorced in 1936, but the Carter Family kept singing together. They went all around the area, singing at events and performing on radio shows. In the winter of 1938-1939, Maybelle, A.P. And Sara went to Del Rio, Texas to sing on station XERA two times per day for six months. Later in 1939, XERA signed the Carters to a new singing contract — and it included the three Original Carter Family members, and their families, including the kids. Helen, June and Anita moved to San Antonio to sing with their family.

From a young age, Helen and Anita sang beautifully. June sang well, but not with the ease as her sisters. In June’s words, “My two sisters, Helen and Anita, had perfect pitch, but no matter how hard my mother tried or Anita pinched or Helen glared, I’d sing anywhere on the scale that my voice decided to go at that particular time. And it was never where they were.”6

In those days in Texas, the first hints of June’s greatness emerge. She worked hard to improve her singing. She wanted to sing as beautifully as Anita and Helen — and her mother. “When you don’t have much of a voice and harmony is all around you, you reach out and pick something you can use. In my case, it was just plain guts.”7

June also found other ways to entertain an audience. She wrote, “I talked a lot and tried to cover up all the bad notes with laughter.”8 Her son, John Carter Cash, later wrote, “a little light went on in her head as the audience chuckled at her antics. Maybe she wasn’t the family’s most talented musician, but she could be funny, and an audience’s hearty laughter was as welcome to Mom’s ears as applause. She had learned a valuable lesson.”9 In fact, she had learned two lessons.

Lesson: Fit In

June realized from an early age that music ran in her family’s blood, like the Halston so near her family’s home. Despite not being the greatest singer, she embraced her family’s work. She joined her family’s band and became an integral part of their music and identity.

Lesson: Stand Out

That said, June felt an ambition — different from her sisters — to distinguish herself within the Carter Family. She wanted to stand out and sought ways to do so. Her monologues and comedy bits helped her stand out and made a unique contribution within her family. This drive to stand out would show itself again and again. It would push her to improve her singing, her playing the autoharp (her main instrument), her comedy repertoire and later drive her into acting. In her later career, she would have many tools to call upon to captivate an audience, whereas her sisters, her mother and even Johnny would rely on only their singing to engage an audience.

In her first autobiography, Among My Klediments, June related a story that illustrated this point well:

“Oh, I had such great ambition to be a funny girl. When I was ten years old, I met Cousin Minnie Pearl, famous for years as a comedienne at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, and she encouraged me. She said, “Always be yourself. Never try to copy or mimic anyone else. Be an individual.” So I went home to the valley and started to live with my dreams of being a funny girl. The week after I talked with her, Cousin Minnie sent me a letter and a lot of routines she had used on the Grand Ole Opry. That was the most wonderful thing that could happen to a girl who had dreams of being a great entertainer. In the years that followed, I learned Minnie’s routines, and I felt very special because she had taken the time to write me when she was such a big Opry star. But I followed her advice, and I never once used one of those routines. I developed my own.”10

After a couple years in Texas, the Carters returned to Poor Valley. Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters kept playing music throughout the Valley and surrounding area. They became famous enough that they were photographed to grace the cover of the then-renowned Life magazine — scheduled for the first week of December 1941. Of course, the attack on Pearl Harbor dropped their cover moment. But it was a testament to their musical reach and impact that they had been scheduled for the cover in the first place.

In late 1942, the Carters, including A.P. and Sara, moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, to play on radio station WBT. Like before, they played live on the radio every day, and in the evenings played live shows around the area, arranged by Eck. These months in Charlotte proved to be the last hurrah for The Original Carter Family. After the contract expired in the spring of 1943, Sara, Maybelle and A.P. would never play together again.

Maybelle, Helen, June and Anita moved on to Richmond, Virginia, with a new radio contract. In Richmond, June graduated from high school. She wanted to attend college, but the family needed her as a part of the band. “So we had our homemade college — the guitar, the songs, the road work, putting up public address systems….In the traveling we did I learned to sing all the parts, take up tickets at the door, drive all over the USA, and do what was necessary to make a good show….The old circuits sometimes called for five shows a day. I learned to sleep in the car, get ready in five minutes, and tune a guitar in two….My body ached. Then I stopped a show with a routine, and I finally had to face it — I was hooked. There would be no turning back now. I would be an entertainer.”11

In 1950, the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville came calling for Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters. There was no greater stage for a country music musician than the Grand Ole Opry. It’s like being named a don in the mafia, an unmistakable signal that the artist has ascended to country music royalty. Almost every single country music star in the past 75 years has at least played at the Opry. John Carter reflected, “Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters had reached the top of the ladder. They were regulars at the Grand Ole Opry. What a rush that must have been for these plainspoken people from the mountains, what a sense of accomplishment they must have felt.”12

In the whirlwind of stardom, June married another emerging country music star, Carl Smith, in 1952. They had separated even before their daughter, Carlene, was born in 1955. They divorced shortly thereafter. In 1957, she married Rip Nix, a race car driver and former football player. June gave birth to her second daughter, Posey, the following year. June and Rip divorced in 1966.

Following her divorce from Smith, and then many times later in life, she went to New York City to retreat and recover. Her son wrote, “I can’t help but think that first trip to New York forever influenced her life. She saw the fashion, the style, the opportunities, the money, and the education the city offered. When her marriage to Carl Smith ended, she felt New York beckoning her. Come here and recover, the city seemed to say to her. Come here and change. Make a clean break. Begin again.”13

Lesson: Know Your Home

June would always view Maces Spring and New York as her havens, the places she could gather her strength. She returned to one or the other again and again. She viewed them as her true homes, regardless of the amount of time she could spend in them. The author Wendell Berry writes about the necessity of place, of living in a place and knowing it. He writes beautifully about home. The reality of today’s world, with digital nomads, children living far from parents, and diverse family arrangements, makes living in one single place a challenge or impossibility for many people. June offers a useful, practical bridge between Berry’s vision and that reality. Even amidst a nomadic life, she points toward the beauty and usefulness of grounding oneself in a place or two, and gaining emotional sustenance from them. The amount of time spent matters less than the emotional connection.

In New York, June dove into her acting career, taking lessons, seeking out roles and continuing to expand her entertaining talents. She returned to Nashville on the weekends to play at the Opry, then headed back to New York during the week.

By 1961, June had a thriving singing career. She was a country music star and a regular at the Grand Ole Opry. She was growing her skills as an actress. She could enthrall an audience with her comedy. She was one of the great American entertainers of the day.

She was also a mother of two daughters and a wife. While she wasn’t looking to slow down, she wanted a streamlined schedule to have more time in Nashville with her family.

Johnny Cash hired a new manager around then, Saul Holiff. And Saul thought June would make an excellent addition to Johnny’s traveling tour, the Johnny Cash Show. That tour traveled 10 days each month, leaving 20 or 21 days for June to return home to her girls. That appealed to her.

On December 5, 1961, June joined Johnny’s show at the Big D Jamboree in Dallas, Texas, “a date I knew was going to be the start of something big,” Johnny wrote.14

Part 2: June and John

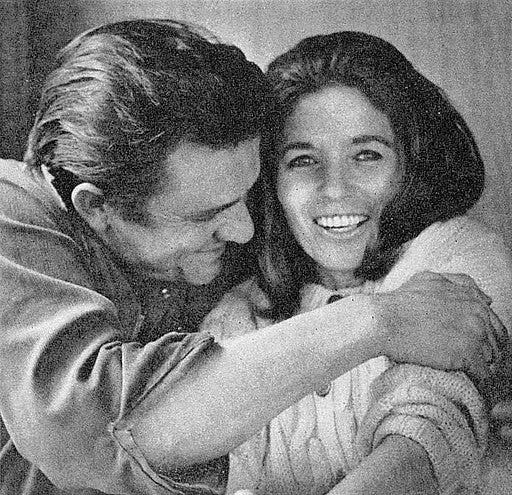

In the video for “Hurt,” Johnny Cash’s cover of the Nine Inch Nails song, the camera flashes a couple times to June looking down at Johnny. The video director, Mark Romanek, added her after “June walked from her bedroom to the stairs and looked down at her husband….When Romanek noticed her, he was struck by the anxious, loving look on her face.”15

Johnny and June looked like they were in their mid-80s, but were in fact only in their early 70s. The pain, joy and complexity of the decades together shone out of June’s face in deep and sincere concern. Not regret; not that emotion. But recognition of what had been and what would soon be gone.

They filmed the video in October 2002. June died seven months later, on May 15, 2003. Johnny died four months after June, on September 12, 2003. The tumult of their 40 years together ceased. Their human story lived on.

J.R. Cash was born in 1932, and grew up in tiny Dyess, Arkansas. He loved fishing and gospel music. His older brother, Jack, died in 1944 in a sawing accident at his work. J.R. and Jack both felt a queasy sense of doom that day; J.R. urges his brother not to go to work. But Jack did, the accident happened and he died several days later. J.R. loved his brother as a best friend and felt his loss profoundly for the rest of his life.

As a teenager, hearing J.R. singing in the house, his mother signed him up for singing lessons. Initially, they didn’t go well.

“J.R. went along grudgingly each week to see LaVanda Mae Fielder. It might have been okay if she had let him sing songs he knew, but he had to sing songs the teacher thought were good vocal exercises, such as the Irish ballad “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen.” After just three lessons, Fielder was frustrated by the teenager’s lack of progress.”16

Fielder then asked J.R. to sing a song he knew. He sang “Lovesick Blues,” by Hank Williams.

“The chance to sing one of his favorite new songs freed J.R., and his voice was so engaging, the teacher closed the lid on her piano and told him the lessons were over. He shouldn’t ever let anyone change his style, “ever,” she repeated forcefully.”17

After a stint in the U.S. Air Force, J.R. began his music career in earnest, auditioning for famed Sam Phillips of Sun Records in 1954. He quickly grew in popularity on the country charts. On stage, he became Johnny Cash, although June would call him John. By the late 1950s, with mega-hits like “Folsom Prison Blues” and “I Walk the Line,” he had become one of country music’s brightest, biggest stars.

In those days, musicians – even stars – would perform a show in a city one night, pack up their car and drive to the gig for the next night. That drive might start at 11pm or midnight, and might take 6 or 8 hours. To stay awake, the musicians would often take medicines – drugs – to keep them up. Once they arrived, they’d be wired but desperately needed sleep before that night’s show. So they’d take more drugs – this time to calm them down and put them to sleep. Add in freedom and a pretty constant soaking in alcohol, and many of them found themselves addicted before long. It could become a treacherous cycle of freaky highs and dark, melancholy lows, full of erratic and dangerous behavior.

In late 1961, June hesitated to join Johnny’s show, because she knew his reputation for wildness, drugs and infidelity. Remember, in 1961, she was still married to Rip Nix, and Johnny had a wife, Vivian, and four daughters, Rosanne, Kathy, Cindy and Tara. In 1965, Johnny was thrown out of the Grand Ole Opry after destroying some stage lights.18

Whatever hesitation and qualms June had, she and Johnny were soon together, a poorly kept secret in the gossipy Nashville music scene. The movie Walk the Line goes into this period of courtship extensively and well.

In 1966, June and Nix divorced. By early 1968, Johnny and Vivian had divorced too. On stage in London, Ontario, Canada, on February 22, 1968, Johnny proposed to June. She said yes, and they were married a week later, on March 1, 1968, in Franklin, Kentucky. Their only child together, John Carter, was born in 1970.

The oft-heard refrain about their relationship is that June saved Johnny. She fought and battled and struggled, and through the power of her love for him, and his love for her, he beat his infernal addictions. He sobered up. He turned the corner for good.

That’s the story I expected to find. I didn’t find it because it’s not true.

By the time of their marriage, the pattern of their life together had been set. Life would move along, Johnny would feel stable. Then, for any reason or no reason, his drug intake and drinking and recklessness would spike. He’d embarrass himself and the band on stage. He’d become destructive or disappear for days. He’d dig a hole that June feared would become his grave. June would step in, “fight dirty….steal [the drugs] and flush them down the commode!”19 John would explode, they’d fight, and life would become so chaotic, so anarchic, that June would threaten to leave, or might leave for a few days. Then, Johnny would repent, and varying degrees of begging and pleading would keep June around. In a few cases, the family staged interventions for Johnny, leading to stays at the Betty Ford Clinic or other addiction center. He’d come home, gentle and sweet as an angel on high – and sober-ish. One of these cycles could take months or even years, and the waves crashed upon the beach, wrecking themselves again and again, always another on the horizon, only calming as decrepitude overtook them both in their final years.

Over those 40 years together, Johnny brought more and more of their family into that vortex of addiction – several of their daughters succumbed, then their son, and, finally, for the last decade or so of her life, June.20 Johnny may not have been their candyman, but he was their example.

The story of their marriage does not end with reformation. The plane doesn’t pull out of the tailspin and fly off to a distant, bluer than true blue horizon and a cloudless life.

No, the story of their marriage involves countless tears, depression, isolation, heartache, broken dishes and windows and lights, dark memories and turmoil. Vibration is movement, not ethics or happiness.

Their story also includes forgiveness. A decade ago. A year ago. A month ago. Yesterday. Today. Tomorrow.

A never-ceasing wave of calming forgiveness, gently lapping the rocky shore.

Never-ending.

June extended forgiveness again and again, always finding deep within her heart a solid core that bad behavior, poor decisions, drugs and fear could not crack. That core gleamed forth from her heart and animated her actions during the worst of Johnny’s storms.

The marriage leaves us unsettled. An awful, beautiful, terrible, superb human romance. A mess of a human romance. Yet held together by an unbreakable chord of forgiveness.

Her forgiveness was her best virtue.

Their best virtues – and much of their music – came from Christianity. They both grew up in the way of rural American Baptism. It echoed through the hills of Poor Valley and in the dusty streets of Dyess. They both grew up singing and loving Gospel music. They didn’t learn it; they steeped in it. They may have injected, snorted and swallowed drugs, but they steeped in the Word of Jesus.

They knew and expressed their faith through song and art. And they dug in deep. They both earned doctorates from the Christian International Bible College. They joined revivals with Billy Graham. Much of Johnny’s desire to highlight the downtrodden – the concerts at Folsom and San Quentin Prisons, among much else – called to his heart from his Christianity. Jesus suffered and died as a prisoner, and Johnny found the Fountain of Living Waters of Jesus even among cutthroats, robbers and scum.

One night, June had a dream that Johnny was speaking the Gospel on a dusty Mount in the Holy Land. When he heard about the dream, John instantly felt a bolt of inspiration – he and June would film a movie based on the Gospel of Christ.

They did. They called it The Gospel Road. June played Mary Magdalene – not Mary, the Mother of God. Johnny, in his trademark black, narrated and sang. More than 50 years later, it holds together better than we might assume, given its quirky mix of Gospel music, country music and curious Gospel storytelling. It speaks especially to the stories of Christ’s temptations, His hatred of hypocrisy, and His life immersed in nature. We tell the stories we need to hear.

The movie didn’t do well. Eventually, Billy Graham bought the distribution rights so it could be shown for free in thousands of churches.21 No matter. Inspired by the love of his life, Johnny had told the Gospel story the way he wanted to. They way they wanted to share the story of Christ.

Much more popular was his rendition of “Ring of Fire” which became one of his very biggest hits. By most tellings, June wrote the song with Merle Kilgore. One version says Johnny wrote it, and came running out of the house chirping nonsense that “I just wrote this little tune and I’m gonna let June have the credit for it.”

My distinct sense is the June and Merle version is the truth. The evidence is the understanding. She appreciated the song in a more textured, halting way. Johnny’s version sings to the heat and excitement and rawness of fire and love. Listen to June’s version. She sings to the mesmerizing, but murky, alchemy of fire and love. When we look into a fire, when we live in love, we never remain the same person. And that’s the sentiment June’s singing reveals.

We live in an excitement-obsessed world, and Johnny’s version made the song famous. The mariachi band, the energy, the uniqueness of it amongst the syrup, even then, of country crooning – he combined it all to create a massive hit.

Then, as he struggled to find more hits, he lost his way. He brought the mariachi band back for “The Matador.” No dice. The song did not do well. You only get to use a trick once.

Johnny had become a parody of himself. At times he also leaned too much into the whole “Man in Black” image. Yes, he played in prisons and identified with the downtrodden. His image as the Man in Black – he’d only wear black, no color, until divisiveness had ended – struck such a chord because the downtrodden gave him that identity. They called him the Man in Black. It lost all of its force when he started calling himself “the Man in Black.” His song of that name is gawdawful. When he points out his virtues, like identifying with the distressed, it all becomes a mask he wore simply to attain the name. We no longer take it, or him, seriously.

June – for all her yucking it up on stage – never became a parody of herself. She was who she was, for good and ill, the entertainer from Poor Valley and wife of John R. Cash.

She left four pillars in her life to reflect on – music, family, Jesus, drugs. They combined in a strange, messy concoction. To the top of that mad froth rose one light, airy effervescence that could not be drowned or dissolved. The girl from Maces Spring, in a life of sublime highs and wretched lows, modeled one radiant lesson:

Forgiveness.

Thank you to Foster for the gift of Season 3, which allowed me the time and space to research June’s remarkable life. I am indebted to my Foster colleagues for their time and effort in editing Part 1 of this essay: Lyle McKeany, DJ May, Danver Chandler, Jude Klinger and Shanece Grant. Thank you, thank you!

Sources

Cash, John Carter. Anchored in Love. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, Inc., 2007.

Cash, John R. Cash: The Autobiography. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

Cash, June Carter. Among My Klediments. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1979.

Cash, June Carter. From the Heart. New York: St. Martin’s Press 1987.

Cash, Rosanne. Composed. New York: Penguin Books, 2010.

Hilburn, Robert. Johnny Cash: The Life. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013.

June Carter Cash online obituary

Cash, John R. Cash: The Autobiography. HarperCollins: New York, 1997. p. 133.

Cash, John Carter. Anchored in Love. Thomas Nelson, Inc.: Nashville, 2007. p. 11.

Ibid. p. 14.

Cash, June Carter. Among My Klediments. Zondervan Publishing House: Grand Rapids, MI. 1979. p. 19.

Cash, John Carter. p. 17.

Cash, June Carter. p. 28.

Ibid. p. 28.

Ibid. p. 28.

Cash, John Carter. p. 22.

Cash, June Carter. p. 65.

Cash, June Carter. p. 51.

Cash, John Carter. p. 36.

Ibid. p. 42.

Cash, Johnny. p. 157.

Hilburn, Robert. Johnny Cash: The Life. Little, Brown and Company: New York, 2013. p. 602.

Ibid. p. 22.

Ibid. p. 22.

Cash, John Carter, p. 48.

Cash, June Carter, p. 83.

Cash, John Carter, p. 133.

Beautiful portrait of an extraordinary life. So glad this finally made it out into the world.

Wow. Tremendously moving, and well presented, piece that illustrates a range of emotions and dives deeply into what it means to strive for improvement, to be part of the work of others, and to be married. Really loved this.