What I Read Q2 2025

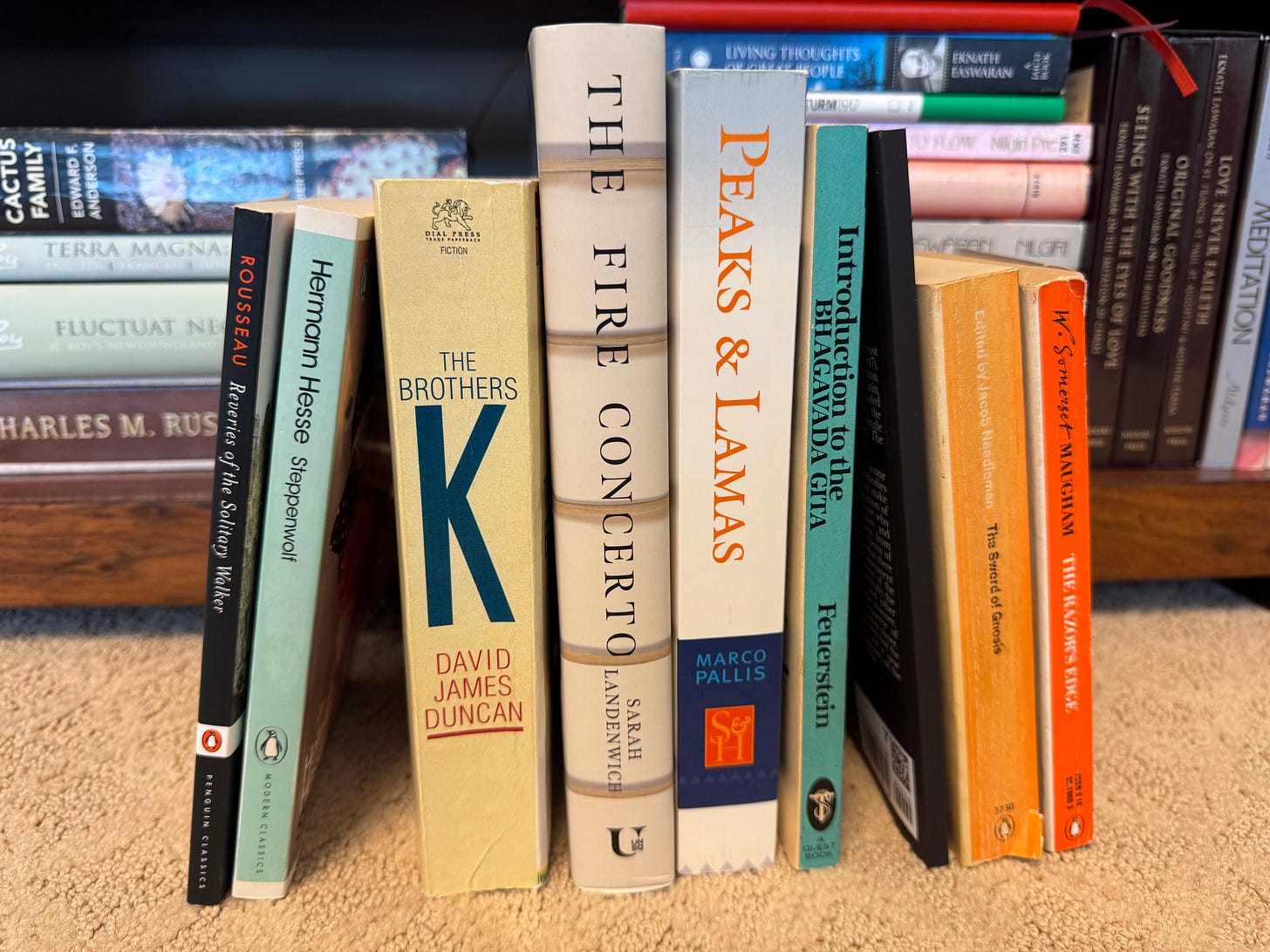

I speed through a debut novelist's tale of music and love; dig further into The Bhagavad Gita; journey to Tibet and the interior; savor novels by Hesse, Maugham and Duncan; and much more

I reveled in three wonderful months of reading. As I wrote these reviews, I kept reflecting about how many of the books I want to, and will, read again. A sure sign of a book well-chosen. My reflections for the quarter are below. Enjoy!

You can also see reviews of my first quarter reads here:

The Fire Concerto by Sarah Landenwich

This will go down as one of my very favorite books this year. I stayed up past 1:00am three nights in a row to finish the book. And let me say, I am no night owl.

The story, masterfully crafted by debut novelist Sarah Landenwich, kept me seeking more and my heart racing. What will happen next? And next? And next?

My wife, also powerfully drawn into the story, sprinted through it too.

The novel is about music, mastery, loss and renewal. Mostly, to me, it sang about love. Can we love who we were, and no longer are, and never will be again? And can we love who we are and who we might become? Can we reach out to something — or someone — to walk that tense tightrope, the weaving of past, present and future, with us? Can we love what we find inside of us, and also open our eyes in love to what we discover outside ourselves?

Beyond beautiful, I cannot recommend it highly enough!

1984 by George Orwell

In 1948, sure, this book kicked you in the teeth. By 2025, it has all come to pass, or very near. So the book has not retained its shock value. It tells far more than shows. I understand why so many people love it. But it didn’t speak to me with the same force as it did when I first read it in high school.

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

We read this for our book club. It’s funny how books affect us. The line, “But most of all…I like to watch people” reminded me of my Dad. When he visited my brother and me in Washington, DC, he and Mom would stay at the Georgetown Inn. It had a restaurant inside. Dad would spend hours in the window of that restaurant, sipping a Coke, and watching people walk by on Wisconsin Avenue.

The line, “But most of all…I like to watch people” reminded me of my Dad.

A friend mentioned that the reference to a garden brought up remembrances of his recently-deceased father, who was from Britain, and grew up amidst beautiful gardens and tended a lovely garden in his retirement too. Our friend shared a quote, from his father or grandfather, that “if you had a happy childhood, you would love retirement.” Meaning — if you had passions and hobbies and ideas and places to explore as a child, in retirement you could return to your primal loves, and find abundant happiness and contentment.

I’d never thought about life that way. For me, that comment opened up the joy in reading with others. A similar thing happened in chaplaincy. In reviewing with my colleagues a pastoral conversation from the prior week, I received insights that, had I spent 1,000 years ruminating on my experience, I never would have lighted upon. And that opened a world of inner exploration to me.

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

My favorite of the “Dystopian Trio.” Far less sketchy than 1984 and Fahrenheit 451 — a more properly full novel. All sweetness and light, all air, all pleasure and ease, and good feelings — brought to you by the brave new world.

Sometimes in books, I wonder, Where am I in this story? Who am I?

I hope to God I would have been the Savage:

“But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness, I want sin.”

Even at the terrible end, only he — the so-called Savage — keeps his head and his heart. Only he is human.

Peaks and Lamas by Marco Pallis

The book relates two of Pallis's trips to Tibet, in 1933 and 1936. He had also previously visited in 1923. We have to remember what that means — the days before the Communist takeover and amalgamation of Tibet into Greater China. Truly, one of the terrible calamities of the 20th century, an age full of atrocities.

Pallis went to Tibet not for a touristy-show. He went to understand, and to live as much as possible as a Tibetan, so that he might know.

Written in 1939 and revised in the late 1940s, Pallis writes extensively on Tibetan art, nutrition, architecture, language (which he strove mightily to learn — again, living as much as he could so that he might know their life), dress, culture, and Traditions.

I can't recall the last book in which I underlined so much, took so many margin notes and flagged so many pages. Since I read it in March, I have returned to it often for reflection and distilled wisdom. It is certainly one of my top books of the first half of 2025.

Pallis spends a great deal of writing on enumerating the key points and construct of the universe in Tibetan Buddhism. It's a marvel of clear writing about so complex a topic. He also offers incisive comparisons and points of contrast between the Traditions of Tibet and the Christianity of Europe. For instance:

"I do not believe that this compassion, said by some to be special to Buddhism, really differs in essence from its Christian counterpart; but it is....more consciously linked with a certain intellectual concept, of which it is the corollary -- a recognition of the relations that exist between all creatures, including men, based on an insight into the true nature of the universe, and not dependent on a vague emotional appeal."

Again, Pallis wanted to live in the ways of his setting:

"We had been waiting for this moment to put into execution the long-cherished plan of adopting, as far as possible, the Tibetan way of living, in regard to both food, dress, and personal habits. We wanted to absorb the spirit of the Tradition by direct experience, subjecting ourselves to its laws to the greatest possible extent; for there comes a time when it is difficult to rest satisfied with the part of the observer....I regard this living of the Tibetan life as an extension of the study of language. There is speech in gesture, even in the way a cup is lifted to the lips, in a bow, in a thousand light touches that go to reinforce the spoken word and lend it additional point. Without them, language remains a foreign thing to the last. Externals, such as clothes, count for a great deal. The actor who wishes to live the part must first convince himself."

Pallis, who wrote the Forward to Whitall Perry's Treasury of Traditional Wisdom, gives great respect to his adopted way of life and to the spiritual underpinnings of it. One that comes through is the respect shown to foreigners and to the Other: "One young lama told me that they were taught from childhood not to speak ill of other religions, but on the contrary to treat them with every respect." And about another lama he encountered: "the parables of the Gospel, in particular, appealed to our lama, nor did it ever occur to him to treat them as less authoritative because they belonged to a foreign religion."

For all the distance he traveled, across space and time and elevation, he clearly undertook an even more profound journey to the interior. He treated that journey no less carefully or seriously. He finds in this dual sojourn not merely the antidote to the sickness of his home continent, gone mad in fury and destruction then decadence, and about to do it all over again. He found the anchor of life, the real rock of grounding for people wishing to know what they might become, wondering what truly is in store for them in life. The rock he found was Tradition, and it became the bedrock of his life no less than of the Himalayas he traversed.

"One can but repeat it: a personal reintegration in an authentically traditional form, as well as "normal" participation in its attendant institutions, is an indispensable prelude to any adventure into the path of non-formal knowledge; by this means the individuality is conditioned, "tamed" as the Tibetans would say, in preparation for the supreme task that lies ahead. To those aspirants after the spiritual life who...have come to reject the modern world and its profanity, but who, as far as any positive action is concerned, waver on the threshold perplexed by doubts as to the next step to be taken, to such as these the only advice that can be offered is the traditional one: namely, that they should first put themselves to rights as regards the formal order....by regular adherence to a tradition; after which they should make use of the fullest extent of the means provided within the framework of that tradition....Lastly, if and when a call to the beyond becomes irresistible, they should place themselves under the guidance of a spiritual master, the guru....A popular proverb says: "Without the Lama you cannot obtain Deliverance."....In a literal sense this refers to a man's own spiritual director, "his Lama," who is the visible "support" of Tradition....But there is also an inner and more universal meaning inherent in "the Lama"; for behind every support there is the thing supported, which the symbol both veils and reveals. Here it indicates the divine guide whose hand sustains the climber as he strives to reach the summit of Enlightenment. Taken in this sense, the Lama, the Universal Teacher, is TRADITION ITSELF."

Hinduism and Buddhism by Ananda Coomaraswamy

Pallis, Perry and other writers in the Traditionalist school reference Coomaraswamy often. I had read about him earlier this year in The Essential Whitall Perry, but the time had come to read the man himself.

This is a short, densely-packed book. In 28 pages on Hinduism, he offers 158 footnotes, referencing sources as divergent as Plato, the Bible, the Rig Veda, the Bhagavad Gita, poetry and more. In 29 pages on Buddhism, he references 307 footnotes, similarly varied.

While I came away with a deep appreciation for Coomaraswamy's erudition and concision of expression, I feel like I barely skimmed the surface in my own understanding of his argumentation. I'd like to return to this book after another year or two of readings in Hinduism, Buddhism and Traditionalism.

The Razor’s Edge by W. Somerset Maugham

An outstanding tale of friends in the years after World War I: what they seek, and what they find, in life and death.

Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse

We read this for Book Club and it spurred a fascinating discussion. We are all in or approaching (cough, very early) middle age and we agreed those are good years to read this book profitably.

There were some translation issues. The Penguin Modern Classics version and this edition seemed the most readable. Other translations were tough to slog through, although no one read the new Penguin Classics translation that came out earlier in 2025.

Hesse himself believed this book to be the most misunderstood of his novels. Readers, he perceived, focused too much on the background of malaise prevalent in the 1920s and 1930s, when Hesse published it. Of course – World War I, the destruction of the German Empire and old order, the raging economic hardships across the world. In a short postscript, Hesse writes,

"I would nevertheless be pleased if many readers could recognize that although Steppenwolf's story is one of sickness and crisis, these do not end in death or destruction. On the contrary: they result in a cure."

Our ills and malaise appear quite different in the 20s of the 21st century. Nevertheless, I also believe the tale of the Steppenwolf offers us a cure to these troubles as well.

The Sword of Gnosis edited by Jacob Needleman

A book of essays in the Traditionalist metaphysical vein, from the pages of the now-defunct magazine Studies in Comparative Religion. Essays by Marco Pallis on "The Veil of the Temple" and "Is There Room for "Grace" in Buddhism?" highlight the collection, along with others by Frithjof Schuon, Rene Guenon, and others.

Introduction to the Bhagavad Gita by Georg Feuerstein

I am pretty much trying to read everything I can get my hands on by Feuerstein about The Bhagavad Gita. This volume focuses on the cultural backdrop of the Gita, and its underlying philosophy as a piece of the massive Mahabharata, one of the great scriptures of Hinduism and the world.

Reveries of a Solitary Walker by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

I began reading these musings in Paris. I could only get to Walk Four before Rousseau's moaning and complaining about the backstabbing world prompted me close its pages and move on with my life.

The Brothers K by David James Duncan

While I read more fiction than usual this quarter, observers of these lists of the books I have read have probably noticed that I mostly read non-fiction. Our book club doesn’t have any rules about books selected, but we’ve usually picked books of fiction. I like that. It’s good to have a gentle nudge every few weeks to put down the exegeses of theology, the what and how of history, the lessons of biography, and witness my imagination and empathy come far more alive through reading works of fiction.

Our book club read it for our June get-together. It took me about 200 pages to get into it, but staying with it was well worth it. The last 400+ pages zipped by.

The tale of four brothers, their young twin sisters, and Mom and Dad, growing up in Washington State in the 1950s and 1960s. Can the ex-rising baseball star of a Dad with a ruined thumb get another crack at the Bigs? How will the three brothers who rebel against their Mom’s rock-steady adherence to Seventh-day Adventism turn out? How will the one brother who remained, with his Mom, a believer? How will the turmoil of the 60s affect this family? Will they survive intact? Or will that hard era break them — as individuals and a family — like twigs in a tornado?

And you, you, gentle reader, how will this tale impact you? I know how it wrenched me, racing through pages, days, years, begging that this family of broken, yet good, people be spared from themselves and from their times. It was useless, I know, to pray over fictional characters. But that’s what I found myself doing. Praying for these broken, yet good, men and women.

13, 14, 15. Things Become Other Things (Fine Arts), Things Become Other Things (Random House) and Other Thing by Craig Mod

Read my reviews here:

On to Q3. Bring it!

What books did you read recently? Which ones did you love?

Which ones will you read again?

I’d love to hear from you!

Love your lists! You inspired me to start keeping a list of my own - which reads like a deep dive into all aspects of Horror - which it is. I prefer to think of this as research into a genre. I've added The Fire Concerto to my To Read list!

I read Steppenwolf in 6th grade English class...maybe I should read it again?!!

That's an impressive quarter, Russell! I always enjoy seeing what my friends are reading.