What I Read Q1 2025

Sherlock Holmes; on Japanese Folk Crafts; Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance; a Unique "Gospel"; on Yoga and Traditionalism

A short note before we get to the issue. If you’re enjoying the essays and podcast on Solvitur Ambulando, I invite you to Pledge Your Support of this work and vision. Solvitur Ambulando is free to enjoy and I have no intention of turning on paid subscriptions anytime soon. (If that changes, I will give pledgers plenty of notice.) But knowing you savor the fruits of my efforts — to the tune of being willing to put some of your hard-earned ducats toward it — would mean, well, more than you can possibly know. Thank you for considering, and for reading this labor of profound joy in my life.

The Kingston Trio, a terrific folk band of the 1950s and 1960s, which my Dad loved and got my brother and me into, ended their 1958 live set at the Hungry I:

“And now, in response to a diminishing number of requests, we’d like to bring this number forward.”

Similarly, in the years I have written my reviews of the books I read that year (2022, 2023 and 2024), not once has a reader reached out to say, “Russell, I dig these annual reviews, but I don’t want to wait a full year to see what you’ve read! Give ‘em to us sooner!”

Nonetheless, like The Kingston Trio on that cool San Francisco evening sensing the audience’s fervent, shaking need for “When the Saints Go Marching In,” I too can detect the subterranean purr — nay, a veritable quaking — of my readers’ unspoken desire for more timely updates on my reading adventures.

And so, my friends, let this pilgrimage, as it were, of saints and sinners, set off.

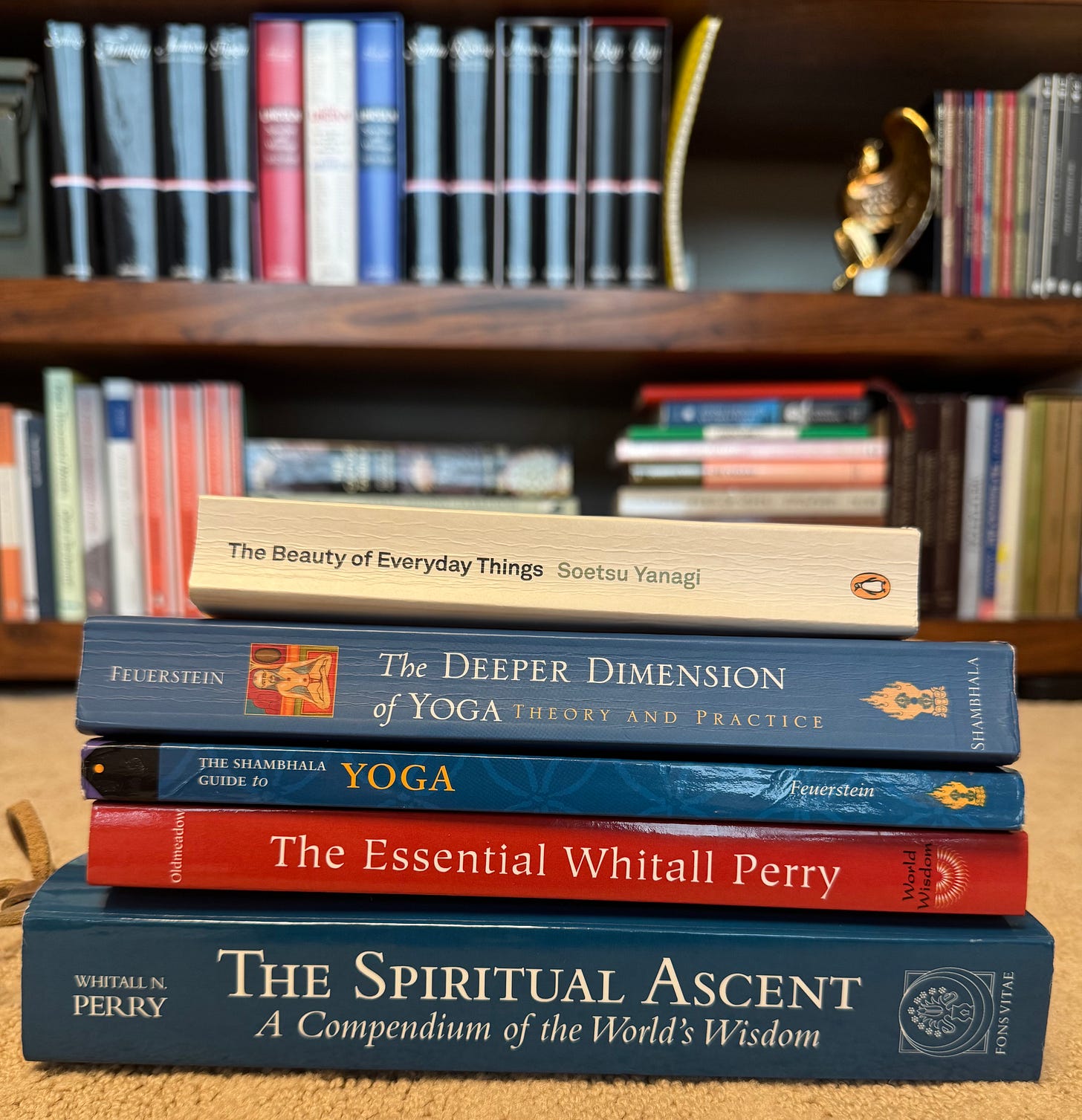

The Beauty of Everyday Things by Soetsu Yanagi

Soetsu Yanagi became dissatisfied with how Japan modernized in the early 20th century and abandoned its ancient folk crafts. By folk crafts, he meant items used every day by much of the population, and that therefore were created at some scale. Not industrial scale, but he was not interested in delicate, do-not-touch-this-single-piece-of-art items. For example, he admired folk made teapots and tea cups, Buddha statues and other devotional objects, vases, and kimonos.

“Utilitarian crafts have been looked down on as something of a lower rank. As a result, our aesthetic sense has been severely impaired owing to the fact that beauty and life are treated as separate realms of being. Beauty is no longer viewed as an indispensable part of our daily lives…[T]here is no greater opportunity for appreciating beauty than through its use in our daily lives….It was the tea masters who first recognized this fact.”

He sought to reclaim that folk craft tradition – through his speeches and writings, and through founding the Japan Folk Crafts Museum in Tokyo. I suspect his efforts are a major reason so many beautiful, useful objects come from Japan today: pens, notebooks, matcha bowls and much more.

One of my favorite passages:

“It is one of the mysteries of the world that such great beauty should be found in such lowly objects: that they should come from uneducated hands, that they should originate in remote provincial areas, that they should be the most common type of everyday object, that they should be used in dimly lit out-of-the-way rooms, that they should be uncolorful and made of the poorest materials, and that they should be produced in great numbers and at low prices. What a mystery it is that the god of creativity should reside in the hearts of these ingenuous artisans possessing no artistic ambition, without intellectual pride, soft-spoken, and happy to be leading poor but honest lives. These same qualities are vividly apparent in the objects themselves.”

Lamb by Christopher Moore

My friend Jude Klinger introduced me to “The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal.” A bestseller when it came out in 2002, it is certainly irreverent. And yet it contains a certain reverence as well.

Easwaran Inspirations by Eknath Easwaran

Eknath Easwaran came to America from India in 1959. Two years later, he established the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation in California. For the next four decades, he taught a form of meditation he called Passage Meditation, which fit into his Eight-Point Program. This set of 6 short e-books, taken from Easwaran’s innumerable talks, speeches and writings, goes into some of his most vital themes: meditation; finding true happiness; coming to terms with aging and the inevitability of death; and learning to truly love.

Every time I read or listen to any of Easwaran’s messages, I find a wellspring of encouragement to become the man I am meant to be. And a subtle, prodding love, that no matter how little progress, how small the steps, how arduous the journey, I am making advances – and I can make more. Great inspiration indeed.

The Penguin Complete Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

I had to go back. I had to go back to the beginning – the start of my reading journey. Before kids and work. Before college. I had to return to the early days of high school, when I read only for fun. Not for learning or self-improvement or mastery or illumination. Simply, and only, for enjoyment.

At age 15, I read my Dad’s copy of The Complete Sherlock Holmes. I fell in love.

With Sherlock? Well, maybe. Yes, perhaps I did go through a phase when I wished I could smoke a calabash pipe. And rock this sweet Holmes cap. No, it was more. I fell in love with the stories. With Conan Doyle’s language. With the world he created.

Sherlock Holmes may have been a man; in an alternate universe such an eccentric figure doesn’t seem hard to imagine. But if he had existed, surely he made a potent impact against crime in one small country, in one short time period - not even a quarter-century.

Sherlock by himself? A man. An impressive one to be certain. But at the end of it all, simply, and only, a man.

Sherlock with his partner Watson?

A legend.

The Wisdom of Yoga by Stephen Cope

Another Stephen Cope book I loved. This book provides his unique exegesis of The Yoga-Sutra of Patanjali, who likely lived sometime around the second or third century CE:

“Patanjali views every aspect of living as an opportunity for practicing wisdom. He is concerned with how we think and act, how we breathe, move, sleep, dream, and speak. Every aspect of our motivation, cognition, and behavior is of interest to Patanjali – and he harnesses them all as part of the path of yoga.”

Cope takes the reader through some of the thorniest problems of modern life - our non-stop racing minds; the discomfort with actual feelings; struggles with meaning; to-do lists reaching toward infinity; things we consume and that consume us; accurate self-assessment; and seeking holistic community; among others. He then applies Patanjali’s lessons from yoga to this grappling.

“Yoga should come with a warning: these practices will change your life. The deepest desires of our Managers, and our other subpersonalities, will be shot to hell. But the outcomes will be more spectacular than we can possibly imagine.”

To end the book, Cope analyzes some commonalities between yoga and Buddhism, and some key differences. He also includes Chip Hartranft’s English translation of the full Yoga-Sutra of Patanjali.

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig

My friend Sean has been recommending this book to me for 30 years. But I didn’t read it until another friend started a book club, with it as the first book.

My short, short review: Glad I read it. Won’t read it again. Not the fish I’m frying in life.

The Essential Whitall Perry edited by Harry Oldmeadow

In an enormous labor of love, Perry compiled, organized and provided commentary for A Treasury of Traditional Wisdom (now titled The Spiritual Ascent: A Compendium of the World’s Wisdom). At the suggestion of Ananda Coomaraswamy, Perry undertook the task of amassing the Treasury – an effort that took 17 years. It’s an incredible book and stunning achievement, with quotes from the world’s great religions and spiritual traditions carefully organized and cross-referenced. I read a page or two each day, and I may not finish the book in 2026. Very much worth picking up a copy.

Through the Treasury, I became intrigued with Perry, Coomaraswamy, and other Perennialists – who hold the view that the ancient traditions of the world all share common wisdom and truth. (The best-known articulation of this view is Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy, about whom more below.)

The Essential Whitall Perry contains some of Perry’s most incisive essays. He doesn’t pull any punches. In discussing Western Christianity, he writes,

“the Promethean humanism of the Renaissance brought a mortal scission, sundering the Inward from the Outward, Spirit from Cosmos, Church from State. Christianity was thenceforth to be an affair of the churches and monasteries, with the rest of life more or less abandoned to a relativistic individualism that would with its analytical thought and experimental sciences explore the properties of a matter now sealed off from higher orders of Reality, thus leading to pursuits in every facet of society that were irremediably profane…”

He shares warnings about the dangers of the East too:

“In these degenerate times which have spawned countless pseudo religions, often Oriental in stripe, the Adversary wears as many disguises, and it seems to be arch-rare when anyone can distinguish the gulf which separates authentic teachings from the distortions made of them by people like Madame Blavatsky, Krishnamurti, Aurobindo, Gurdjieff and others…”

While the aforementioned Aldous Huxley may have claimed to swim in the stream of Perennialism or Traditionalism, Whitall seems dubious of his approach to the ecstatic state through hypnosis and drug use. In his essay “Drug-Induced Mysticism: The Mescalin Hypothesis,” Whitall enlists Plato, Meister Eckhart, St. Thomas Aquinas, and other mystics to take a battering ram Huxley’s claims about his consciousness change. I have not read Huxley (or taken mescalin), so I can’t argue with authority here. But my eyebrows pricked up as I read his view that what Huxley did and wrote about (and what Michael Pollian wrote about and what thousands of people do today) is fundamentally and qualitatively divergent from primordial mystical understanding. My eyebrows also pricked up when I did not see any Native American sources noted in the essay.

Whitall writes most impressively in the stories of his encounters with the giants of Traditionalism: Coomaraswamy, René Guénon, and Frithjof Schuon. For instance,

“Whereas the Doctor [Ananda Coomaraswamy] had openly encouraged us to go to India, even generously intervening in the matter of visas – which supposedly would be reaching Cairo any day now from New Delhi – the French metaphysician [René Guénon] by contrast made it clear through subtle innuendo that Hinduism was off bounds. Yet all he said was: (1) that things had greatly degenerated in India in recent years, and particularly since the War [World War II]; (2) that Hinduism is a vastly complex structure with numerous pitfalls for the unwary, among which were false gurus; and (3) that it would be nearly impossible for a Westerner to have the discernment and criteria necessary for distinguishing the wheat from the chaff in an East that often operates by standards other than those to which an Occidental is accustomed.”

And on Schuon,

“Schuon taught that travel in someone spiritually inclined, when done for legitimate purposes, can sharpen the faculties of the soul through the contact one has with unfamiliar scenes and the challenges of situations not met with at home. He himself on these occasions was always alert, punctual, disciplined, and keenly observant. He had ever present a small notebook for recording ideas or sketching faces of marked interest, or for composing diagrams dileating metaphysical and cosmological conceptions.”

But I felt most drawn to Coomaraswamy, and Perry’s descriptions and analysis of the man:

“Not only was the Doctor’s erudition on a purely human plane staggering in its combination of scope, depth,and universality, with a literary style to match, but he was also a skilled polemicist, a brilliant conversationalist, and a man of unfailing generosity towards aspiring students and all who turned to him for help….There seemed no pause in his concentration….[h]e felt the need of getting his work done, perhaps at the risk of a shorter life. He was by no means unaware of what he was about.”

Yet for all the beauty of Coomaraswamy’s soul, he himself felt curious humility about his efforts: “he once told us: “I shall feel happy if my writings have really been of help to four or five people….””

May Whitall Perry and his friends garner far, far more readers in the days to come.

The Shambhala Guide to Yoga by Georg Feuerstein

Now titled The Path to Yoga, this book represents Feuerstein’s shallowest dive into the world and practice of yoga. Examining some dozen topics, such as branches of yoga, the importance of a teacher or guru for spiritual growth, the moral foundations of yoga, diet, breath, concentration as the cornerstone of meditation, mantras and sounds as ways into the divine, and yoga in today’s world. He concludes his overview of yoga:

“There is no doubt that our world is in dire need of the nectar of wisdom flowing from those who have transcended the ego-personality and realized the Self and whose only concern is the enlightenment of others. The drone of our technological civilization has largely deafened us to their voices. But they continue to gift us with their wisdom and their spiritual presence. All we need to do to benefit from their incessant transmission of light is to become quiet and listen to our own hearts. There is where Yoga begins, unfolds, and fulfills itself.”

The Deeper Dimension of Yoga by Georg Feuerstein

For students interested in going deeper into yoga, this book is Feuerstein’s mid-depth analysis. (His very detailed look is contained in The Yoga Tradition.) Feuerstein was born in Germany, studied in the UK, and lived for many years in the United States, before moving to Canada, where he died in 2012. And so he constitutes an example to question René Guénon’s worries – noted above – about Westerners adopting Eastern spiritual traditions. Indeed, Feuerstein seems by all accounts to have genuinely and sincerely dedicated his life to the theory and practice of yoga. As Feuerstein himself writes near the beginning:

“To fulfill itself, knowledge must find expression in the body.”

This – this seemingly small message – reverberates throughout the book. It is the message that keeps vibrating through me too.

(This article contains Amazon Affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.)

Thanks for these recommendations, Russell! Just added The Beauty of Everyday Things to my next order of books. Can’t wait to dive in.