The Dangers of Undervaluing Reality

Thucydides and Hermann Hesse have warned us

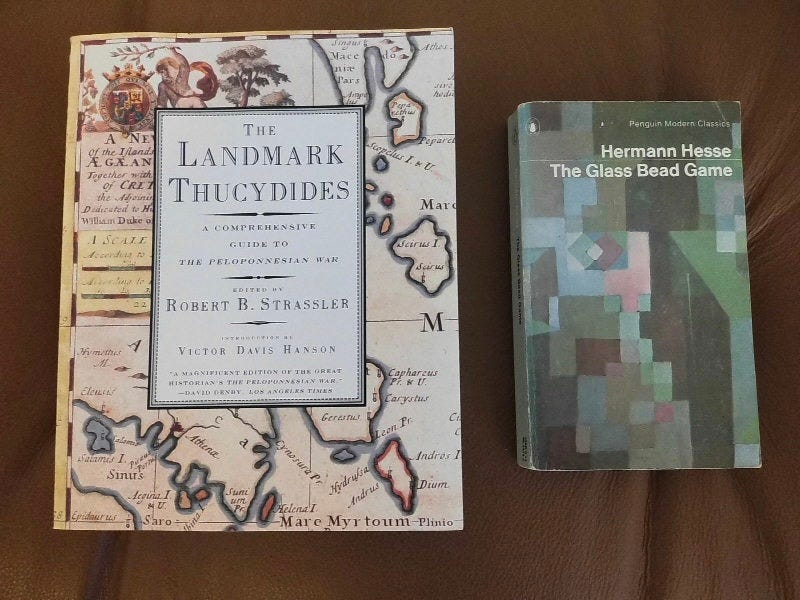

More than 2,350 years after Thucydides wrote The History of the Peloponnesian War, Hermann Hesse published his masterpiece, The Glass Bead Game, for which he won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Profoundly different books – one often considered the first true history, the other a work of a fervent imaginative mind. The History of the Peloponnesian War concerns a grave conflict between the two powers of ancient Greece, Sparta and Athens. The Glass Bead Game takes place amidst a fictional region but largely concerning the inner evolution of one man, the Magister Ludi of the Glass Bead Game, Joseph Knecht. And yet for all the differences, both books contain a central, urgent warning: ignoring or underappreciating reality can lead to devastating consequences, for the polis and for the person.

In the summer of 413 BCE —or nearly 19 years into the Peloponnesian War—Athens hired some Thracians to join its attack on Sicily, but they arrived late. Facing a crunch on its finances, Athens instructed the Thracians to head home, but to cause whatever mischief they could to Sparta’s allies on the way. They “first landed at Tanagra and hastily snatched some booty.”1 Then the Thracians came to Mycalessus:

“[A]t daybreak [the Thracians] assaulted and took the city, which is not a large one; the inhabitants being off their guard and not expecting that anyone would ever come up so far from the sea to molest them, the wall being too weak, and in some places having tumbled down, while in others it had not been built to any height, and the gates also being left open through their feeling of security.”2 [Emphasis mine]

Remarkable words from Thucydides and almost unfathomable negligence by the leaders of Mycalessus. The Peloponnesian War had raged since 431 BCE. Mycalessus did not believe they would be attacked by sea, but the city lay less than 50 miles from Athens, and not separated by the most rugged terrain in Greece. Sparta and its allies were in Attica summer after summer, then season after season, even closer to Mycalessus. Nearly the whole of Greece was at war and yet Mycalessus took almost no precautions. As quoted above, Mycalessus did not build a protective wall in many places, and in others the existing wall had fallen into disrepair. And on the day of the attack, the gates to the city were open – profound dereliction of even the most basic measures for civic protection.

Why was Mycalessus so ill-prepared? Or, what about their philosophy or culture led to this defensive disregard? Thucydides does not answer directly, but he perhaps hints at an answer – or his answer: “in particular they attacked a boys’ school, the largest there was in the place, into which the children had just gone.”3 Thucydides did not specify what he refers to when he wrote “in the place.” The two most likely interpretations seem to be “in Mycalessus” or “in Greece.” If he means “in Mycalessus,” it would indicate Mycalessus contained multiple boys’ schools – a curious fact for such a small city. If Thucydides meant “the largest boys’ school in Greece,” that would also be a curious detail – it would mean this tiny city supported the largest boys’ school in all of Greece. However, in either interpretation, Thucydides points to Mycalessus having an outsized partiality for education as the reason, or a cause, for its indifference to its defense, even amidst nearly two decades of war around it.

Thucydides wrote pointedly and poignantly about the results:

“The Thracians bursting into Mycalessus sacked the houses and the temples, and butchered the inhabitants, sparing neither youth nor old age but killing all they fell in with, one after the other, children and women, and even beasts of burden, and whatever other living creature they saw; the Thracian people, like the bloodiest of the barbarians, being ever most murderous when it has nothing to fear. Everywhere confusion reigned and death in all its shapes.”4

And the boys’ school? The Thracians “massacred them all.”5

Thucydides ended his telling of Mycalessus with haunting language:

“The Mycalessians lost a large proportion of their population….In short, the disaster falling upon the whole city was unsurpassed in magnitude, and unapproached by any in suddenness and horror….Mycalessus thus experienced a calamity, for its extent, as lamentable as any that happened in the war.”6

Mycalessus effectively ceased to exist. Even today, no one knows exactly where the city sat in ancient times. To repeat: “the inhabitants being off their guard and not expecting that anyone would ever come up so far from the sea to molest them.”7 In turning a blind eye to a long-standing nearby war, Mycalessus serves as an intense warning about the dire implications of a polis ignoring reality.

Over two millennia later, Hermann Hesse dove into the question of confronting reality, this time for an individual. Joseph Knecht became the Magister Ludi – the preeminent player and scholar of the Glass Bead Game, an elegant and esoteric game based on music and developed over centuries. The great players of the Glass Bead Game live monastic, protected lives in Castalia, with little interaction with the outside world, with reality. Knecht did have some engagement with the outside world and several years into his tenure as Magister Ludi, in his 40s, wished to leave the Order and enter the world.

Unlike the Mycalessians, Knecht acknowledged the dangers of that outside world:

“What I am seeking is not so much idle curiosity or of a hankering for worldly life, but experience without reservations. I do not want to go out into the world with insurance in my pocket, in case I am disappointed….I crave risk, difficulty, and danger; I am hungry for reality, for tasks and deeds, and also for deprivations and suffering.”8

And so Knecht left the serenity of the Castalian Order. He planned to tutor the son of a friend, and upon departing Castalia, he traveled to their home. He arose the next morning, went outside, and beheld a small lake perched beneath the hard, stony mountains. Hesse carefully constructs the scene; Knecht possesses an awareness of the power of this new-to-him reality:

“he felt the ponderousness, the coolness and dignified strangeness of this mountain world, which does not meet men halfway, does not invite them, scarcely tolerates them. And it seemed to him strange and significant that his first step into the freedom of life in the world should have led him to this very place.”9

Tito, the boy he would tutor, appeared. After enacting an impromptu almost-dance or ritual-bowing to the grandeur of the nature surrounding them, Tito suggested the two swim to the other side of the lake to experience the coming sunrise at that shore. Tito dove in and swiftly swam away. Again, Knecht felt an unease about this reality surrounding him:

“Both air and water were much too cool, and after his night of semi-illness, swimming would probably do him no good….It was true that his feeling of weakness and uncertainty, incurred by the rapid ascent into the mountains, warned him to be careful.”10

Knecht wavered, “but perhaps this indisposition could be soonest routed by forcing matters and meeting it head-on. The summons [to follow Tito] was stronger than the warning, his will stronger than his instinct.”11

Again, Hesse wants the reader to realize Knecht possessed a modicum of appreciation about the dangers of his new reality, of the rawness and terribleness of nature in this case. But what apprehension he grasped was not sufficient:

“The lake, fed by glacial waters…received him with an icy cold, slashing in its enmity, He had steeled himself for a thorough chilling, but not for this fierce cold which seemed to surround him with leaping flames and after a moment of fiery burning began to penetrate rapidly into him.”12

The end came quickly:

“he…believed he…was fighting for the boy’s respect and comradeship, for his soul – when he was already fighting with Death, who had thrown him and was now holding him in a wrestler’s grip. Fighting with all his strength, Knecht held him off as long as his heart continued to beat.”13

Yes, Knecht appreciated the uncertainty of the reality of his new life. He realized it held danger; indeed, he sought danger. But he did not appreciate the unrelenting harshness of the reality of the outside world enough. He was not cautious enough. Barely a day after departing Castalia, he was dead.

Like Thucydides, Hesse links Knecht’s insufficient appreciation of the awfulness of reality with an overzealous pursuit of education, with an academic and erudite withdrawal from the truth of the world. Hesse spends most of the book building up the Glass Bead Game, its superlative players around the world, especially in the enclave of Castalia, as a near-monastic order. The player dedicated their lives to education and growth in the Game and of their studies. Each Castalian became “like a hermit, cultivating….peace of soul and preserving a calm, meditative state of mind.”14

As exemplified by Knecht, when that calm, meditative state of mind brushed up against outside reality, the world simply and unflinchingly crushed the Glass Bead Game Master.

Could Castalia learn from the tragedies of Mycalessus and Knecht? How much appreciation of danger is sufficient to protect the person and the polis from the cold reality of the world and ensure survival? Thucydides, in more than 600 modern pages, and Hesse, in more than 500, remain eerily silent on those questions.

Strassler, Robert B., editor. The Landmark Thucydides. Translated by Richard Crawley. New York: Free Press. 1996. p. 443.

Ibid., pp. 443-444.

Ibid., p. 444.

Ibid., p. 444.

Ibid., p. 444.

Ibid., pp. 443-444.

Ibid., p. 444.

Hesse, Hermann. The Glass Bead Game (Magister Ludi). Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. Middlesex: Penguin Books. 1943. p. 363.

Ibid., p. 390.

Ibid., p. 394.

Ibid. p. 394.

Ibid., p. 394.

Ibid., p. 394.

I love reading these … brings ideas and historical facts into my awareness. And reality.

Really insightful connection. What I take away is not necessarily an overall "overvaluing" of "education," but a narrow and rigid sense of what one should be "educated" about.

It's interesting to think of today when, at once, our society 1) discards "education" in domains that don't happen inside a college, and 2) within the same colleges, has begun to undervalue the importance of education in that same very humanities/spiritual/philosophical domain that your cases seemed to have been over-fixated on.