What Do Dwight Eisenhower, Frank Lloyd Wright, Maya Angelou and Ray Kroc Have in Common?

Second Act -- Henry Oliver's book on "late bloomers" -- comes out in the US today

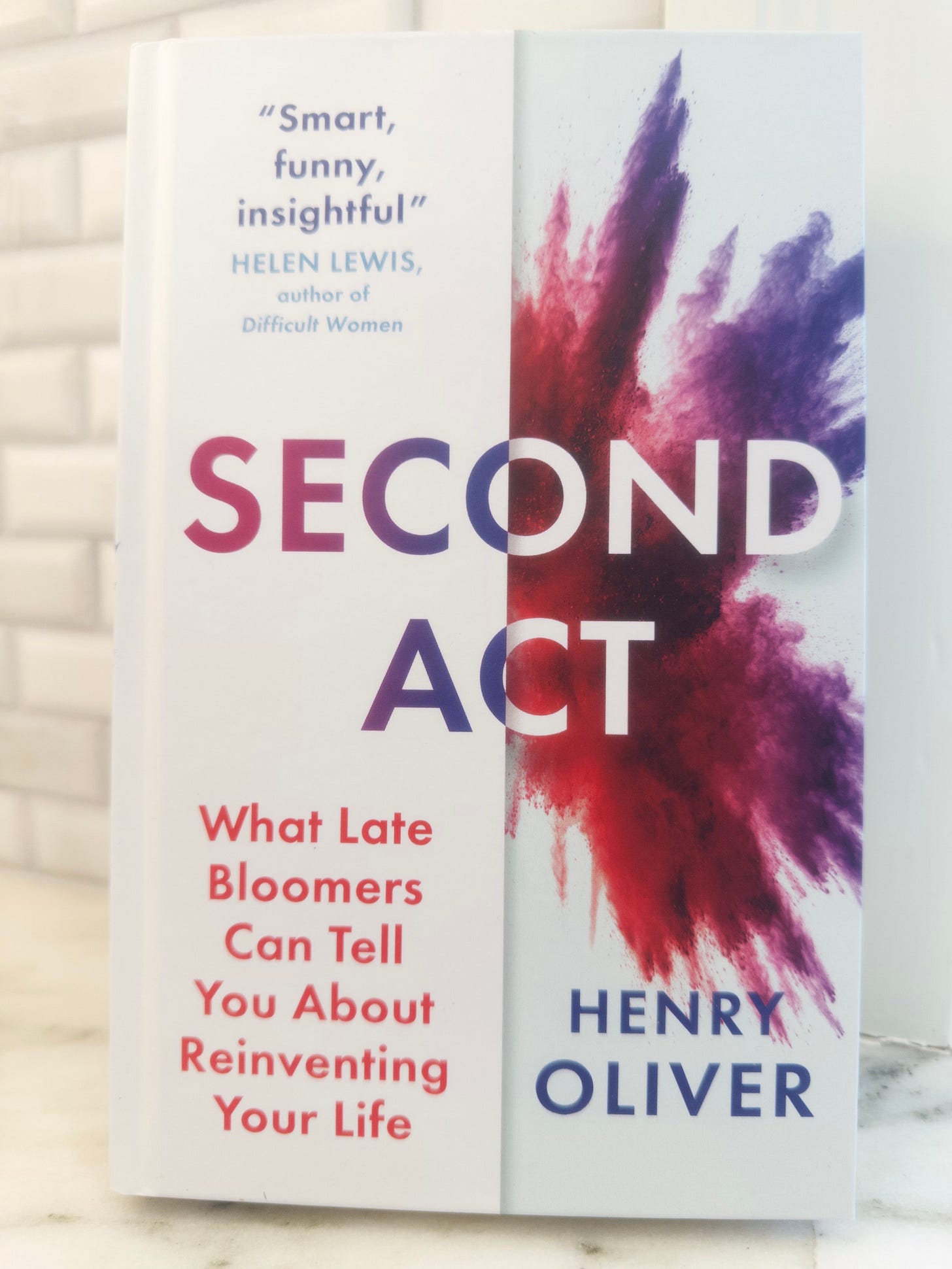

A few months ago, I interviewed Henry Oliver about his book, Second Act, which is my book of the year. The book come out in the US today. I cannot recommend it highly enough. You can order it from Amazon, Barnes & Noble or your local bookshop. My copy is en route.

Second Act offers wonderful in-depth biographies and analyses of late blooming luminaries like Katharine Graham, Maya Angelou, Chris Gardner, Samuel Johnson, Ray Kroc, Margaret Thatcher, Frank Lloyd Wright and others. He also delves into less-heralded but no less instructive personalities, such as Audrey Sutherland, who began her solo kayaking adventures of the Arctic after age 60. It also includes shorter, snippet-like lessons from Grandma Moses, Dwight Eisenhower, Winston Churchill, Vera Wang, Norman Maclean, and many others.

(Alas, Henry had to cut a chapter on Dwight Eisenhower. Here it is. Pair it with my biography of General Fox Conner, Eisenhower’s great mentor, and my interview with Steven Rabalais, who wrote the best biography of Conner.)

During our interview, Henry’s revelations about the commonalities among the late bloomers and features unique to one fascinated me. Like the book, I learned so much from Henry’s wisdom during our discussion.

In honor of Second Act being available in the US today, my interview with Henry is republished below. Enjoy. Thank you, Henry, and congrats on a wonderful, extremely insightful and useful book.

Tell me about the origin of the book? How did you come up with the idea for this book? Also, how did you meet Tyler Cowen and get connected with the Emergent Ventures grants?

My day job was in marketing, but we did not do advertising for chocolate bars or trainers or white goods. We did advertising for employment. All major companies, organizations, even mid-level places, have an advertising agency for their products and services. And then another one for their jobs. You have to go out to market and appeal to candidates and explain to people: “Why is this a good culture? Why is this a good place to work?” I was the research guy thinking about “Where is the talent? Where's the audience for these jobs? What's going on in the labor market?”

And I was increasingly seeing people in the 50-plus bracket being available, but not being chased by corporations. Then I got ill, and I took some time off work. I was doing a lot of reading of Penelope Fitzgerald, who is a novelist I really love. I was just thinking about her and her life. I read the biography and the letters, all of it. This started bouncing backwards and forwards with going back to work. I was thinking about the changing structure of the labor market and the idea that actually you don't always know how much potential someone has. Fitzgerald wrote her first serious novel when she was 60, and no one really expected it, right?

I became really interested in this topic. And I realized that my clients were not interested in it. The idea of a late bloomer was simply not on the radar for these organizations. You can come back to the labor force if you're a mother and you've been out of the labor force for five or six years. Organizations are desperate to appeal to you, and to reform their recruitment process for you. Because this is obvious talent that is finding it really difficult to come back into the labor force. But if you're a 55-year-old, and I'm saying, “hey, this person could have a whole new career,” organizations are not open to that.

Then I heard Tyler Cowan on a podcast say the phrase, “people who haven't done anything yet, but maybe they will.” And I was like, “Oh, that's it.” That's what I've been noodling on. I started blogging about it. One of my friends said to me, “this is a real thing that you're blogging about.” Then separately, it got to the point where I wanted to quit my job. And I thought, “to hell with it, I'll apply for an Emergent Ventures grant and see what happens.” And I got it. And I wrote the book. It's a long story, but I do think ideas often come out of there being a light bulb moment after a whole load of murky, fuzzy kind of stuff.

You say in the book it's difficult to spot late bloomers before they emerge. Why is that? Is there anything that can be done to spot them in advance? And do they detect themselves? Do they feel they have something inside themselves?

Well, I'm going to start with that last question. I don't think they always do. Some of them do, for sure. I don't know even if what I'm about to say is true. I think to some extent the poet always knows that they are a poet. Now that's obviously not literally true, because there are poets like Edward Thomas, who had to be told by Robert Frost: “you must write poetry.” But some people know that they have something in them, I think. But there are lots of late bloomers for whom that's not true, depending on their circumstances.

Katharine Graham, who I start the book with, had lost her confidence through years of her mother, and then her husband, essentially bullying her. That really did get in the way of how she thought about herself and what she was going to do. But it's very notable that at the crucial moment her husband killed himself, and she inherited the paper – which had been her father's paper, her family's paper – everyone said, “Well you should sell it. You should not run it.” And she said, “To hell with that. I'm not going to be the one who sells the family paper.” She had this great reserve of courage. When she wrote her autobiography, she looked back and she realized that her father had believed in her and supported her. Now, he was long dead by this point, so it was kind of there, but her courage had been squashed down by her mother and husband for years and years. Even the fact that she was quite patrician and privileged – even all that had been knocked out of her. So, I think it varies a lot depending on your circumstances and what's happening in your life.

We have this problem with the books in the nonfiction section called “Smart Thinking.” They present some great rule as if “This Is The Way Things Are. This Is Some Solution.” Psychology tells you that “This Is True,” right? But sometimes what actually happens would be a more accurate way of describing this phenomenon. With late bloomers, I didn’t want to sell you some grand theory that they're all the same. There are some core connections between them, such as having a secret life, or they’re quietly very persistent about their work. Or, often the trigger point for them becoming a late bloomer is some change in their circumstances: a midlife crisis or some opportunity comes through their network.

But they are individuals. We should spend more time thinking, not just about the averages we see when we measure them. Those averages are important and indicative. But we should also be thinking about the deviation from the average. And my contention is, basically, I don't think we pay any attention to these late bloomers who deviate from the average. We really don’t know how many there are or could be. Why don't we try to find more of these people? Because if we got, say, two more of Katalin Kariko – the woman who did so much mRNA research that was so crucial during Covid – what would the world be like? Great. Fantastic.

So, I'm always reluctant to average answers about late bloomers. Yes, they do have secret lives. Yes, it’s instructive to examine what they persist at. Don't think about what persistently happens to them, because that is the wrong indicator. Rather, look at: “What do they persist at? Do they have it?”

When you say, “Look at what they persist at,” what do you mean?

Let’s look at Margaret Thatcher. If you take an external view of her career, which is what most of her political colleagues were doing, you would see a woman who got elected to Parliament, held a couple of junior ministerial roles and then was put into the Cabinet because they had to have a woman, because otherwise they would look sexist. They thought: “We have to have a woman; it’s statutory. We’ll give her the education post, because that’s a feminine post.” They did not respect her. They did not. They were not interested in her. They thought she was a real pain in the ass and she was going to be difficult.

So, the external view of Margaret Thatcher’s career is: she's done great. She's one of a kind – one of the small number of women that's been elected in Parliament. But really no one is thinking that. No one is saying, “Oh, my goodness, Margaret Thatcher's going places.” No, no one is thinking she'd be Prime Minister.

Now, a couple people did get behind that appearance, and were not bound up with her being screechy and irritating and right-wing. And they’re saying, “Actually, you know what? She's energetic. She's decisive. She's got integrity.” A few people are actually seeing these kinds of leadership qualities.

Someone from the American Embassy arranged for her to go to Washington and meet people. He believed she had talent, was the new talent in the House of Commons, and that the Americans should make a note of her. It's notable to me that the one person who truly saw her abilities was outside of the English system. He was not blinkered. He was going around meeting people and thought she had a lot of energy compared to some others in Parliament. “What a decisive woman this is, my goodness!” And that's the real clue to what Margaret Thatcher was capable of. Whether people love or hate her, they always say she is indefatigable, she is relentless. She could do 10 hours a day of paperwork and not be tired. She does 10 years of that. She’s constantly scuttling around Whitehall trying to change things. This guy from the Embassy, he got a little glimpse into the secret life of Margaret Thatcher. He didn't know the whole story, but she was there.

She was sitting up at night obsessed with politics – reading, making notes. There's a wonderful story that she was reading the official biography of Winston Churchill. I'm sure many of your listeners-readers will know about it – it’s huge. Many volumes. Each time a new volume was issued, it had a companion volume of supporting documents. You have the narrative book, and the companion volume of government papers. Obviously, most people read only the narrative. Most people are not leafing through 800 pages of documents. But, Margaret Thatcher wrote to the biographer saying, “I found this footnote in the documents volume that mentions a speech Churchill was drafting. Do you have a copy of the draft?”

With Margaret Thatcher, that's who you're dealing with: a woman who goes home in the evening, and she's deep in the footnotes of the documents volume of this biography. It’s difficult for her colleagues to know that she's like that, because they're predisposed to see her as the irritating woman or the right-wing woman.

You're never going to make a proper assessment of her capability. To spot late bloomers, you need the ability to be the outsider and see someone and their qualities, rather than overfitting what you know about them into the patterns you're already used to seeing.

This is amazing, Henry, thank you. In your introduction, you talk about characteristics of late bloomers – Persistence, Earnestness, Quiet. You just talked about being persistent. And you hit on earnestness too. Tell me more about those three characteristics, and how they show up in late bloomers: Persistence, Earnestness, Quiet.

Let's look at Penelope Fitzgerald, the novelist. She was born into the upper class establishment in England. Both grandfathers were bishops. She was born in the middle of the First World War, so it still means something that they’re bishops. She was born in the Bishop’s Palace in Lincoln. She's born into this kind of significant family and they're a very intellectual family. Her father edited Punch, which was one of the major magazines. Her uncles are the Knox Brothers: one is code breaking at Bletchley Park in the war, another is a famous detective novelist, one is a Bible scholar, and one is a biographer. They're all writers. And you know what I mean: she’s born into this kind of cultural milieu, the last of the great Victorian tradition. That and the family are feminists. Her mother studied at Somerville College, Oxford, for instance. So she's born into a family of very high expectations.

Fitzgerald goes to Oxford, and she does very, very well. Then she goes to London and writes reviews for the Times Literary Supplement. Then she works at the BBC. But then she doesn't become a writer. Now there's this whole debate about why that is. Let’s put that to one side and look at the question of people coming from intellectual families. They get great education, they go to big cities like London. They’re among journalists and writers and all the right sort of people. And they do great. And Penelope Fitzgerald does great – but not initially. Not for a long time. Why? What’s the difference with her?

The first difference is that she lived an extraordinarily difficult life. Her houseboat sank. Her husband was an alcoholic. They had to leave London because of their creditors. Obviously, nobody wants this to happen to them, but she’s given the material to write. She had stories.

The second thing is all through her life she's learning. She’s learning languages, she’s traveling, she’s going to the opera, getting very cheap tickets, she’s reading. When she becomes a teacher, she really rereads the whole of the European tradition. She goes into really close detail. How does Jane Austen do it? Not: “What is she doing? What are the themes?” Or this kind of rubbish. She is taking a very detailed look: “How does Austen do it? What are the techniques?” She spends years doing this.

Her novels are very historical. They're very much rooted in fact – both of her own life and of historical research. They're very European. In a funny way, she is the most European of the 20th century English novelists. She set her novels in Russia and Germany, these kinds of places. And one critic, I really love this phrase, talked about “the Russianness and the Germanness” of her novels. How does she make it so German?

It’s because she spent 30 years learning German, traveling to Germany, watching operas and reading German novels in German. She possesses an amazing dedication to the intellectual life and to the life of the mind, while she is living on a houseboat, while she is homeless, while she is scrambling around trying to get a council flat, while she's got children, while she has a husband out of work, while she has a teaching job. And that is amazing persistence.

Now persistence might suggest she kept trying really hard. I don't know whether it's that or whether she's an obsessive, and she couldn't live any other way. I don't think it matters very much. It'll change for people.

Same with Katharine Graham. Even at her lowest point, she's obsessed with the news. She's a real news hound, you know, the newspaper is in her blood. Oh, my goodness, this woman is constantly sniffing out newspaper ink, right? But I think that's really important.

We rate that persistence or obsessiveness very highly in young talent, as we should. But we forget that it is still an important indicator about someone later in life. Maybe it's a more important indicator, because the fact that it hasn't worn off is actually quite telling.

This is a bit speculative, but I think these late bloomers take things a bit more seriously than other people. Not to the point of being humorless, but to the point where they may come across as a bit humorous, because oftentimes by middle age people are a bit like, “things are what they are. I am where I am.” Ray Kroc, who turned McDonald's into a global business, always had business ideas. It got to the point where his friends would joke that “Oh, Ray's had another idea.” But he was simply more earnest than the rest of his peer group. And again, I think that's very significant. Persistence and earnestness.

And then quiet. It's like what I said about Margaret Thatcher. She's keeping her work to herself. She's doing it in the background. Ray Kroc, too. He's quietly persisting. He's quietly getting on with it.

You can work in public. I don't think that's a bad thing, but I saw most of these late bloomers quietly working in private.

Now, some people have said my book is about hardworking people and that’s it. Maybe that's a legitimate criticism. And there are other sorts of late bloomers. But these were the things that stood out to me. As far as I'm aware, we haven't got another book that really goes into this topic in appropriate depth. Those were the main characteristics as I viewed them. But I'm very open to people coming along and saying they’ve looked at it in a different way too.

When I was reading your book, a word kept coming to mind: obsessed. These late bloomers were following their interests, and if something came of it, great. But if nothing ever came of it, they were alright following their obsession. That was what lit them up, made them feel alive, or what they couldn't get out of their heads and their hearts in some sense.

I would caution about that a little bit. In a sense, you're absolutely right. They were doing what they wanted to do. But I think they did feel the want of success. Very often, I think obsession and ambition are twins.

I believe the psychologist Frederick Herzberg came up with the theory that your internal motivation means you’re happy doing your work, even while you are very unhappy about the conditions in which you are doing it. That dynamic was often true for these people before they found success.

I think the other word that comes to mind is prepared. You note Margaret Thatcher: “chance favors the prepared mind.” You and I corresponded to set up this interview. I mentioned General Fox Conner, who I wrote a short biography about. He was a huge mentor of Dwight Eisenhower, who you also call out in your book. Before World War I, Conner remained a Major in the Army for 15 years. That whole time he was preparing; he was attending the right Army schools. He was becoming an expert in this, becoming an expert in that. He didn't know whether a war would come, whether his chance would ever come. But he acted as if it would. He prepared. That leads me to a question: how do we know we're preparing and not simply following our crazy interests or our obsessions? Or we're not just treading water in a stale pond?

A lot of the time you might not know. Maybe I'm too cynical. There's lots to say about Eisenhower on this. I actually cut a whole chapter about him, but I'm probably going to put it on my blog, because it's fascinating. He wrote to his son, saying. “Oh, it's a shame I'm going to retire before the war, but it's been a good life.” I find that amazing.

I wrote an article recently where I noted a famous quotation from F. Scott Fitzgerald: “There are no second acts in American lives.” That’s from The Last Tycoon, which was published in the same year that World War II came to America. And Eisenhower began his second act, which must be one of the great second acts in American history.

He actually thought, “Yeah, okay, well, I missed that. They're going to retire me and I missed out on the next war.” But he was fine with it because, as you say, he wanted to be in the Army. All his friends left the Army to make money, but he wasn't interested. That's important. But, again, it's notable that he's a man in the mid-century. It's easier for him to be happy with a choice like that. And with Eisenhower it was much more obvious. Everyone believed that there would be another war. When he was thinking, “Should I leave the army?”, his wife was saying to him, “Don't be crazy. There's no way you would ever be happy outside of the Army.” And his senior officers were saying to him, “There's going to be another war. It's just a question of when.” They thought his chance would come – it seemed quite predictable to them in between the two World Wars. Whereas for a lot of people, it may not be so predictable.

So no, you don't really know. Let's say you want to be something artistic, or something entrepreneurial – there's a lot more you can do. You don't have to wait, right? You can do a lot more and get your work out there. That obviously does not guarantee success. I think it'll vary a lot.

I almost wonder if you shouldn't worry too much about that. If you've made the wrong choice about what path you're on, how easy is it for you to change, anyway? I don't know. That's a very deep and difficult question. And I would think that talented people are good at intuitive imagination. They're good at thinking about whether they’re on the right path.

Something you just said sparked another question. You mentioned “you can get your work out there.” Late bloomers, like Penelope Fitzgerald – she’s writing and doing her work. You also mention the Paul Graham quote of expanding their chance of a lucky strike hitting them. Make your target for luck big. On the one hand you write, “If you decline to participate, the world will decline to pay attention to you.” The other hand, there's a limit to the groups, the networking, the selling yourself. In the modern world, that means social media, meetups, networking, all that stuff. And I really like this quote from psychologist Richard Wiseman, that you put in the book: “the lucky are relaxed, not anxious. They don't spend their life searching for their magic moment.” Can you talk about this dynamic of working the work, but also expanding your chance of getting the lucky strike? And yet, not being anxious about it?

There's a great difference between networking and self-promoting as a means to an end, and doing those things for their own sake. The more you can reach a kind of overlap between the work being self-promotion, presumably the less anxious you will be. While I'm not an expert on this, I do think a lot of people who are anxious are too focused on the foam on the wave of networking and self-promotion – as opposed to doing work and putting it out there.

Obviously, it's good to push your work, particularly for writers. You see a lot of people saying how it's difficult and demoralizing to have to do so much self-promotion these days. But it depends what you're benchmarking yourself against. If there's a particular type of success you want, and you're not getting it, you probably will be anxious about networking and self-promotion. This will cause you to do it for its own sake, and I think that makes it much less effective.

There's an interesting story in the book about Maya Angelou. She's done writing programs. She’s been around writers. She's written stuff. She's sent her work to writers and so forth. It's not going very well. She's in New York and not very happy. Her friend James Baldwin tells her to come out to a dinner party. She doesn't want to go. She’s demoralized by a lack of success. And he tells her “to just shut up and come to the dinner party. Let's just go.” So, she goes and there are publishers there. She's chatting, and she’s telling the story of her life, basically. These publishers, not being idiots, tell her immediately they will buy her memoir. Of course, it became I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

That’s not anxious networking and self-promotion. She didn’t moan, “Oh, God, I've got to go out and do it.” No – she has done loads of work and is ready to tell this story. I think this illustrates the difference rather well.

Obviously, people will counter this point by arguing that not everyone gets to go to those dinner parties. But that's a slightly separate thing. Getting the lucky strike, it does involve a lot of work.

The Wiseman quote. I mean, is the lack of anxiety genetic? Is it inherent temperament? Who knows? I would say, maybe don't worry about these things too much. But it's an interesting point.

You can work on your work. And when potentially interesting opportunities come your way, you can consider them. But you can’t determine who you meet. You can’t absolutely determine the circles you run in.

I know of really good work that is overlooked right now. I try to write about it on my blog. It’s a small example, because my blog is not that big. But I know it makes a difference to those writers whose work is getting overlooked.

So, there are two responses to “my work is getting overlooked.” I like the Samuel Johnson quote from the book: “Many have complained of neglect who have never tried to attract the world's regard.” You have to keep going. I'm not saying that it's going to work. I'm not going to promote some theory that this is the secret to success. But is there another method? I don't know. I don't think so. What's the alternative here?

I don't know what it is. It seems like a lot of people quit.

Yeah. And maybe that's the right choice for them, right? But it's an important point. Thomas Edison said, “People don't know how close they were to success before they quit.” Again, that obviously is not going to be true of everyone. But when we're looking at late bloomers, I do think it's significant. They kept going.

By and large, you look at superlative performers that the world knows, or a significant niche knows about. A late bloomer in a local setting could have a terrific inflection point and a massive impact in a“smaller way,” but it still matters enormously in their corner of the world. That's a really cool message of your book. It's not that you become Katharine Graham or Samuel Johnson. It's that in your corner of the world, you can have a different impact tomorrow than you had today.

I was careful in the opening of the book to say: we learn from the best. That's why these people are here. We're interested in great talent. It matters very, very much that we find and put to use the great talents. But this is a more applicable idea. I am interested more generally in the phenomenon of late bloomers.

A lot of people confuse the idea of success with doing what they want to do. People write to me, and they've done great work, and it is pretty much overlooked. Even though it would never make them globally famous, this book should change the way you think about things. Maybe you're just trying to do your thing, you're never going to be on the news about it, and that's cool.

This is amazing. I want to explore your idea of the “switch,” or as you put it, “an important type of late bloomer is someone who successfully changes the balance of their life.” Tell us more.

So, I think these are two slightly different points. Changing the balance of your life is like what I was just saying. You don't have to be Samuel Johnson, Ray Kroc, Margaret Thatcher, or Vera Wang to be a late bloomer. You can simply live differently. I think a lot of people do want to live differently in some way, and they don't quite know how to do it, or they're not quite sure if they want to make the series of tradeoffs involved.

The point about making the switch: I read this wonderful paper out of Northwestern. The question was, why do people have a hot streak? Artists, scientists, sportspeople. Why do they suddenly get this 10 or 15 year period where everything they touch is on fire, right? Everything turns to gold? The paper argued: it's an explore-exploit dynamic. So, people have a period in their career where they're looking around, trying new things, new ideas, exploring different options. Then at some point they go into the exploit phase. They say, “I've discovered the most interesting things from my explorations. I'm really going to work on them and deliver stuff based on them.” For example, if you're a scientist, maybe you've worked in an academic setting or a research lab. You've been exploring there. When you go into exploiting, you're probably going to a more commercial organization. Maybe now you'll have a team and you'll be a project manager. So these hot performers are really set up to exploit.

The Northwestern paper said these hot people have both phases. But what's really important is that they choose to switch. The particular factor that makes the difference for a hot streak is deciding to move from explore to exploit. That's really important. My argument is it happens to different degrees of intentionality with late bloomers. And it happens through networks, circumstances, all that kind of midlife crisis type things.

My favorite example is Audrey Sutherland. She looked in the mirror at age 61 and said, “Come on, lady, you're getting old. If you want to do this, you've got to go now.” And she did. She quit her job, and she went solo kayaking in Alaska in the Arctic Circle. She had bear encounters, and it was phenomenal. She kept doing it for 20 years. The woman is a total hero. Everyone should read her books Paddling My Own Canoe and Paddling North. They're very well written. And she was her own interruption. She knew that she had to make that switch. She knew that no one was going to make her.

So sometimes the switch happens in a very intentional way. Other times it's like Maya Angelou: James Baldwin takes you to dinner and you have an opportunity. You choose to switch into the exploit mode here.

Interesting. I love that explanation, Henry. You also write about late bloomers finding a peer group. You quote Paul Graham, “Nothing is more powerful than a community of talented people working on related problems.” You give the example of the Inklings of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and friends, and also The Club of Samuel Johnson, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Adam Smith, Edmund Burke and others. I found that so intriguing. How do people go about finding a peer set that they fit in with, that will support them, and that they can support.

Very difficult question. I don't know. Do they find their peer group or does their peer group find them? I don't know. That's a great question. I don't know.

I think this is linked to the idea that if you decline to participate, the world will decline to pay attention. While you're doing your work and networking, you're trying to find your peer group. Some late bloomers don't realize they should do that.

Not all of them have an important peer group, right? This is just one way it happens. There's a quote from Henry James, talking about Nathaniel Hawthorne. He says something like, “Hawthorne's obviously brilliant. He taught himself to be a genius writer. But it's such a shame he didn't have a group of peers to work with, because he would have learned it all so much quicker.”

It is not necessarily the only way. But once people find that group, it becomes very important. I mean, obviously, just you have to be looking. But it's very difficult to know. What group will be right for each person, because it'll change so much?

Where are the people who you find interesting? Go to them. Email them, find them on social media. There are lots of these options now.

It does seem to be the case a lot of the time. Doing the work is one thing. Associating with people – it's not just for promotional reasons. It makes your ideas better. It changes how you work. There’s a wonderful Ralph Waldo Emerson quote: “Truly speaking, it is not instruction, but provocation, that I can receive from another soul.” I love that. And I think that's true.

That's a great quote. As a Kentuckian, probably our most famous writer right now is Wendell Berry. He is an environmental writer. Very famously, he knew he was onto something in his writing career. He moved to New York to be in that milieu. And he rejected it. He said, this is not home. This is not where I need to be. The things I'm writing about require me to go home to the family farm in Henry County, Kentucky. He left New York and moved back to Kentucky. He did have support: Wallace Stegner and others. It’s so interesting to me that some people find their peer group is a place, an environment. They feel the need to go to a particular place and be surrounded by that place. They have to live a particular way in order to flourish. That came to mind as you were talking.

The two are connected, right? Whenever you read a Paul Graham quote, he's talking about startups. If you want to be Wendell Berry, walking around in the woods is probably a much better idea than hanging out in New York. If you want to do a startup, succeed in business somehow. For that person, walking in the woods is for weekends.

This is what I mean. It varies a lot. Depending on what you want to do and by temperament, some artists will flourish in a group. Other artists will do it on their own and it will happen in its own way.

There's a kind of wisdom in knowing which one you are. What is the correct balance for you?

One of the reasons I love this book is you wrote so many biographies of fascinating people. Even the little sketches of two or three sentences are fascinating. One person you wrote extensively about is Samuel Johnson. You and I corresponded about him as we set up this call. Until then, I'd almost forgotten I took a class in Samuel Johnson. I loved it. I have a bunch of his essays and books and James Boswell’s famous biography. Now I want to revisit all of that. I’d forgotten how wonderful a writer and moralist and philosopher he was. I would love to hear you riff on Samuel Johnson, his life, and why you love him so much.

Well, that's a very Johnsonian experience, because, of course, Samuel Johnson famously said, “Men more frequently require to be reminded than informed.”

I have a great love of Samuel Johnson, and have since I was 18 – well no, earlier than that. But when I was 18 or 19, I sat down to read him properly in university. He's one of those writers that some people just aren't going to love and some people are.

I have a great love of Samuel Johnson because of several things. First, he has this huge appetite for knowledge. We have a very myopic sense of the literary, a very narrow sense of what literature is. But of course, literature is a very, very broad thing. And if you look at the great traditions of novel and poetry and drama writing – it's about everything. Everything. In John Milton and in the romantic poets, you have many references to the most up-to-date scientific discoveries and ideas. Many of the newest political ideas, the newest philosophies – they're all being written about in poetry. Poetry is a real vehicle for ideas.

Johnson is one of the broadest of writers – economics, science, morals, philosophy, the nature of language. Johnson could write anything. We think of him as writing these great essays, the Dictionary, the essays. He also wrote books, advertisements, sermons, and legal opinions. Oh, my goodness, anything you can think of. In some ways, that's the mark of a true writer.

He's also personally a very fascinating individual. Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson is one of the greatest books. Johnson is alive and rambunctious on every page. He's argumentative, provocative, usually knowledgeable and entertaining. He's a candle that never goes out.

At the time, people complained about the same things they complain about now. People would read the Rambler essays and complain about the hard words in it. So it’s maybe an acquired taste. I don't know. But Shakespeare is the most important imaginative writer in English, and Johnson is the most important nonfiction writer. I see them as kind of twin pillars of English literature.

If you're going to make a tripod, I think you'd add the King James Bible.

Well, maybe John Wickliffe. But yeah.

Can you tell us a little bit more about someone who you uncovered as part of your research that you didn't get to include in the book, or only very briefly.

Yes, the Ray Kroc chapter was initially a double story. In that chapter I take David Galenson’s theory of late blooming in artists and I apply it to the life of Ray Kroc, who worked in fast food. I'm trying to show that this is a pattern that's not only for writers and painters. It also applies to people who fry burgers.

It was initially a double chapter on Ray Kroc and David Ogilvy. In advertising, words like tycoon, kingpin and mogul don't seem appropriate. Whatever you call him, he was the big guy on Madison Avenue. I cut the whole part about Ogilvy.

He has this fascinating life. He worked as a chef in a French hotel. He sold AGA Cooking Stoves. He'd worked in market research with George Gallup. He worked in advertising for a couple of years, but in the business side of it, not the creative side. He'd never written an advert before he started his agency. He worked in intelligence during World War II. The year before he opened his agency – when he was 38 or 39 – he was living on an Amish farm and he was play-acting being an Amish farmer. I don't think he was a very good farmer. So he’s kind of just a guy setting up an advertising agency.

But he'd been obsessed with advertising for his whole life. From his time with Gallup, he had this idea of bringing market research into advertising. At night on the farm, he would study the history of advertising. By the time he opened his agency, he really knew everything there was to know about advertising. He demonstrated that kind of quiet persistence. I took him out of the book. Maybe I'll publish that chapter on my blog, because he's a very interesting figure.

That's great. I would love to read the chapter about Ogilvy. As we age and if we haven't caught the success we think we are capable of, what are we hampered more by? Are we hampered more by our diminished sense of ourselves through frustration and failure? Or are we more hampered by other people's disappointment in our lack of success?

I think that will change a lot depending on the individual. I think that's a question of personality and temperament.

Maybe some people don't feel that disappointment at all.

I don't think that's a thing we should generalize about. It's a great question, and I think people should give it some attention. But I don't know that I've got a good answer. Thinking about the people in the book, we’d have different answers for all of them.

Katharine Graham very clearly felt a low sense of herself because of the treatment from her mother and from her husband.

Well, but it's both, isn't it?

And it's both. Yeah.

By the end, she clearly felt poorly inside and from people’s treatment of her. That's my point. I think the answer is often quite complicated.

If you're someone reading this interview, or reading the book, and you feel deep inside that you have some contribution to make to the world, but you haven't yet: How would you say that you can improve the odds of making that impact?

Well, I don't know, because again it would vary so much by the person. Some of the main messages of the book come through: do the work right, and then get it out.

Yes.

Think about: where is the gap in your opportunity? Are you in the right circumstances? Changing the culture that you're operating in and living in is very significant. Do you have the right peer group? All these things we've been discussing.

Do you need to look at yourself in the mirror, like Audrey Sutherland, and say, “Come on, if not now, when?” I think all of these things are there. The particular combination is down to the individual.

A lot of books would tell you what the answer is. But I think that's a lie. What I'm trying to do in this book is give you all these different bits, and then your answer will be some version of it for you.

Yes, right.

But I can’t tell you the answer. You are not an average line on the graph. You are who you are.

Like I said at the beginning, Henry, I love, love, love your book. You’ve made such a valuable contribution to our appreciation of an underutilized source of talent – late bloomers. I'm curious. Coming out of publishing the book, what are the next set of questions related to late bloomers that fascinate you?

I don't know if I have any more questions about late bloomers now. I'm interested to note that there are so many of them in public life.

There's a wonderful article, I think, in the New York Times, that shows many charts of when Taylor Swift's most successful songs and albums were launched. To me, she very clearly seems to be a late bloomer. I was fascinated by that.

The debate, if that's the right word that you're having in America about Joe Biden's age, it’s remarkable that you have a President doing the job at that age. It's symptomatic of what's happening in the wider workforce. There are many, many more people in work above retirement age than there used to be, both in America and here in Britain. There's a big trend there.

We've also got older actresses winning Oscars; Larry David is doing the final season of Curb Your Enthusiasm in his seventies. There are a lot of late bloomers in the culture.

There was a big video shared somewhere of a woman who became a park ranger in her 80s and now she’s 100 years old. These late bloomers seem to be a real phenomenon more and more in the news.

Let me ask you a couple of questions about your work and you. What were the big takeaways you took from writing the book? It could be lessons from the book, or just the process of writing the book, or the research, or working with Tyler. What do you take away from the last year or year and a half of your life?

A lot of things. Oh, my goodness! In the book, there are a lot of topics that I either hadn't considered properly, or I changed my mind about. I was most fascinated by network theory. I came to take that idea much more seriously than I had – the importance of peer groups and networks.

I'm very pleased to be part of the Emergent Ventures group, which is where I got my grant to write the book. The people in that group – endlessly interesting. I came to both a theoretical and a practical appreciation of networks and peer groups in a way that I had not. That's the biggest thing for me.

Interesting! How has writing the book changed your work, or your life, or your approach to life?

Well, I quit my job. So that was quite a big change. And my wife chose not to work when we had children, and she's homeschooling. So that has also been quite a big change.

In many ways you would look at it and say, “This is not a sensible arrangement financially and professionally.” I’m trying very hard to make a go of doing exactly what I want to do.

And Seinfeld! Jerry Seinfeld gave an interview recently. When he got the opportunity to do the pilot for Seinfeld, someone who was then a very significant comedian, said to him, “Don't let them change it. All the suits are going to tell you you've got to do it this way, you’ve got to do it that way.” He said, “Do it exactly how you want, and then when you fail, you won't care because you'll have failed, but you'd have done your thing. Whereas if you fail, because you took all this advice and did what they made you, you’ll resent it.” That's a really good. I like that, and that's kind of where I am.

What's the next work you want to do?

I've been thinking a lot about patronage and the question of patronage. Writers used to have patrons who gave them money, right? We think of it in politics – politicians give their associates jobs and so forth. In some ways, this is a bad thing. It's favoritism. It's nepotism. Economists would say it's not very efficient. If you allocate positions based on who you know rather than based on meritocracy, you're obviously going to get inferior performance.

And yet, if you look around, there is a lot of patronage in the world. Through grants and schemes like them. But also, in a corporate environment, you have to have a mentor to rise above a certain level. Now that's not exactly patronage. But you want your mentor to become your patron, and say to the other bigwigs, “This person is great and we should be encouraging and promoting them.”

Why does a profit-driven corporate environment use the supposedly inefficient mechanism of patronage? This is a question that I'm working on right now.

I also have written a series of articles about talent for a firm called Entrepreneur First. I wrote a piece about Rene Girard and his theory of mimesis, which a lot of people think explains the world. I really enjoyed writing those pieces as well.

Would your ideas around patronage extend to sports too? It seems like so many sons and daughters of sports figures are becoming well-known and successful athletes themselves. They've lived that life since they were two years old.

Yeah, that's interesting. I haven't seen any studies about patronage in sports, but I'm gonna go and look that up. But I've been reading the studies and trying to work it out. Because patronage obviously works in some way. It's honestly not totally rigged. I'm not a very sports-oriented person, but that's a great hint. I'm gonna go and look that up.

But I'm actually more interested in this question of patronage as a selection mechanism. Why is patronage being used in highly meritocratic environments, when the economic research suggests that it should be counterproductive?

I wonder how that relates to Boards of Directors, too. Going back to some of my early work, typically the CEO selects or has a heavy influence on new board members. There's something like patronage there. Does that lead to better outcomes?

This is my point, right? It's a question of talent selection. Patronage is still a very live issue in modern society, and I think it should get some more attention.

Well, I can't wait to read whatever comes out of your research and analysis of the topic.

Great.

Henry, this has been amazing! I’ve loved this conversation. I'm so grateful for your willingness to speak with me and all your time. This has been a highlight of the year!

Well, you had really good questions and you made me think. And now I'm worried that I'm going to have to change some bits of the book. Haha! So that was a good interview for you. Haha!

(Amazon Affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)

Thank you so much for this interview. At 53, I think a lot about what I want from a second act. As a person living with Turner syndrome, I think a lot about the precious gift having a first or second act is at all. Having just read your essay about the 10th anniversary of your heart surgery, I know you get what I mean. (Not sure why I felt called to leave a comment here and not there.) Thank you for the gift of your writing. Thank you for the gentle reminders to pay attention. Sending you thoughts of health and joy and love this day.

how delightful, thank you so much!