When You Eat a Mummy, You Desecrate a Land and Destroy a Soul

A conversation with Egyptian-American poet Sherry Shenoda

I could describe Sherry Shenoda in many ways: poet, pediatrician, immigrant, intellectual, mystic, mother, daughter, granddaughter, aunt, wife, Egyptian, American, Coptic Christian, muse and hearer of the muse. Yet she defies description. In a world of people clawing desperately to stand out, I find her remarkable for her desire and willingness to stand in the long flowing river of beautiful traditions, including of family and faith.

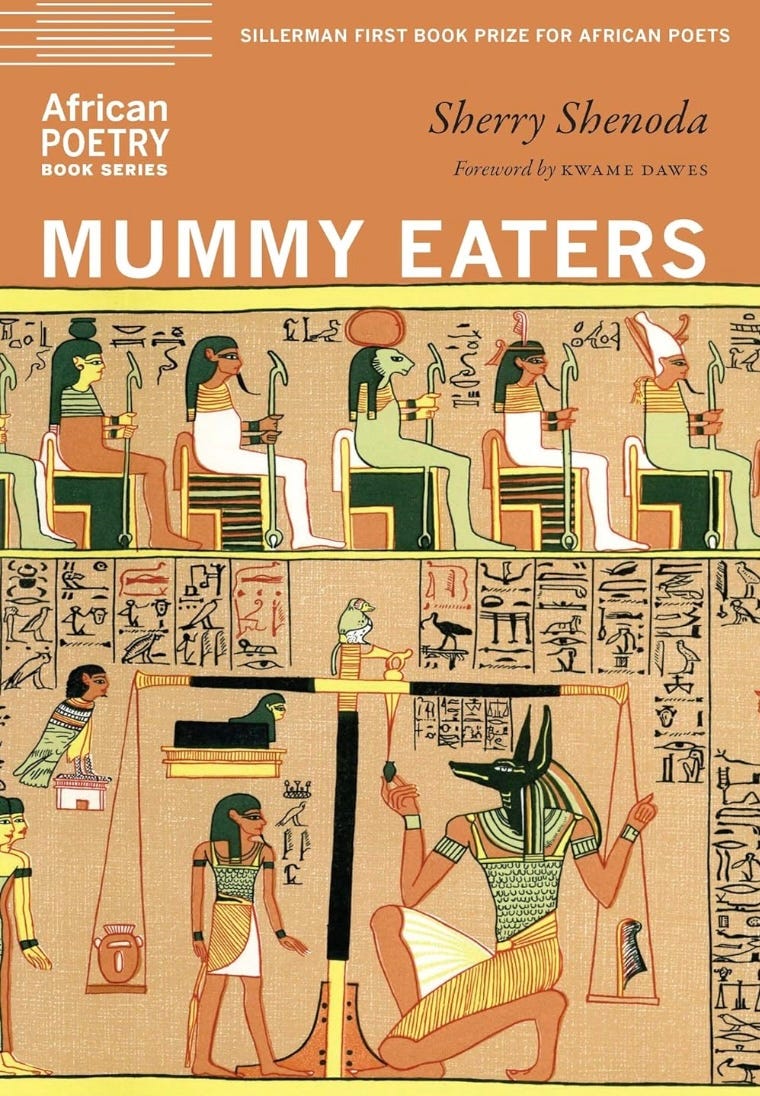

Sherry and I talked two years ago, about her first novel, The Lightkeeper. Sherry kindly agreed to talk again, this time about her book of poetry, Mummy Eaters. The book was longlisted for the National Book Award in Poetry in 2022, and won the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets.

Beyond the awards, I found Mummy Eaters a hard, visceral mix of intellect and emotion, of ancient longing and complex relationality. In it, the poems engage in a dialogue “between an imagined ancestor, one of the daughters of the house of Akhenaten, and the author as descendant.” It creates a captivating construct for Sherry’s ruminations on identity and ownership, desecration and courtesy, and place and spirit. All through it, I found a wise soul seeking, if not answers, then a credible way forward.

And much of that path involves breathing to life more poetry in the world.

Thank you, Sherry, for a sublime exchange.

I read this book and I thought, “Wow, this is different from your first book, The Lightkeeper.”

Very different, yes.

But I love that. I've said this to a couple people now, but I'm tired of reading Cal Newport's books. I love his ideas, I love his podcast. But every book is between 220 and 240 pages, he stamps it out, and then two years later, he writes another book of 220 to 240 pages. It's the same formula. I'm bored with it. Some topics deserve 500 pages, some deserve four pages. Go with what the topic deserves.

Yeah. But I'm glad it was a good read for you. I'm glad it spoke to you.

Absolutely. To start, why did you write Mummy Eaters, and who'd you write it for?

I was trying to understand my Coptic heritage, and I wanted to get at the link between Coptic Christians and their ancient Egyptian roots. So, I wanted to understand the context historically, as well as in the light of colonialism. And I wanted to move closer to my grandmothers, neither of whom learned to read, and my great aunt. She did learn how to read, but my two grandmothers didn't. They're all gone now. The ultimate answer to your question, the target audience is probably me. Which I think is probably the target audience for most writers. I write to figure out what I'm thinking, as I'm sure you do. And I'm always endlessly grateful if any of it translates to other people's life experiences.

You explained it a little bit in the beginning of the book, but why did you title it, Mummy Eaters?

Okay, so this refers to a practice, a gruesome practice in the 16th and 17th centuries, when Europeans would eat Egyptian human remains – mummies – for medicinal purposes. There is this conception that Europeans were civilized in a way that the rest of the world wasn't. I just wanted to highlight the maybe uncivil and barbaric ways that native Egyptians – alive and dead – were treated. It's a study on civility. The mummification process that the ancient Egyptians used was very reverent. It was thoughtful, it was deliberate, it was formulaic. But the way that the remains were dug up and used wasn't. And I wanted to lightly sketch this question that perhaps incivility existed because they weren't seen as being human, which I think we're gonna get to later. That was the reason for the title.

You mentioned the mummification process being ritualized. The word that came to mind is “sacred.” Recently, I took a class on the Tale of Sinuhe from 1900 BC or so. Sinuhe leaves Egypt under strange circumstances, but he's very keen to return for the end of his life, and for his mummification and burial. In fact, the Tale is told from the perspective of him already being dead. He's telling the Tale after his death. Sinuhe is a very interesting character – I'm not necessarily sure that what you see is what you get in everything he writes. But to me, it's very clear that he sincerely wants to return to Egypt. The place of Egypt and burial in Egypt is critical for him. I'm interested in your view. In Mummy Eaters, the land of Egypt is hugely important. The mummification process is hugely important. You write about Egypt as sacred soil, about its desecration away from that sacredness. I’d like to hear from you about the importance of Egypt as a place, as a sacred place, for humanity, but also for you.

Egypt is the land of my ancestors. And I was born in Cairo. I've been back multiple times since immigrating to the United States, but it doesn't belong to me in the same way that it would potentially belong to my cousins, who still live there. In some sense, the immigrant experience is very different from living in a place. But it still feels like the place that I came from. There's this curiosity that's born of distance and a desire to understand where my people came from, the land that nurtured my ancestors. In some broader sense, I think ancient Egypt belongs to the world, to humanity. So Mummy Eaters has been my way of starting to understand this incubator of culture, spirituality, human intelligence that was ancient Egypt and carried forth into modern times.

Let me return to your purpose and process in writing the book. How long did it take from your first idea of it to getting the manuscript done?

This was very different for me, Russell. This book took me by surprise. I normally write at a glacial pace, and this is not unrelated to the fact that I have three small boys. But this book was finished in about six months, which is lightning fast for me. This book wanted to be written. There was something urgent about this book. It goes back to what I was saying earlier that I wanted to understand. There was something that I wanted to untangle about where my family came from. It was a very urgent writing process. Very different from my novel, which took five years.

Pull on that thread a little bit more, Sherry. What were you trying to unravel or understand?

At its root, I wanted to get at the sins that we commit against each other. The ways that we commit violence against each other. As somebody who's slightly removed from that violence, what it means to forgive, because nothing was done to me directly, right? I didn't have my tongue cut out for speaking Coptic. My remains were not exhumed and consumed. I did not directly experience colonization or theft, but some of this was me trying to grapple with the question of, what is the statute of limitations on something that happened to your ancestors in the past? How long does generational trauma continue? And is it okay to even call it “generational trauma”?

At the same time, I wanted to work on this parallel storyline. In the beginning of the book, this ancestor of the writer, one of the descendants of this pharaoh, Akhenaten, is being mummified. It also follows her journey into the afterlife. We dug people up, but they were actually people. And we consumed them. What did it mean spiritually for them to bury their human dead, and to preserve them? Why did it matter to have the body in the afterlife? Why did the incarnate, the human person, matter? Why did the physical body matter?

In modern times, we sometimes incinerate our dead. We don't have the same reverence for the body of the dead that they did. I wanted to understand some of that as well. And I think in the seed of understanding their reverence for the dead, is the answer to why resurrection was so important to them. Because the body itself was really important. In the incarnation is the seed of what eventually becomes resurrection for them – the afterlife. That is their version of what we would think of as heaven.

In ancient Egypt, the pharaohs were seen as an incarnation of the gods. The royalty was the incarnate god. They very much saw the things of the world and the key people of the world as the incarnate gods. Is that what you're speaking to in terms of the incarnation of the holy, the sacred, and the resurrection that everyone's bodies play a role in the sacred cycle? And mummification was a very important part of that? It was carrying forth and completing the cycle.

Yes, well said. And you can see that in the story of Osiris. It's very cyclic. His body needed to be recovered to be resurrected – essentially, to be brought back. They were very, very reverent about the human body.

They were reverent about the human body. They were also reverent about the place, the land. The name of Egypt is holy. The love of Egypt, the land, the place, is evident in Mummy Eaters. You and I have talked about Wendell Berry before - his view that people should have reverence for a place. Talk to me about that – not only the holiness and the sacredness of the human body as related to the divine, but also of Egypt as sacred and holy, and in some sense, distinct from other places. You were born there, but you haven't lived there for long. Yet you still feel a powerful connection with it. And I know your family does too. Talk to me about the specialness, the holiness, the sacredness of this place, Egypt.

Is it sacred compared to anywhere else? All the land is sacred. The very first poem of the book is called “Sunflowers of Fukushima.” It's an invocation. There's this back and forth between speaking and silencing throughout the book. In Japan, from my understanding, nothing could grow in the land that was affected by the nuclear fallout. A monk – Monk Koyn Abe – planted a field of sunflower seeds, which basically pulled up the radiation, the toxicity that was in the soil. That was my prayer for the book – to pull up some of the toxicity that had been sown throughout time, whether it was through colonization, desecration of human remains, or the frequent conquest of Egypt. Egypt's been conquered so many times, Russell. So many different times in different ways.

I wanted to pull up the toxicity from my own experience of it, and also from my own generation's experience of it too. We have to process grief in order to grow from it.

All land is sacred. I don't know that Egypt is more sacred than any other place. But some of the sacredness of the land is the way that we treat it. Because Egypt has been defiled so many times, this was my way of processing, and pulling up some of the toxicity that I have come to associate it with the land. Egypt is a very fertile country. The Nile River valley is some of the most fertile land in Africa. In modern times, the Egyptian government would let people build on what used to be farm land. Then they realized it was the place where the Nile flooded, which would bring this intensely rich soil up and allow growth in the middle of the desert. Now they don't do that. We have a dam and we also build on top of that land. They realized that you can't build on what is essentially farm ground.

The way that we treat the land has a lot to do with the sacredness of the land. If you build on farm land, if you don't allow the Nile to flood, if you have people living there, those decisions have consequences. Again, that goes back to the sacredness of the land – the way that we treat it, the way that we dump on it, the way we desecrate it.

You are getting at a theme of the book – love. A lot of the love in the book is love that's gone awry, or love of the wrong things. For instance, the mummy eaters of the 16th and 17th centuries, they loved health and life in a certain way, but in doing so, they also desecrated something. It's a love gone awry. Talk to me a little bit about that, about the theme of love in the book, about how love goes awry, when it's not directed at the right object.

In the Coptic Orthodox tradition, we believe that humans bear the image of God. And if God is love, a lack of love distorts the image, right? Across the spectrum, right? You have verbal internet abuse toward strangers on one end, all the way to genocide, on another end. I think we have to dehumanize people in order to do that violence to them. Love humanizes, a lack of love distorts the true image. Copts believe that God spoke the world into existence in love. So in this series of “Silence” poems, I explored the ways that we silence each other. At its root, when we silence, we deny the other people's humanity. That makes it really easy to commit violence against them, to erase them. Once we've removed their ability to speak, removed love from the equation, whatever nefarious thing that we're going to commit becomes much easier to do.

Let's talk about a love that you carve out as special in the book. You specially emphasize the love between a grandmother, daughter and granddaughter in the book, and as I read it, imbue that love with a special grace. It appears as an unbreakable, incorrigible, incorruptible love. Tell me, why do you single out this love between a grandmother, a mother, and a daughter?

Yeah, There is a sacredness in the love passed down from my grandmothers. This is just my experience, of course. It was broad, it was deep, and it felt unconditional. It didn't ask for anything. It was a very feeding and nurturing, love. A lot of the love that my grandmothers showed was through food, which is a lot of people's experience.

There's nothing you can do in the face of that love, other than to receive it. You just bear it somehow. It's like squinting into the sun.

The love between mothers and daughters is a little bit more complicated. I've been abundantly blessed by my mother, but the love passed down from my grandmothers is just different. My experience has been that it’s just a very different love. It doesn't ask anything.

There’s a lot of truth in the old saying: “the wonderful thing about being with a grandmother is simply being with a grandmother.”

Yes, that's true. Yeah, it's this sense of presence. They're with you in a way that's very different. They don't want anything from you.

Let’s discuss the themes of mummification, and the cycle of incarnation and renewal. You write a lot about the dead recognizing themselves so that they can attain the afterlife. You relate that to a sense of us modern humans not recognizing ourselves. There's something missing in our identity. There's something we are not recognizing in ourselves. What are you saying there? What's missing in how we identify ourselves today?

Mummification was about maintaining the physical integrity of the body so that the dead could recognize themselves in the afterlife. In a sense, they're buying some time to slow down decay long enough for the soul to recognize itself. In a similar sense, being truly alive is also about maintaining integrity – mental integrity, spiritual integrity. Being integral – that word means to me to be truly human, truly among the living. I found the physical integrity in mummification a really beautiful parallel for spiritual integrity.

Regarding the issue of integrity, there is a lot of scholarly speculation about this pharaoh, Akhenaten. He was called a heretic pharaoh for adopting a monotheistic worldview. Some say it was a political power move. Others said he was just plain mad. But I wanted to explore another possibility: maybe he truly believed it. Maybe he thought that there was a single God and he tried to have some integrity about it. Maybe that was the arc of his life.

Of course it's all speculation, but it was an interesting thought experiment for me. What would it look like if you were God on earth – as the pharaoh was – and you had integrity? They probably killed him. We don't know exactly what happened, but what does integrity look like for that ruler? Again the physical integrity of mummification in my mind was a parallel for asking, “what does spiritual integrity look like?” How do we recognize ourselves? How do we sleep at night? How do we live with ourselves?

Interesting. You're Coptic. This brings us very close to Christianity and the story of Jesus, who knew he was God and did something about it.

And was killed for it.

And was killed for it, yes. Interesting. As I read the book, I saw a lot about the religion of ancient Egypt and I saw a lot of parallels in my very shallow understanding of Coptic and Orthodox Christianity. One thing that I didn't notice a lot was Islam. There's one reference to it at the end of the book. Tell us more about that.

It was largely a function of the timeline as well. Coptic Egypt predates Islam, but you can’t have a real conversation about modern Egypt without addressing Coptic–Muslim relationships. My attempt at that was the poem, “How to Silence IV,” toward the end of the book. It's about the things that really matter between two groups of people that have to coexist, but have very different understandings of truth. These are conflicting ideas about what is true. What actually matters when you have that sort of tension? That poem was my way of trying to address that question.

It outlines a moment in time when my mom woke up after surgery. They thought she was going to die. She had a really bad abscess. She was unable to take care of her baby. She almost lost her life. My dad was across the ocean. My mother is a doctor and her Muslim sisters took her call shifts and divvied them up. One of them was sitting by her bedside, chanting from the Quran when she woke. I was hoping that image would convey my understanding of what's important between Copts and Muslims. It goes on a little bit longer, but I think that's the most important portion.

There's so much silencing in the book, dealing with silencing. And it ends with wondering – instead of giving air time to the haters, what if we could chant of God, in whatever tongue is left to us?

Another theme of the book is possession. Who owns what? Who owns the mummies? Who owns Egyptian heritage? You said earlier that in some sense, ancient Egypt belongs to humanity, to the world. You seem to have views on who owns Egyptian land, Egyptian language, the treasures of Egypt. Who does own them and who should own them? I'm coming with the easy questions, Sherry. Just one softball after the other!

So much has been stolen from Egypt, Russell. And from Ghana, from China, from Greece. The list is embarrassingly long, right? There's a British Museum Act that makes it functionally illegal to remove objects unless they're duplicated or damaged or no longer part of the public interest. But sometimes we complicate things. People talk about how displaying things in encyclopedic museums allows “the world” to access them. Not everyone has access though.

They say these objects were acquired legitimately. But it’s really simple: We shouldn't keep things that don't belong to us.

Whether we knew at the time that something was stolen or not, doesn't change the fact that it was stolen. That argument actually would never hold up in a U.S. court, right? “Sorry, officer or judge, I didn't know it was stolen.” No, it was stolen and you had it.

The fact remains that a lot of these items were stolen, whether through ignorance of the person who took them initially or not. But Egyptian artifacts aren't subtle, Russell. You don't look at them and wonder if they were Egyptian. Um, no – they had a brand. They're obviously Egyptian. Maybe the origin is not under question. I understand their arguments for keeping objects in other museums. I don't think all of the treasures of ancient Egypt belong in the Egyptian museum. I think it's fair to share some things. Maybe not an entire place, like the Temple of Dendur at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It's like they just picked it up and moved it.

There's a joke that the only reason that the pyramids are still in Egypt is because they were too heavy to move.

I understand: it's a complicated question. The more complicated question is: what do reparations look like? What does restoration look like? That is maybe above my pay grade, but I think when something is stolen, we should at least acknowledge it as being stolen.

I also think displaying human remains may not be necessary. People are interested in what mummies look like. I think it's okay to show images of that, but I don't know that the remains need to be in museums forever. I wonder if there would be a more reverent way to deal with human remains than the way we're doing it now.

Yes, these questions are complicated. But stolen is stolen in some sense.

I want to nerd out with you for a few questions. You've written a real intellectual tour de force. I circled 83 words or people or places that I didn’t know. And I love that. I love stretching and learning and being confronted with things that I don't know and therefore am not comfortable with. And this was a book very much in that vein for me. You confronted me with ideas and words and themes I had not encountered before. Did you simply know all these references off the top of your head? Or did you also have to research and study some things and think more about them and look for connections?

Thank you, Russell. I do a ton of research. The answer to your question is: No, I didn't know all those things. I do a lot of research. Like you, I love to read and I learn and force myself out of my comfort zones when I can. In writing this book, I went to a lot of primary sources.

I read a ton, but also there was a lot of oral history. I sat with my dad quite a bit. My dad is a wonderful oral historian. He's the keeper of a lot of the memories that are still available. There's so much that's lost even in a single generation. Many things my dad knows that I don't.

That's wonderful. I love many things about this book. It forced me to look up and learn so many things I didn't know before. And that brought into view many themes I hadn't really thought about before. That was wonderful.

May I go back, Russell, to something you had asked me earlier?

Of course.

You had asked about self-recognition. We had talked earlier about this series of “How to Silence” poems and that we have to dehumanize the other in order to be violent towards them. I wanted to add a bit to that.

There's a spectrum of silencing in the book. But I wanted to especially highlight the casual silencing, the thoughtless, the ways we don't intend to silence, but we simply didn't care enough to understand and harm is done that way. I'm a pediatrician. In pediatrics, the most common form of child abuse is neglect. It's not providing what's necessary. And mistranslation is the beginning, I think, of silencing in many ways. Denying people language, mispronouncing their names – it seems really innocuous, right? In the book, I am trying to give a glimpse of how catastrophic a mistranslation could be. So my Great Aunt Marie, for instance. It's mentioned very briefly, but she had a pacemaker placed in her chest without her consent. She speaks Arabic, but was sent a Spanish speaking interpreter.

Actually, the title of the book also points to the mistranslation of the word “mummy.” In the Persian, they referred to medicinal bitumen, which is a viscous material, a healing plant. And mumia – medicinal bitumen – was mistranslated. You could argue that mummy eating would never have occurred if not for that mistranslation. In the same vein, if we don't neglect one another with respect to the spoken word, we wouldn't end up with these figurative consumptions. So we figuratively consume each other, simply being neglectful.

Then there's the rest of the spectrum, – of deliberate kinds of silencing, like the obvious ones, like violence. But I wanted to just highlight the seemingly innocuous ways of silencing too.

Sometimes I wonder if the innocuous things come about not from bad faith or malfeasance, but simply a confrontation with another that you just don't know what to do with. There is that language barrier. There is the inability to actually communicate and you're left in a place where you have to act and you just don't know what to do. As a total armchair general, I’ve studied war for 25 years. I never understood why people actually went to war until I went to South Korea – and I didn't understand a single word. For some reason, being immersed in that environment, I appreciated misunderstanding in a way I hadn't before. Of course, that leads to a very slippery slope: it becomes very easy to dehumanize what you can't understand.

Yes. Sometimes, I think of a simple example. When someone is hurting, like after a death in the family, for instance, sometimes that person is suffering because they're lonely, but people just don't know what to say. It's a type of mistranslation, it's a miscommunication. Really, they want presence, they want someone to show up or be there physically. Maybe not even say anything at all. But there's almost a language barrier in a sense – and it can cause harm because that person is then isolated and is grieving alone. That’s an everyday example. Then of course there's the actual language barrier, like you were dealing with a totally different culture, in a place where you couldn't actually speak the language.

I also wonder if we're isolating ourselves more and more. I am not the first observer of this. I was traveling this week and I went to breakfast in the hotel restaurant. Every single person was on their phone. They're at a meal – by definition, a communal event. And they are disengaged. They are isolating themselves. They are not with or attempting to create community or even confrontation with the other. It was strange to be the solo person, and yet the least isolated person, in that environment.

We could talk for another hour about that. There's definitive data now that depression and anxiety worsen – especially in children – when we’re on phones and social media. I recently read The Anxious Generation. The charts in it are really damning. It's terrifying what's coming if we can't get a hold of this, because we already have an epidemic of loneliness. It's going to worsen.

The more we isolate ourselves, the less we can communicate with each other. We're coming up on an election. And some of the issues that we have are just massive miscommunications. We can't sit with somebody who doesn't believe the same thing we do. We think of differences in opinion as being violence. But they're not necessarily violence. They're differences in opinion that can be potentially sorted if we could sit down and communicate properly.

Communication is a bit of a lost art right now, and I think it has a lot to do with what you're saying. People are in their own little worlds. We don't look up from our screens, and we don't read. I feel like if we read more novels, maybe we would be in a better place, or talk to each other more.

Totally agree.

Before we started recording this interview, we were talking about A Month in the Country, which is a wonderful book. There's so much truth conveyed in, what, 140 pages? It's incredible. You can be a more tolerant person, potentially, after reading it.

I think you’re right. I'm reading James Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson, which I read 20 or more years ago. I interviewed a gentleman named Henry Oliver recently. He and I were nerding out on that book. I took a class on Samuel Johnson in college, and I’d forgotten how much I loved it. Anyway, what's striking me about the book right now is how wrong Samuel Johnson was about so many things. But I see him in a more human light than I did in my first reading 20 years ago. That's been a curious revelation for me 400 pages in, a little less than halfway through the book. He seems really wrong, but more human.

Yes. And you've experienced grief in those 20 years. You've experienced life and grief, and I feel like it makes us more able to bear other people's imperfections.

Suffering is learning. This is a point of the Eastern philosophies and religions, and of Sophocles and so many others. Suffering is learning.

Yes.

While we're on the subject of emotions, you've written an intellectual tour de force. This is also an emotional tour de force. Like you, Sherry, it is understated and polite and courteous, and you note that courtesy at the end of the book. Whatever has happened, we owe each other courtesy. But I found this very emotional nonetheless. This book has an edge that your first book, The Lightkeeper, doesn't have. It's very different. It shows disappointment and maybe even a touch of anger. In my margin notes in the book I wrote, “This exudes an ache, a hurt of generations, of centuries.” Talk to me about your emotions in writing this book.

Russell, I think writing anything that hurts, which is usually the stuff that matters, requires that we process it. This isn't to say that raw, unfiltered grief can't be written. It can – there's a way to do that.

But in order for it to not be like a diary entry, I think it has to be lived with and processed in some sense. This was my attempt to be as clear-eyed as I could. And some of the anger still seeps through. To be as clear-eyed as I could about colonization, its legacy, which in many ways is erasure.

One example off the top of my head: Copts at one point would have their tongues cut off for speaking Coptic. Those things might not have happened to me directly, but they did happen to my ancestors. And they do have repercussions today. The result now is that Coptic is a liturgical language. It's not spoken.

In one of the poems, I address this issue of seeing a hurt and naming it. There's power at least in naming the hurt so that we can acknowledge it, try to forgive and grow – and maybe grow past it, grow from it, and thrive. There's no point in talking about generational trauma if we don't talk about mitigation and thriving. Nobody wants to just exist here and wallow in the past. We all want to live a good, full, healthy life. Forgiveness is a really big part of that. Whether there's anything to forgive or not, whether people think I have anything to forgive, in some sense, these sins were committed against my ancestors. But I think that even their repercussions have to be forgiven.

The fact that we don't speak the language of my ancestors or any of the other things, the fact that I can't walk into the museum in Cairo and see something because it was stolen, these are things that we have to process. Naming them helps. Forgiveness helps. Then we can hopefully thrive in the aftermath because we've pulled up the toxicity from the soil.

Like you were talking about earlier at Fukushima.

Yeah.

I love that. This is a weighty book, a serious book. But I also have to tell you, in a few instances, I found it uproariously funny. You write this about mummification: “Like plastic / surgery but the highest stakes / nose job of all time.” I'm reading it while sitting in a pool chair and I crack up at that line. It was hilarious.

You're totally right. So, no, absolutely. Thank you for finding my humor funny. Humor is one of the ways that I process work. In some parts of it, it's sometimes easier to approach something really serious with humor. Not to lessen the gravity of the thing, but to make it processable, for lack of a better way of phrasing. I'm glad that parts of it made you laugh.

I thought it was hilarious. I thought it was brilliant. It was so funny. Let me ask you a couple last questions. You end the book with a poem titled “Letters for My Grandmothers.” You write about the special love between grandmothers and granddaughters. You give two different views of femininity in that poem. You talk about an ancient view, and you talk about a modern view.

The poem that you're talking about, “Letters to My Grandmothers,” starts with a giantess stirring onions into the 16,425th meal, which is about halfway through a life. But she knows no more of letters than the slanted slash of a signature. Both my grandmothers were illiterate in that sense. But neither of them was any less worthy than I of language, of learning the letters. In the Coptic tradition, when someone dies, we say, “May we live and remember.” At the beginning of the book, I put that in the Dedication to my grandmothers.

Being forgotten is another death, is another form of death. And I wanted their memory to carry on. Mummification, as we were saying earlier, is about buying the dead a little bit more time to recognize themselves in the afterlife. This book is dedicated to my grandmothers for their really unflinching love, to perhaps buy them a little bit more time in remembrance.

I love that. Well, let me end with this question, Sherry: What's next? What are you working on now?

I'm about 70% through writing a novel. When I talk about it out loud, the target audience is really me. It's about a perfumer in the 1920s in Paris. He loses his sense of smell, and with it, his memories, because his memories are so tied up in his sense of who he is.

It's about his journey back to himself through scent. I've been thinking a lot about memory and scent. Actually, I see the pile of books that I've been researching on perfume sitting at the top of my desk. That's just the perfumery section. We were talking earlier about research.

That's what I'm working on right now. And it's been a wild ride. But it's been fun.

I think that's brilliant. I can't wait to read that!

Thank you.

Smell is the sense that is least well-written- and -thought-about. Over the years, I've read a lot about World War I. The thing that I can't appreciate or understand or comprehend is the smell of those trenches.

It’s so interesting that you say that. Because this man, this perfumer, lives through World War I. There's a whole section where he's remembering the scent of war. There's a perfume forum called Fragrantica. There's one author on it who does an entire post just on the scents of World War I.

Wow.

It was such an interesting read.

Yeah. The scent of war and death and burning and rotting in the sun.

It was also in some of the primary sources that this post writer looked into. It was also the scent of stuff that's wet and it didn't dry properly. Things like sandbags – they didn't dry properly. Dead animals, horses in particular. And then there were the biological weapons, some used for the first time, things that smelled, like bleach.

The character in my novel has a flashback in the story. His wife is cleaning something. And he has an intense reaction. He lives through World War I and he’s processing that because the trauma remains. I think even if you don't have the exact memories, I think sometimes trauma is just written in the body in a way that is still there. It'll be interesting to get your feedback about it since you're interested in World War I.

Can I take that statement as an indication you might be willing to join me for a third interview after this novel comes out?

I would love to. That would be so much fun.

That'd be awesome.

Thank you so much, Russell. You are so kind and generous in your engagement. Honestly, it's such a delight to speak with you. It's like every author's dream that someone engages on this level with a work. It's so special and so generous. Thank you.

Thank you. I love your writing. And I love our conversations. I learned so much. You give me so much to reflect on and to ponder. And it's always wonderful to see you and to get a chance to talk, Sherry.

Thank you so much, Russell. Likewise. And I would love to hear your thoughts when you read A Month in the Country.

Okay, fine. I've got to read one book right now that I'm doing a review for. But after that, I will read A Month in the Country.

Okay. Awesome.

Thank you so much for your time, Sherry. This was awesome. I'm so excited.

My pleasure. Thank you so much, Russell, for your time. I really enjoyed this.

(Amazon Affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)